Debbie McCarty: creating a sanctuary in the shadows

“In the end, our freedom was more expensive than I thought.”

For a young woman in the 1980s, north central Wisconsin felt vastly different than it does today. Secrecy was not a choice; it was a necessary shield. Yet, in the heart of Wausau, a handful of small, downtown bars offered a rare flicker of light. It was in this environment that Debbie McCarty would defy convention, claim her identity, and ultimately become a pioneer, carving out a vital, temporary refuge that drew LGBTQ people from hundreds of miles away.

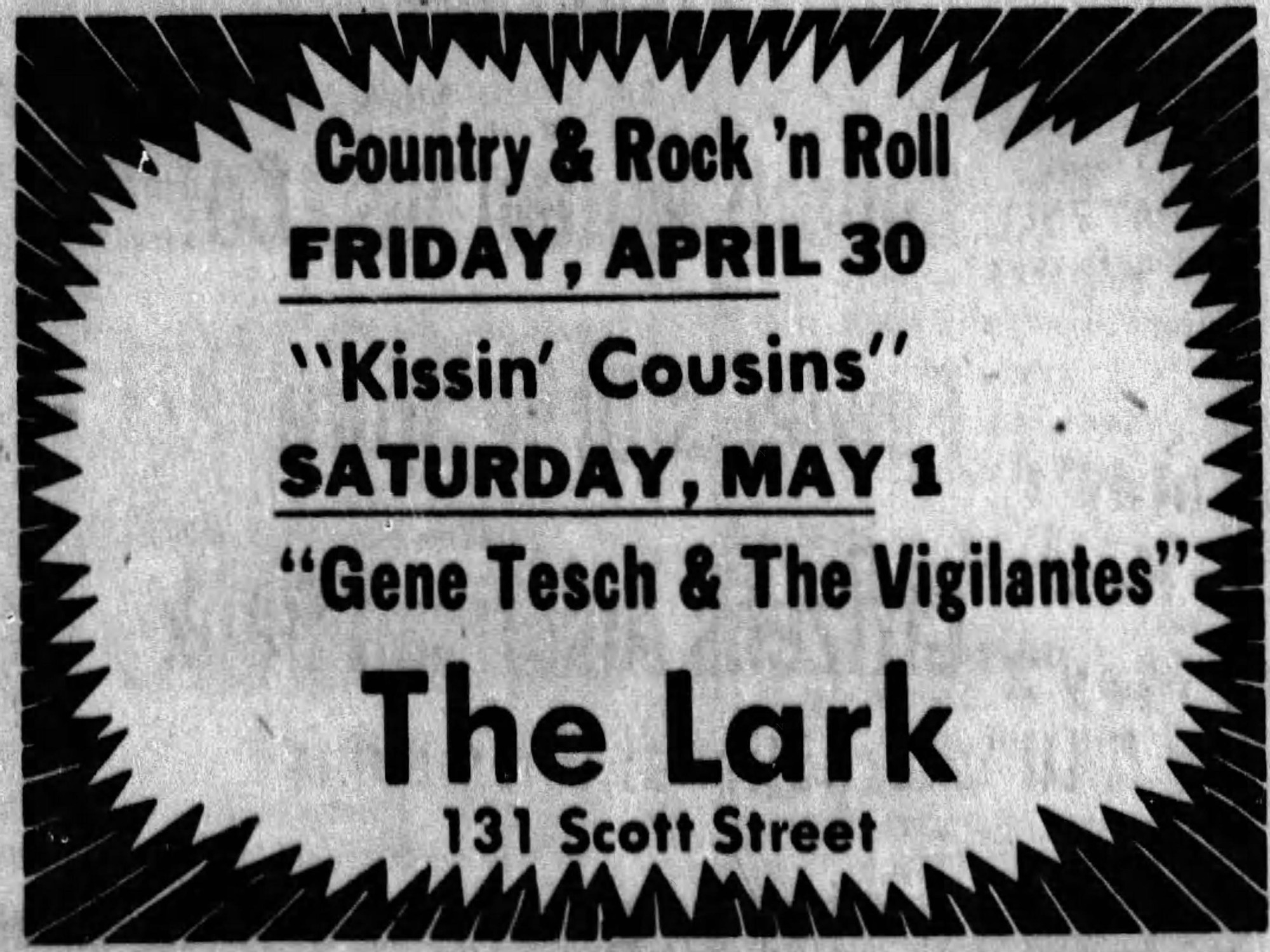

McCarty’s journey began with an act of defiance. Growing up, she always knew she was different but didn’t know what her feelings meant. When she turned eighteen, she decided to go out and celebrate. Her brother, Wayne, who lived in Wausau, had given her a clear, stern warning: “Whatever you do, don’t go to The Lark or The Pit.”

“So, on my 18th birthday, that was exactly what I did,” McCarty recalls. “The first bar I ever went to was The Pit.”

Curtis Charbonneau finally sold in 1981, first to Brenda Lee Jahnke and then James Zahn. According to city records, it was vacant for a short time before Bill Mathiesen reopened as The Lark in 1983.

And now, Debbie was continuing the tradition.

She started commuting back and forth between Stevens Point and Wausau daily. She restructured the bar operation, trained the staff, and poured her energy and expertise into turning around the business. It wasn't long before she realized it was working.

“It just got to the point where I was putting in so much time…. I finally said, you know what? I want part ownership.”

Since The Pit had closed in 1982, it was even more important than ever to Debbie that Wausau have a space for queer people than ever. The bar was long known as a place where “gay people hung out,” but under McCarty’s guidance, it transformed from a secret rendezvous point into a regional center for LGBTQ life. She had a singular vision that transcended mere business: to create a place where people could be themselves and where anyone felt comfortable.

The atmosphere was welcoming, and the clientele grew quickly, seeking an oasis from the isolation of their smaller, surrounding communities.

“A lot of gay people were coming to The Lark, and it gave me a bright idea,” laughed Debbie. “But looking back, maybe it wasn’t so bright.”

“People would say, you know, faggot this and faggot that.” Gay men were subjected not only to verbal assaults and intimidation, but people would physically harass them. Debbie remembers people trying to trip men as they walked through the bar.

“It was really immature behavior,” she said, “and it really pissed me off. You better believe I spoke up.”

Debbie was also the victim of homophobic violence. She vividly recalls being attacked by three straight women who accused her of making a pass. (She didn’t.)

“They jumped me, held me down, and kicked me in the stomach,” said Debbie. “They fractured my ribs, and I had to recover at my father’s house, sleeping on the floor because I couldn’t sleep in a bed.”

Debbie was always very cautious about her customers safety. Since The Lark was located at a highly visible downtown intersection with a stoplight, the fear of being outed was real.

“There was a really big fear of being seen,” said Debbie. “Yeah, the Lark could be an escape from the outside world, but the outside world was still out there waiting for you. Yes, there were places we could go, but it wasn’t exactly a paradise.”

“We had a back door that led to the parking lot, so people could enter without being seen by traffic,” she says. “However, it was dark out there, and you never knew if someone was lurking in the shadows. I always warned people to be very, very careful.”

Debbie didn’t live on the premises, so closing the bar alone at night was sometimes a little spooky.

Customers developed clandestine methods to protect their safety, careers and reputations.

“There was a lot of sneaking in. They waited until all the cars passed before they would enter the bar. If cars were stopped at the intersection, they’d just keep on walking right past The Lark, and then double back when the coast was clear.’

“I had a lot of people tell me that over the years,” she said. “Isn’t it funny to think about now?”

“Looking back, the drag shows weren’t really the smartest thing I could have done, financially, even though it was very important to me personally,” said Debbie. “I wanted to create a place where everyone felt comfortable and everyone could be themselves. In the end, I guess that freedom was more expensive than I thought.”

She was lost in thought, remembering the fun, the community, and the fear of that little corner bar—so lost, in fact, that the driver behind her honked several times to bring her back to reality.

"I just sat there for awhile," she said. “I was lost in La La Land, thinking about all the fun that we had."

"And that’s how I remember The Lark. I don’t think about the bad times, I don’t think about the scary times. I just remember all the fun times.”

The Lark won't just be remembered as a bar, but as a moment of courage. It might have been a temporary haven, a brightly lit stage in a dimly lit time in Wisconsin history, but it was also a transformative moment in Wausau’s growth. It was a courageous endeavor by a woman who chose to build a community even when the world told her she shouldn't.

By defying expectations, in nearly every chapter of her remarkable life, Debbie McCarty made Wisconsin history.

Debbie McCarty, 2025

Debbie McCarty, 2025

recent blog posts

February 24, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 21, 2026 | Meghan Parsche

February 14, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.