Dan Terrio: walking a tightrope between two worlds

"Resiliency is in my DNA. I will always persevere. My people have been through far, far worse."

On a Friday afternoon in eighth grade, Dan sat in the back seat of his family’s van, heading toward Shawano, Wisconsin for the weekly grocery run. There was nothing unusual about that day; in fact, they’d taken this same trip many, many times. They always took a country road near Morgan Siding, a place known for railroad history, although in all their years of driving that route, they had never once seen a train.

As they approached the railroad crossing, there were no lights, no gates, and no warning bells. There was nothing to indicate there was danger ahead. Dan doesn’t even remember crossing the tracks.

But he does remember the darkness.

Thanks to friends, family, and neighbors, Dan survived these aggressions to learn the true meaning of community. It was about the open door, the shared meal, the stories being told, and the common ancestral experiences of his people – good and bad.

"Resiliency is in my DNA," Dan asserts.

"I will always persevere. My people have been through far, far worse."

But resilience often comes at a cost. By ten years old, Dan was already looking for an escape from the bullying at school and a volatile situation at home. He started doing drugs to numb the feeling of being an outsider in his own life. He started cutting himself.

Then came the train.

Following the accident, Dan didn't just walk again: he ran. Taken under the wing of mentors like the late Dorothy Davids and Dr. Ruth Gudinas, pioneers in social justice, Dan channeled his trauma into advocacy.

At fourteen, he began training as a motivational speaker.

By sixteen, he was elected to the national board of UNITY (United National Indian Tribal Youth), traveling to Washington D.C., advocating for Native youth, and serving on national commissions.He became a "golden child" of sorts: a young leader articulating the pain and hope of his generation. But, underneath it all, the fracture in his sense of self was widening.

For nearly two decades, Dan Terrio lived a double life.

Publicly, he was the Youth Development Manager for the Green Bay Chamber of Commerce, a rising star overseeing leadership programs for seventeen area high schools. He was the man officiating weddings, writing grants, and shaking hands with politicians. He was a success story.

Privately, he was a ghost in his own city.

"He said, 'Dan, you have always been Two-Spirit, and being Two-Spirit is a gift from the Creator. It is reserved for someone born with both masculine and feminine energies. Our tribal elders have always known this about you.’”

His father broke it down: Dan had been a warrior for youth in Washington D.C., fighting for their rights in the halls of power. This was traditionally a masculine role. Yet, he had also been a nurturer, a caregiver, a "father figure" to countless young people who had none. This was traditionally a feminine role.

"He told me, ‘You’ve always embodied the life of a Two-Spirit person, but you had to realize it and discover it for yourself.'"

"I’m going to reward you," he imagines the universe told him that long-ago day on the beach.

And as he sits in his office in Milwaukee, fully seen, fully himself, and fully out, it seems the universe kept its promise.

We are proud to have Dan Terrio serve on the Board of Directors of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project.

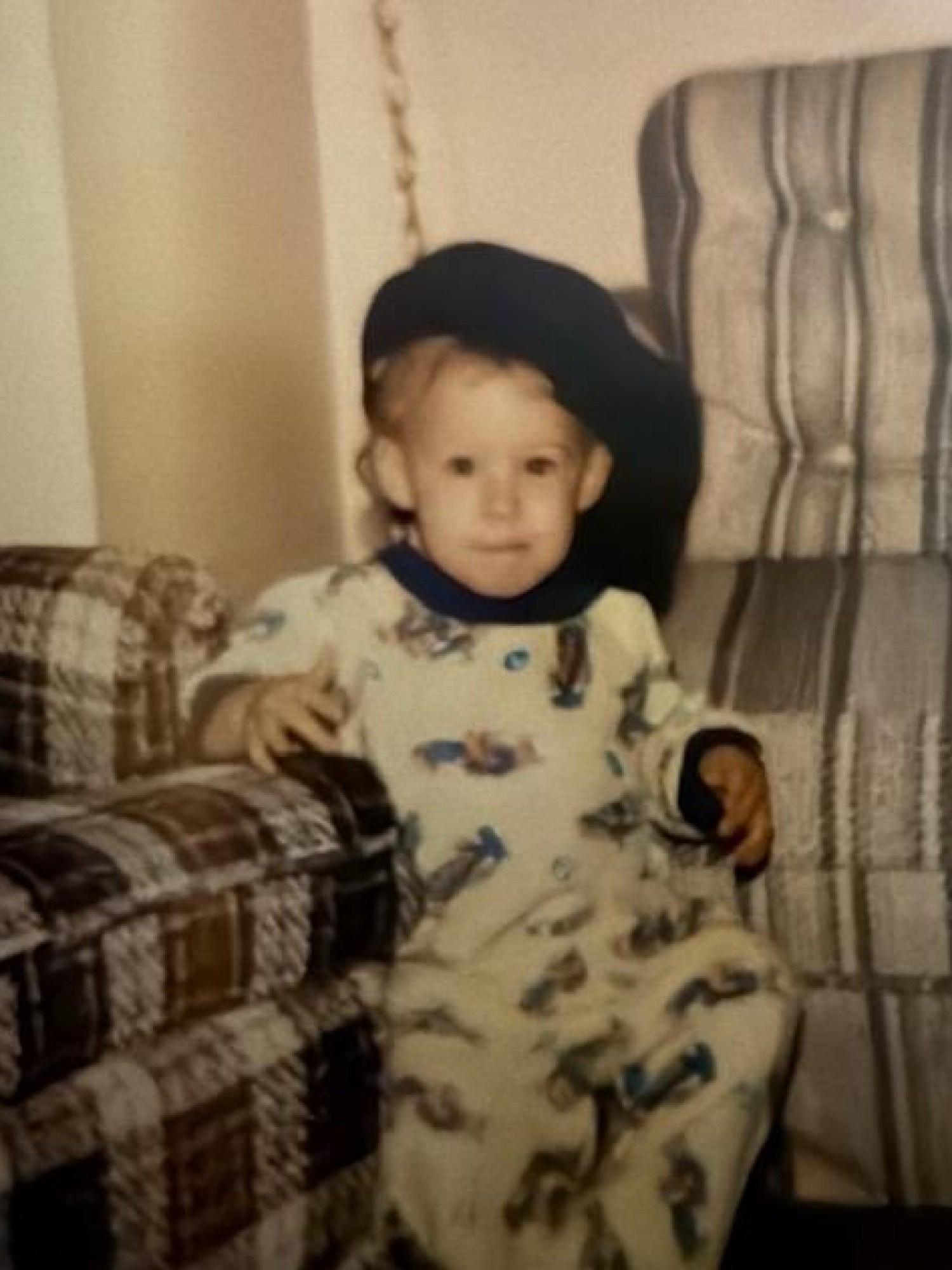

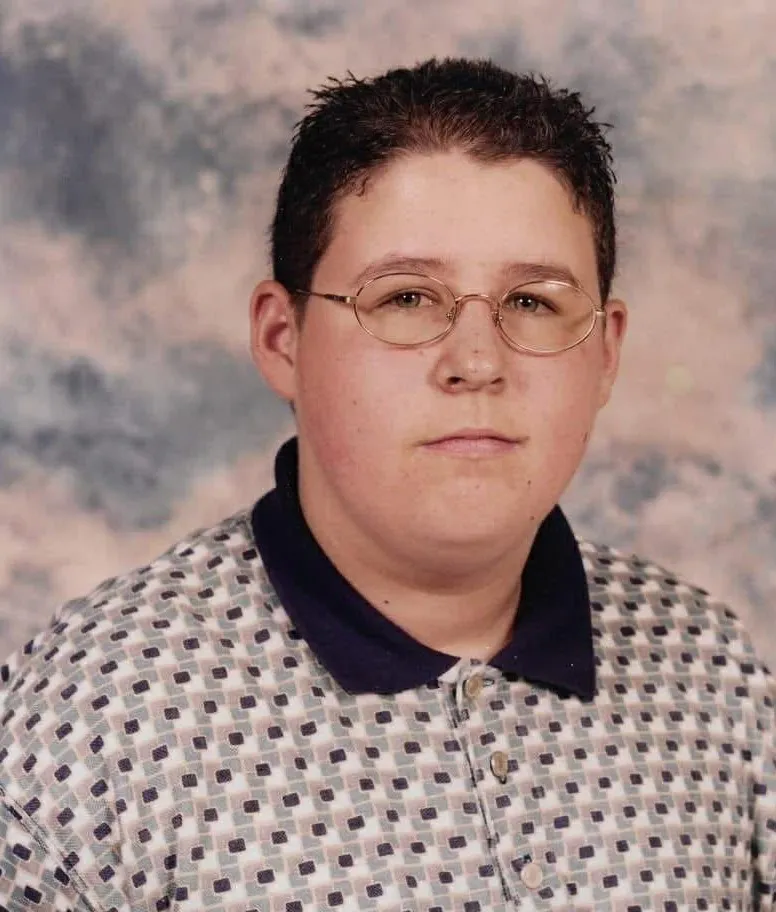

Dan Terrio

Dan Terrio

recent blog posts

February 25, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 24, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 21, 2026 | Meghan Parsche

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.