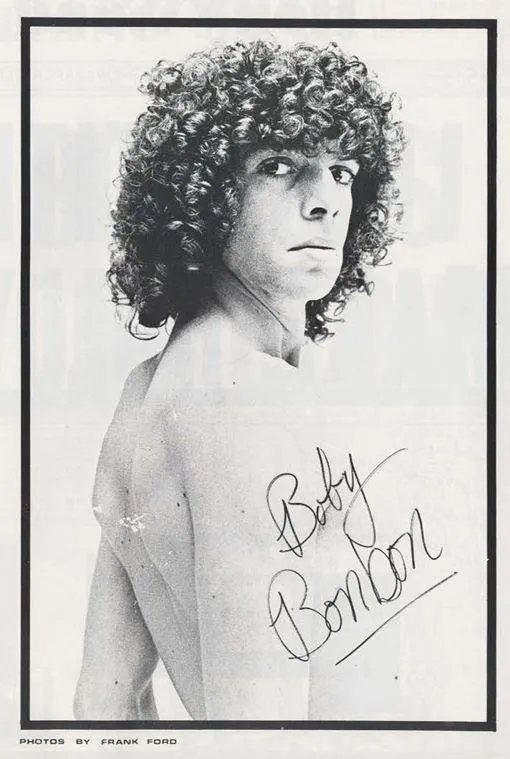

In memoriam: Francis "Frank" Ford (1945-2025)

"Go out and photograph the world."

Within the streets of Milwaukee, amidst the hum of factories, the strange beauty of decaying warehouses, and the humble streets of working-class neighborhoods, Francis “Frank” Ford found a secret universe of mystery and awe.

Ford, who passed away on Sunday, December 14 at the age of 80, was not merely an observer of his hometown. He was its visual historian, a man revered as “the city’s house photographer.” Ford’s career was a testament to the belief that art is not created in a vacuum, but discovered in the organic, often chaotic, energy of human connections.

“This is truly a loss,” said Peter Mortensen. “Francis documented a Milwaukee that is rapidly moving towards the mythical.”

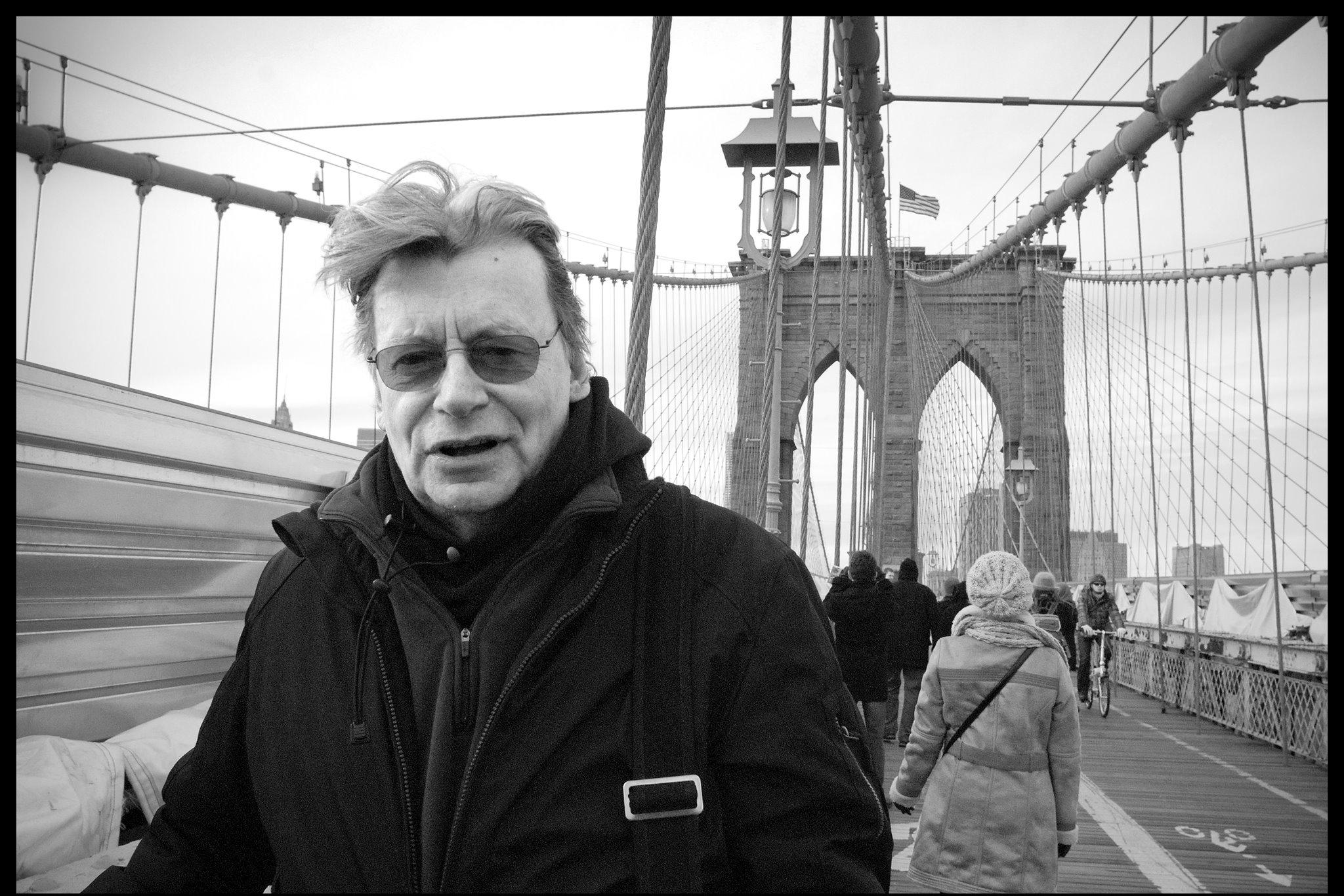

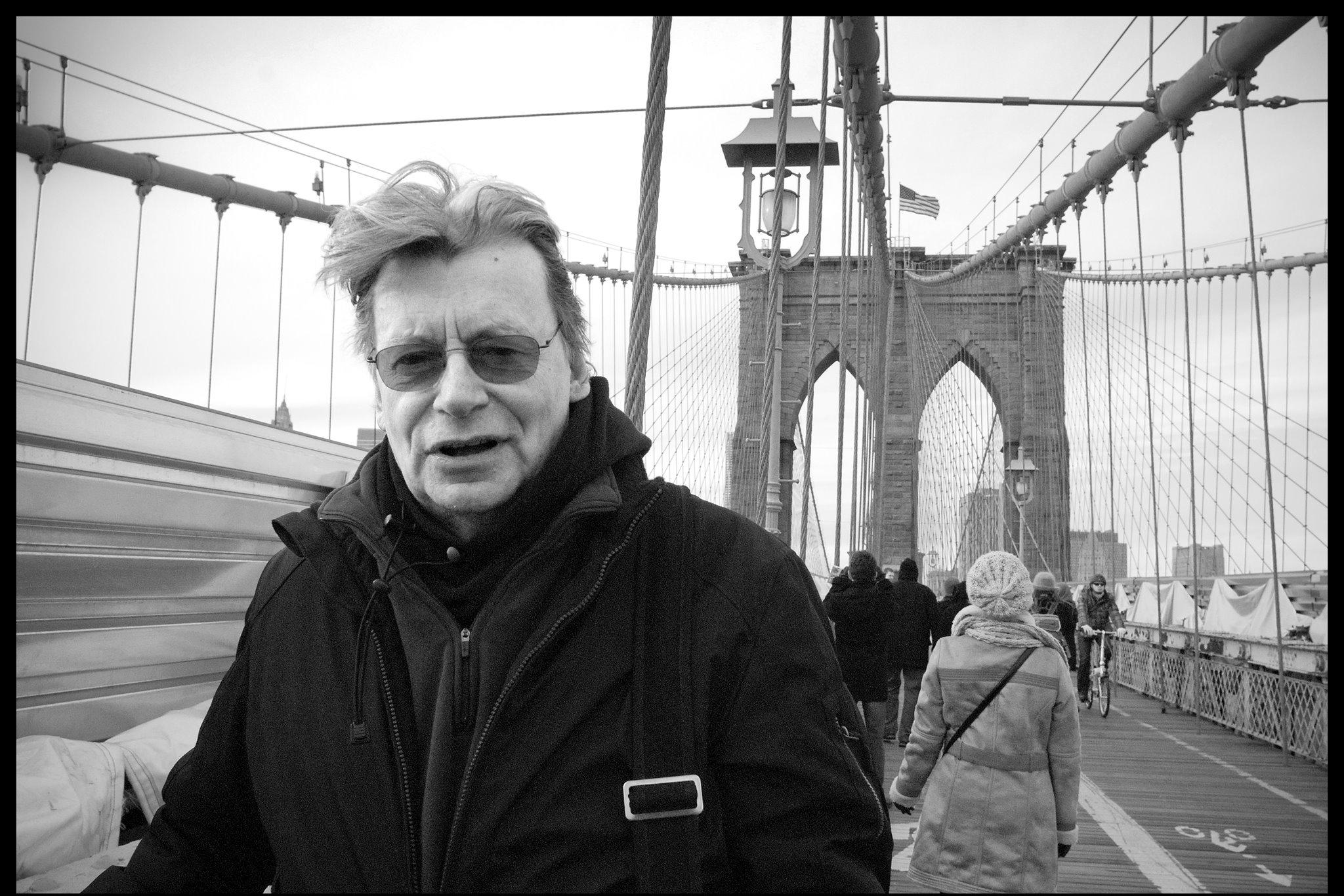

Despite his commercial success, Ford remained devoted to street photography. He never prioritized making "big money," preferring the authenticity of capturing the world as it was. This authenticity drew the admiration of his peers and subjects alike. When the legendary photographer Richard Avedon expressed a desire to buy a photo Ford had taken of him, Ford was stunned.

“I was blown away,” Ford stated, calling it one of the best moments of his life.

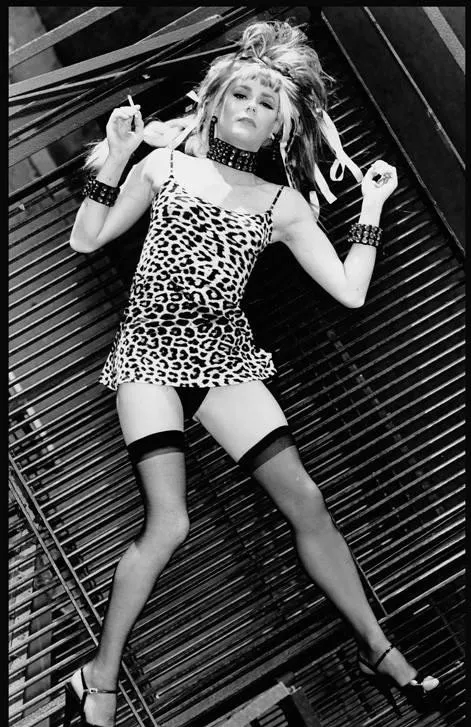

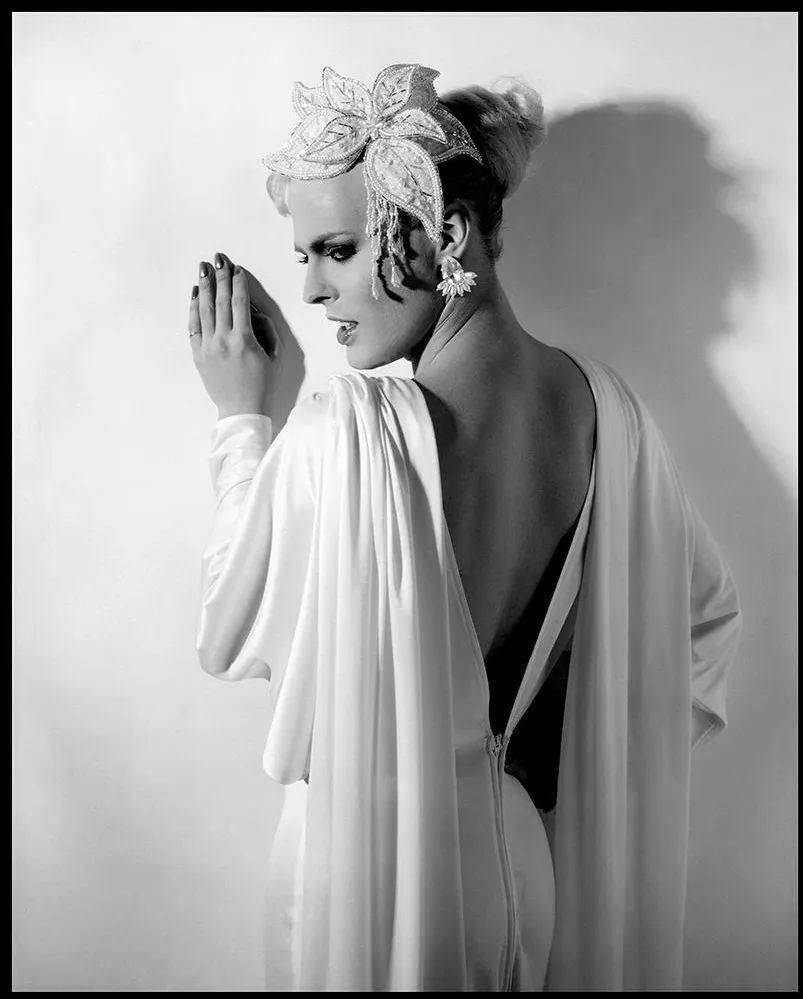

Ford immersed himself in the 1980s drag community for years and developed deep friendships. He saw a profound connection between the performers, a love that bound them together in “a whole another world.” He drove a station wagon, which he would pile with four or five drag queens to crash parties across town.

“People didn’t know us at all, and here’s this drag parade coming in,” Ford said. While people often had preconceived notions about drag, Ford noted that by the time the party was over, they “were always rocking out with the queens.”

“He shot my cover photo from the Miss Continental program the year I gave up the crown,” remembered legendary drag performer Mimi Marks. “He was such an awesome man. He built a whole set for me to lay on. I remember being in the studio, and it was so hot that my hair wouldn’t keep a curl.”

Reflecting on the evolution of the art form, Ford marveled at the cost and complexity of modern drag.

“I can’t imagine a group of queens with these thousand-dollar outfits back then,” he said. “How are these girls affording this stuff?”

He noted that drag has helped people in the “hinterlands” understand the art form, reduce anti-gay sentiment, and accept gender diversity. At the same time, he felt that drag has lost some of its bite in recent years, with more of a focus on fame than flavor.

“It’s such a performance that you’re not even sure it’s human anymore,” said Ford. “The best drag is based in enchantment, in wonder, in momentary joy.”

Holly Brown

Holly Brown

Miss B.J. Daniels

Miss B.J. Daniels

Mimi Marks

Mimi Marks

Beyond his work as a photographer, Ford was a beloved educator. He taught at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design (MIAD) starting in 1992, as well as teaching at a Milwaukee language immersion school. His mandate to his students was “go out and photograph the world”.

Those who knew him personally remember a man of dualities. B.J. Daniels described Ford as a “very funny guy, goofy even,” who would transform the moment he picked up a camera.

“He was all business when it came to crafting imagery,” Daniels recalled. “His lighting was painstaking, and his poses were deliberately constructed to capture that light perfectly.”

Daniels, who met Ford in 1983 at George’s Vintage Clothing, remembered Ford coming in with his girlfriend, artist Carri Skozcek, looking for a wedding dress—for Ford. It was typical of Ford’s humor and disregard for convention.

Ford’s later years were marked by health challenges. In 2010, he suffered a major heart attack and a near-death experience, surviving despite a grim prognosis. He continued to be a presence in the city’s arts scene until his death.

Tributes to Ford emphasize the "mystery and awe" he captured in his subjects, whether they were famous actors or his neighbors in Walker’s Point. John Shiman and Julie Lindemann, writing in Art Muscle, noted that Ford’s fandom of personalities—both famous and obscure—infused his pictures with a “bigger-than-life quality”.

Francis Ford leaves behind a legacy preserved in the Art Muscle digital collections at the UWM Archives and in the memories of the students whose lives he changed forever. He was a friend who always had a kind word, a teacher who shared his insight freely, and an artist who saw the extraordinary in the ordinary.

As B.J. Daniels summarized, “His eye and his lighting were the best of the best... There will never be another like him. The photos we did together will always keep his memory alive.”

In a life dedicated to capturing everyone’s best light, Francis Ford ensured that the vibrant, messy, and beautiful faces of his city would never fade into the dark.

We were proud to interview Francis Ford on January 13, 2024, and tour his photo collection later that month.

Rest in peace, Mr. Ford.

recent blog posts

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 10, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.