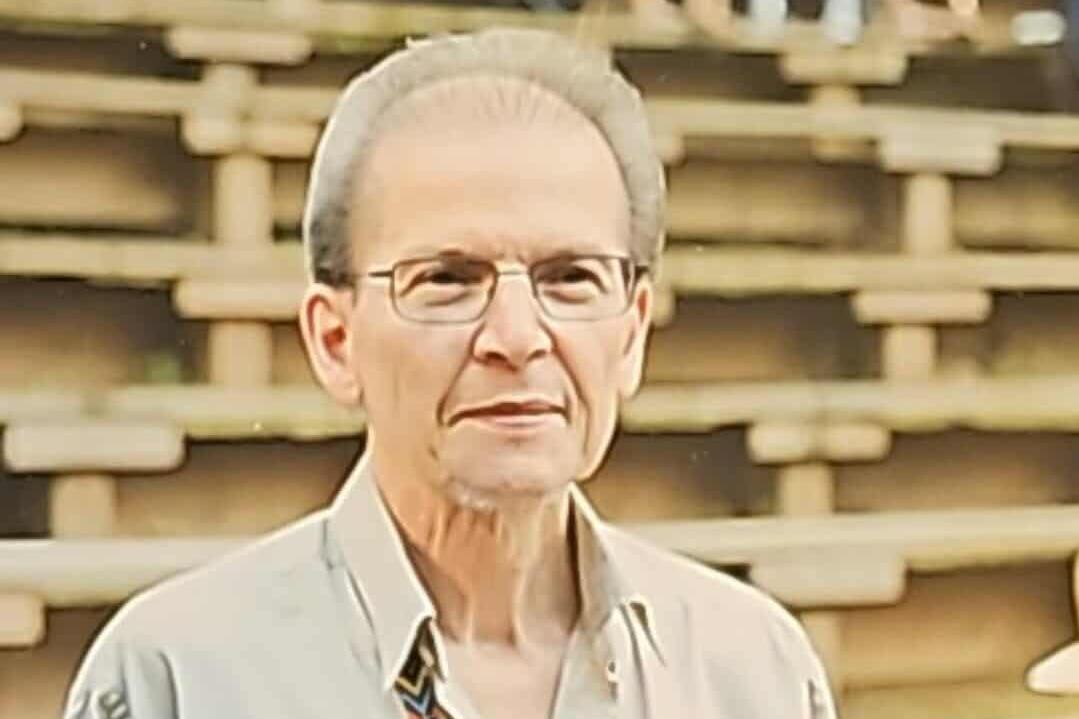

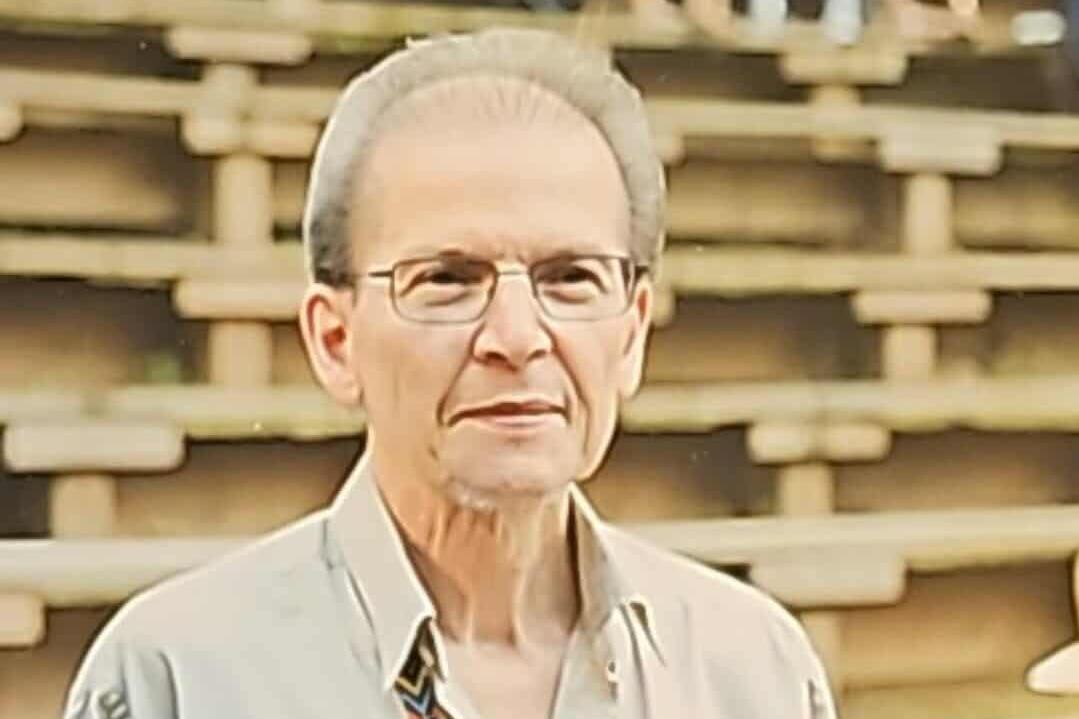

Jim La Rock: caretaker, catalyst, and Menominee Historian

“Two Spirit life means living both male and female lives in harmony,” said Jim.

“You are a caretaker, a healer, an advice-giver, a source of heritage and culture, a keeper of traditions, but also someone who creates and maintains spaces where others feel deeply, truly cared for.”

The sound of the drum and the chatter of the pow wow fade into the calm, peaceful warmth of Jim La Rock’s home in Keshena, Wisconsin.

At 75, Jim is a study in quiet dignity, his life a rich tapestry of profound loss, unexpected freedom, and hard-won respect. For decades, he was known for being the first male high school secretary, the man who brought house music to the office, and the tough-but-fair mentor who proudly applauded as hundreds of Menominee children walked across the graduation stage.

Today, however, he is known simply as The Menominee Historian, a title earned not through a degree, but through the singular, relentless act of memory: sharing the intimate, often forgotten, history of his people on social media.

Jim’s life is a masterclass in radical reinvention. He was a survivor of childhood tragedy, a target of homophobic bullying in the 1960s, an underground marijuana source in the 1970s, a pillar of the school system in the 1980s, and a man who finally claimed his full identity as a Two Spirit elder in his later years. His story is a powerful testament to the idea that self-acceptance is the only true form of freedom.

“I am who I am,” Jim says simply, his gaze steady. “And they can accept that, or they can deny it. But they can’t change me. Never.”

“I was considered the top seller in the area,” he notes, providing a pack of papers and matches as his simple calling card. People even offered to be his bodyguards.

For three years, Jim led a double life, a respected shift manager by day, and a weed dealer by night.

Karma caught up with Jim in a most unexpected time and place. One afternoon, he was sitting with a friend at his dining room table when a car pulled up and five large men got out.

He immediately recognized them: the same guys who had relentlessly harassed him years earlier, the ones he used to hide from in the woods?

They were at his front door. What did they want?

“I heard you have good stuff,” the man said. “Can I buy some?”

Jim invited them inside. They sat, fired up joints, and listened to music. The irony was thick and silent. Jim didn't know how to approach them, and they didn't know how to approach him. The terror of the past had vanished, replaced by an uneasy mutual respect.

The power dynamic had definitely reversed.

His cassette tapes weren't typical office fare; they were recordings of WIXX-FM on-air dance parties, featuring cutting-edge Chicago house music remixes.

The office quickly became an unofficial youth center.

“Kids would come and listen to my music and relax -- and then go on their way,” Jim says.

They saw him as different but respected his differences. His identity wasn't a secret he had to hide. It was part of his character.

His commitment to this new role was absolute. In 1984, he stopped smoking and drinking.

“I couldn’t preach something to kids I was doing myself,” he explains.

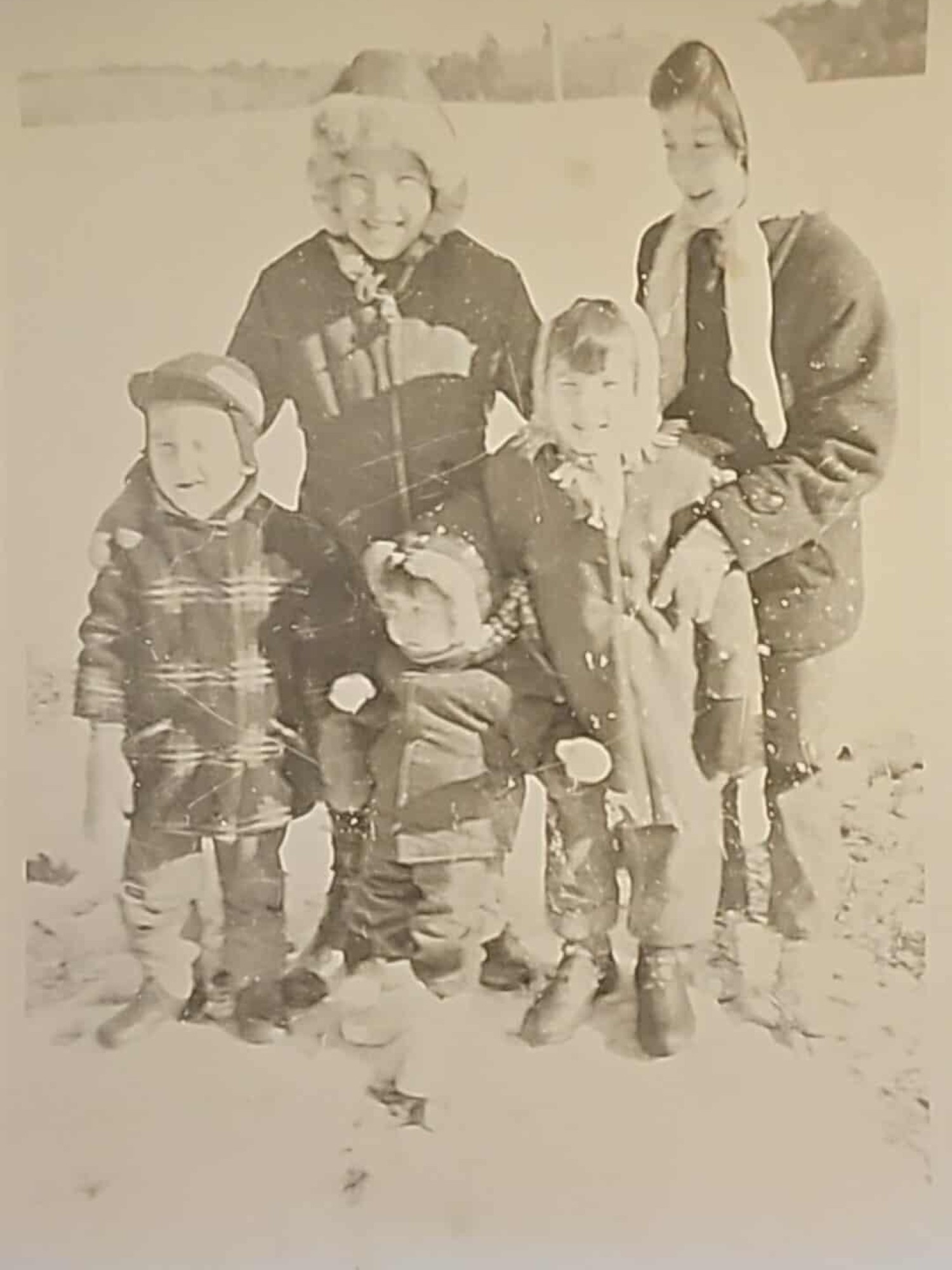

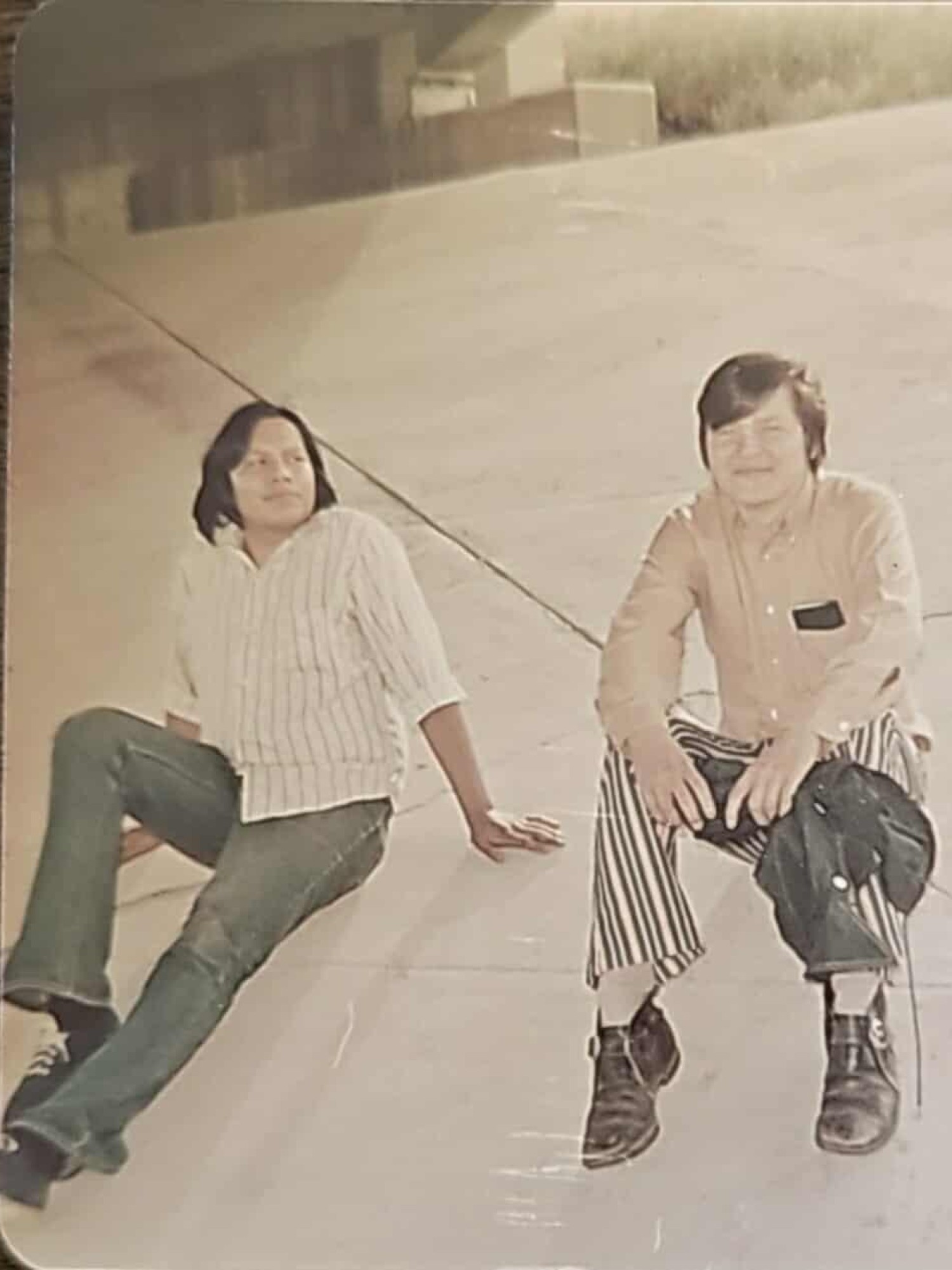

Jim (left) and friends Karen, Carmen and David, 1975

Jim (left) and friends Karen, Carmen and David, 1975

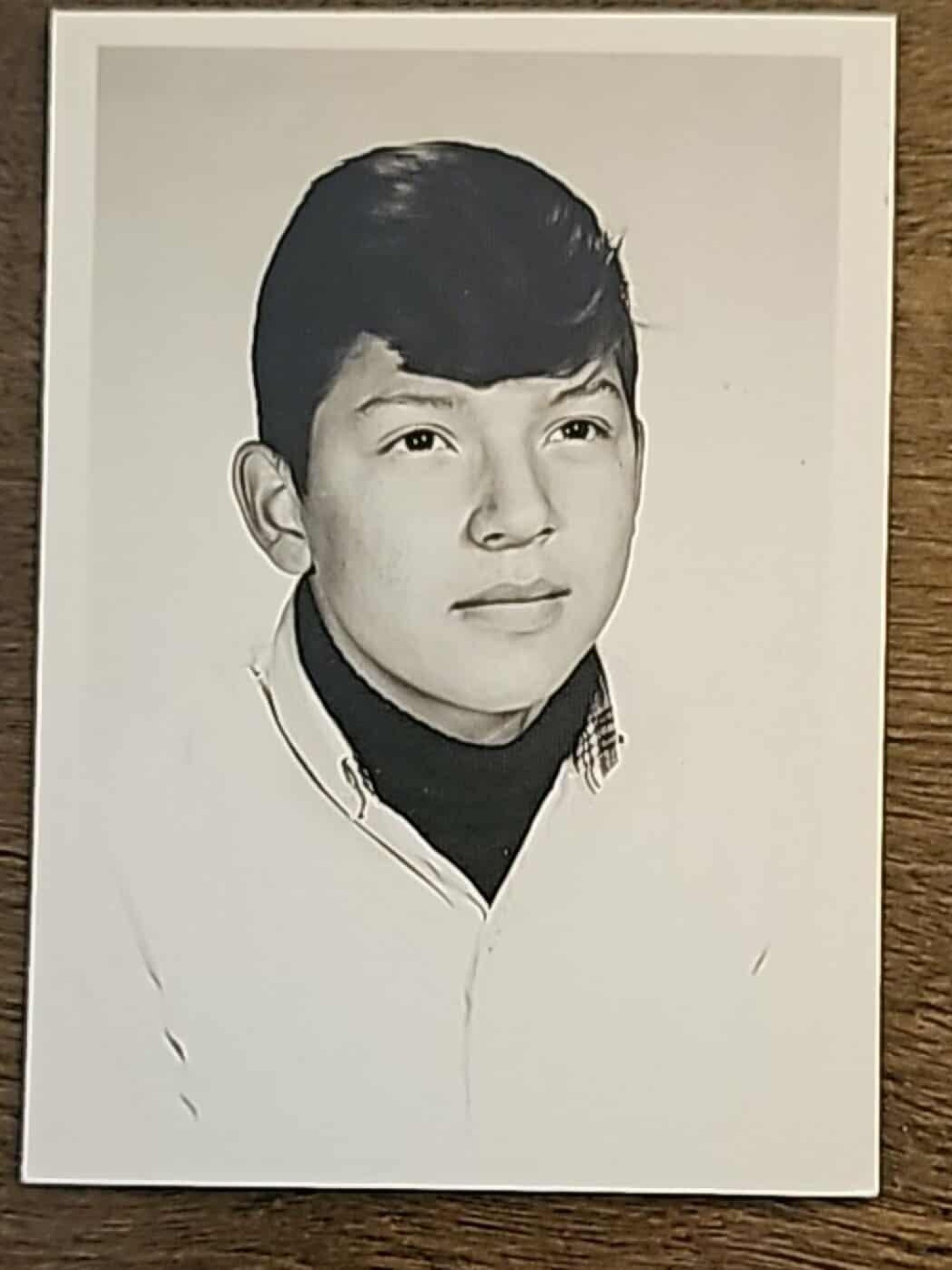

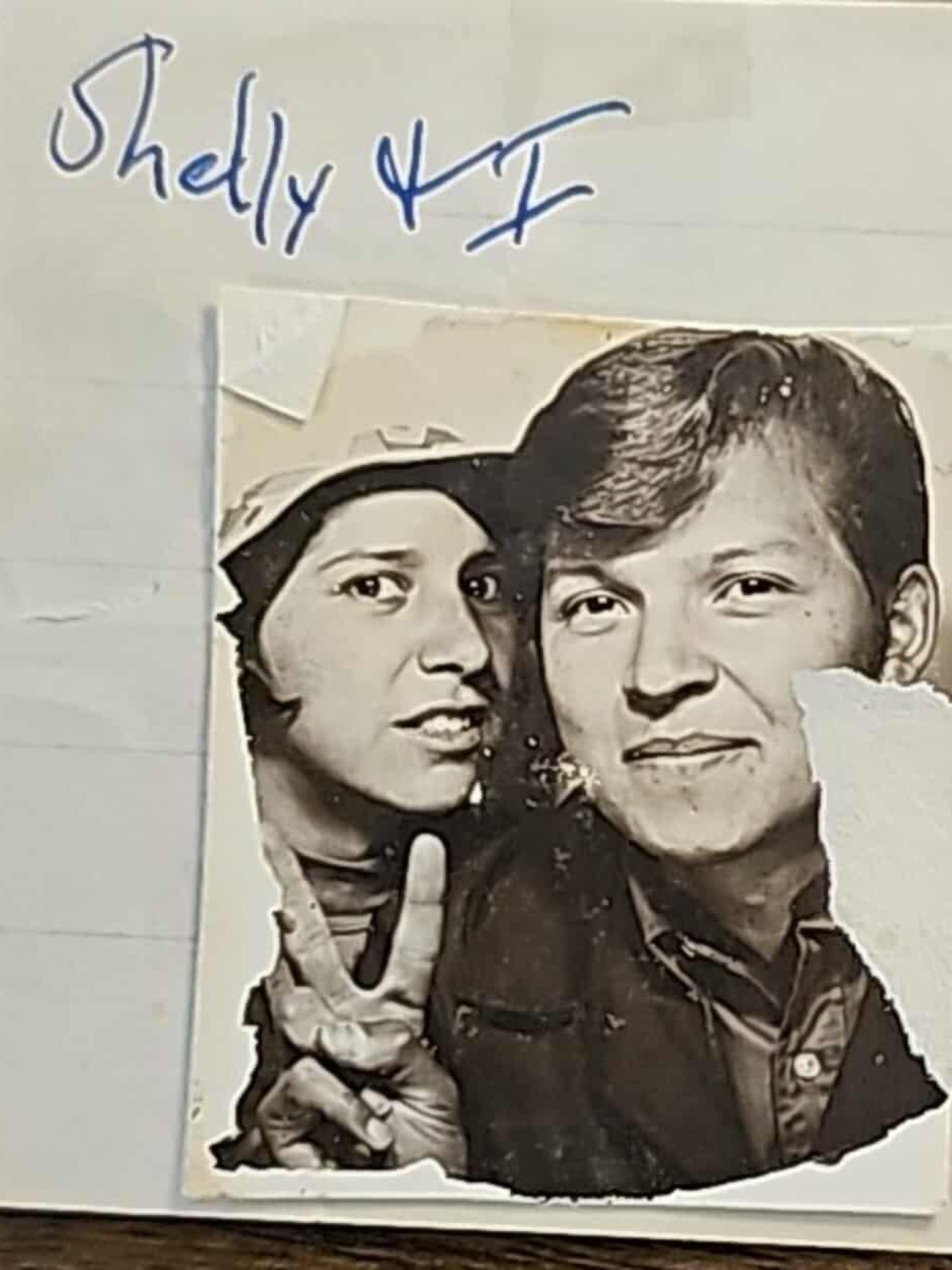

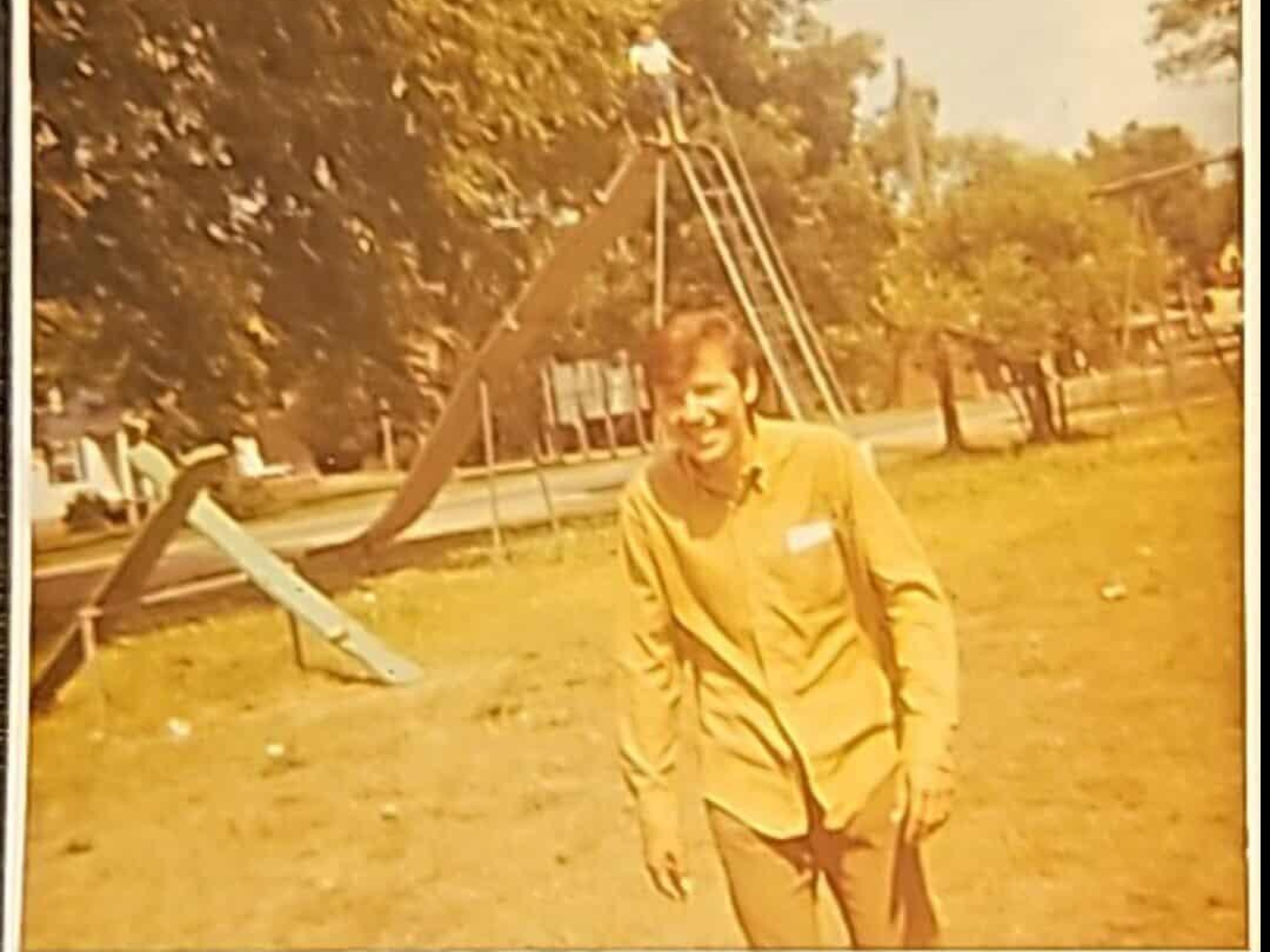

Jim modeling Sun-In hair lightener, 1970

Jim modeling Sun-In hair lightener, 1970

He became a silent guardian angel, helping pay for class pictures, donating money for field trips, and providing advice and guidance that steered them toward graduation. Ultimately, he served the school district for 23 years.

“Seeing the kids go across the stage was the biggest accomplishment I could claim,” Jim says, his voice full of pride.

Graduates would often return, thanking the man who was often a “hard ass,” but whose firm hand and care meant everything. He gave them the guarantee that someone believed in them.

When technology swept through the office, Jim, at 57, decided to retire rather than commit to two more years of vocational school. He was already preparing for his next chapter.

Answering a higher calling

After years of driving back and forth to work at Oneida Bingo, Jim achieved a milestone he had waited 46 years for: in 1996, he moved into his first place all by himself in Green Bay.

“I got the keys, I sat down, and I realized something: I finally had my own place,” he remembers. “It was really overwhelming.”

His final advice is a summation of his entire, winding journey—from the harassed teenager to the esteemed elder. It is the lesson learned from tragedy, from the anonymity of the city, from the pride of the dance floor, and the purpose of the classroom:

“Look around—look at who each person is—and then look at yourself. Look to see who you are. How you want to be, how you want to live your life. Don’t live for anyone else. Live your life the way you want to be. Emotionally, mentally, physically, live the life the way you want to be.”

Jim La Rock, the historian, the Two Spirit elder, the quiet mentor, represents the living history of the Menominee people -- a man who experienced tremendous losses, only to spend the rest of his life building a local legacy of knowledge, reverence and heritage.

“Going through life day by day, decade by decade, one never realizes what one experienced and accomplished,’ said Jim.

“I want to say Wae Wae Wen (thank you, in Menominee) for allowing me to share the story of my life.”

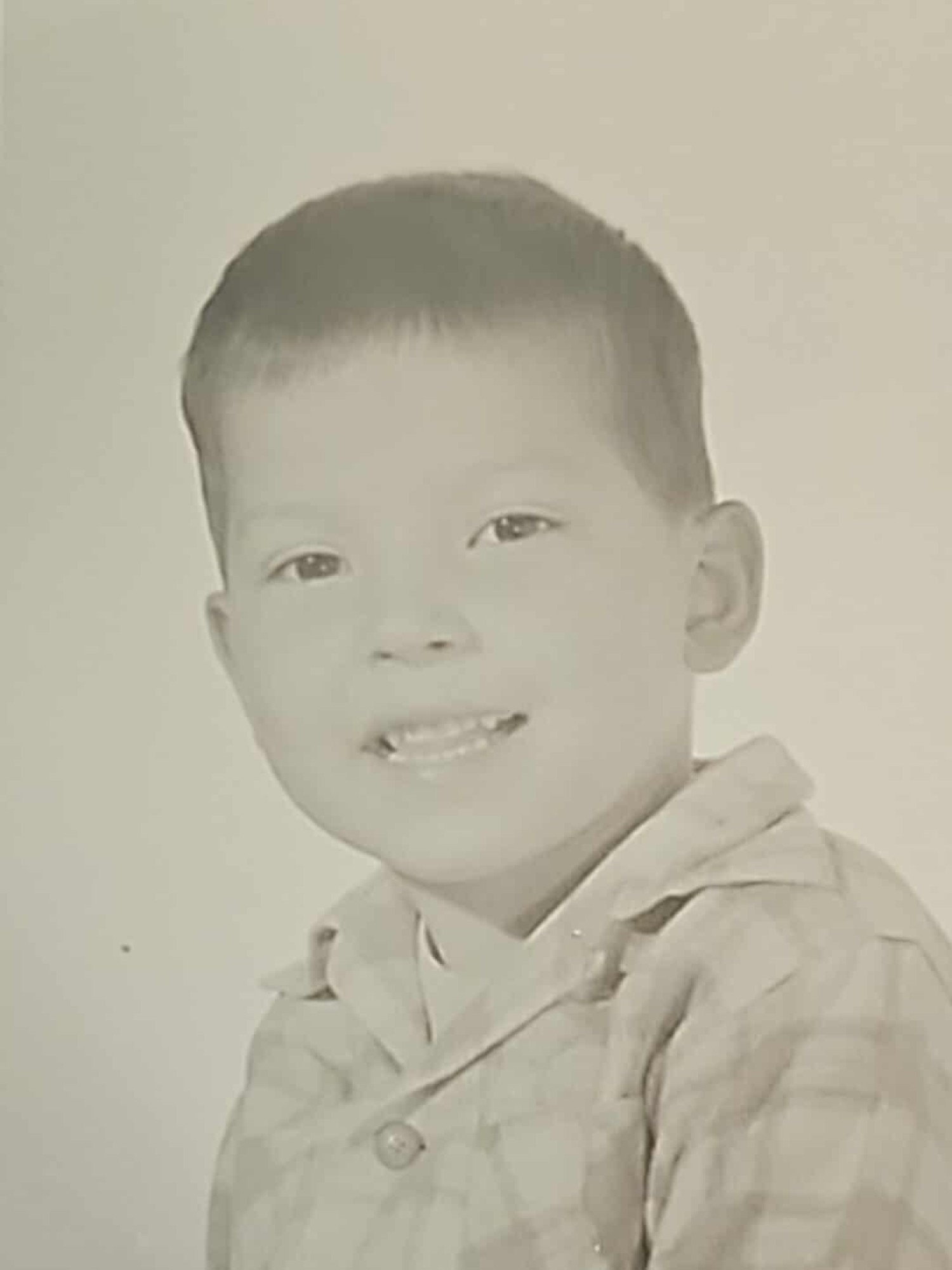

Jim and Aunt Honey

Jim and Aunt Honey

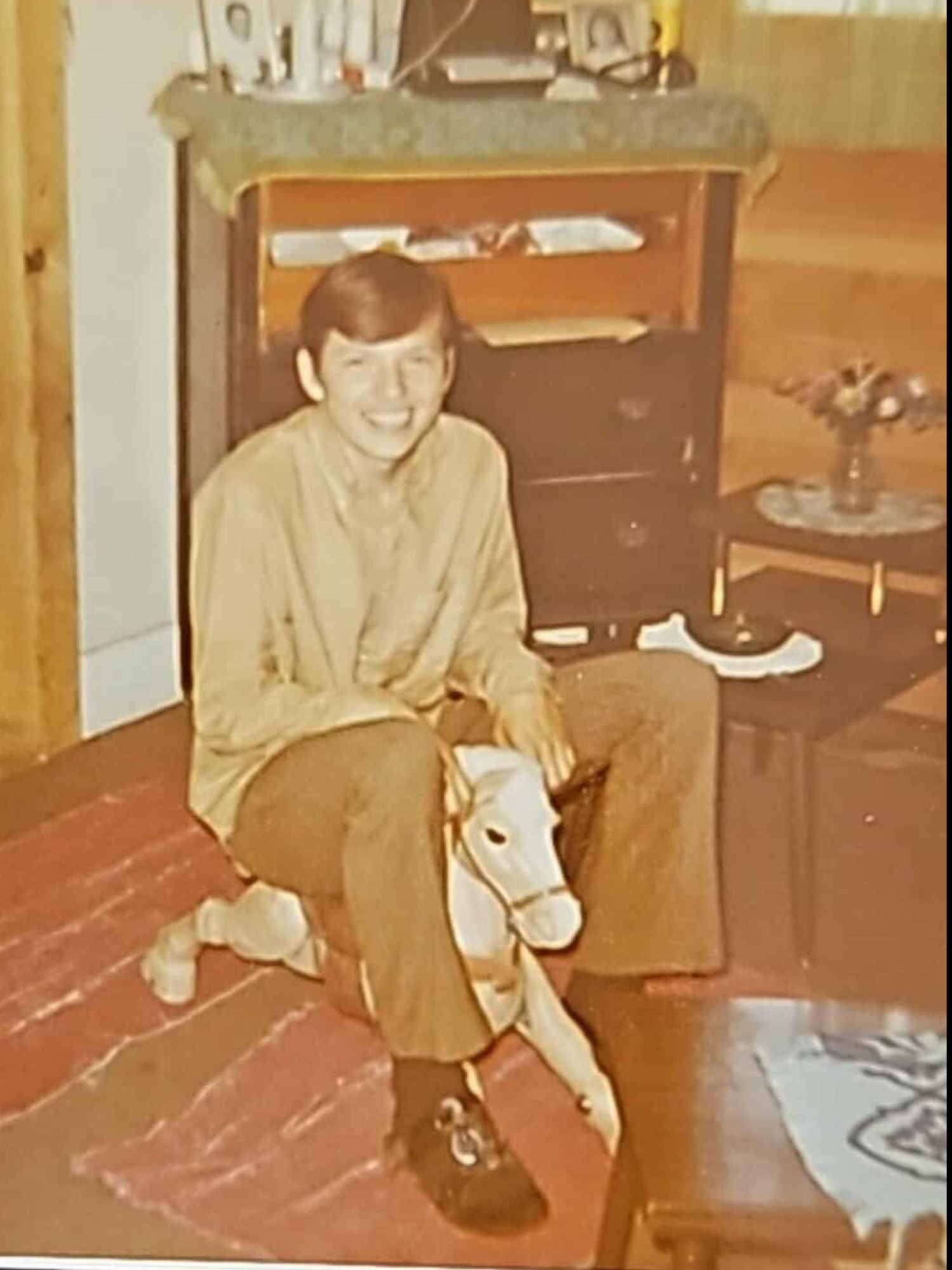

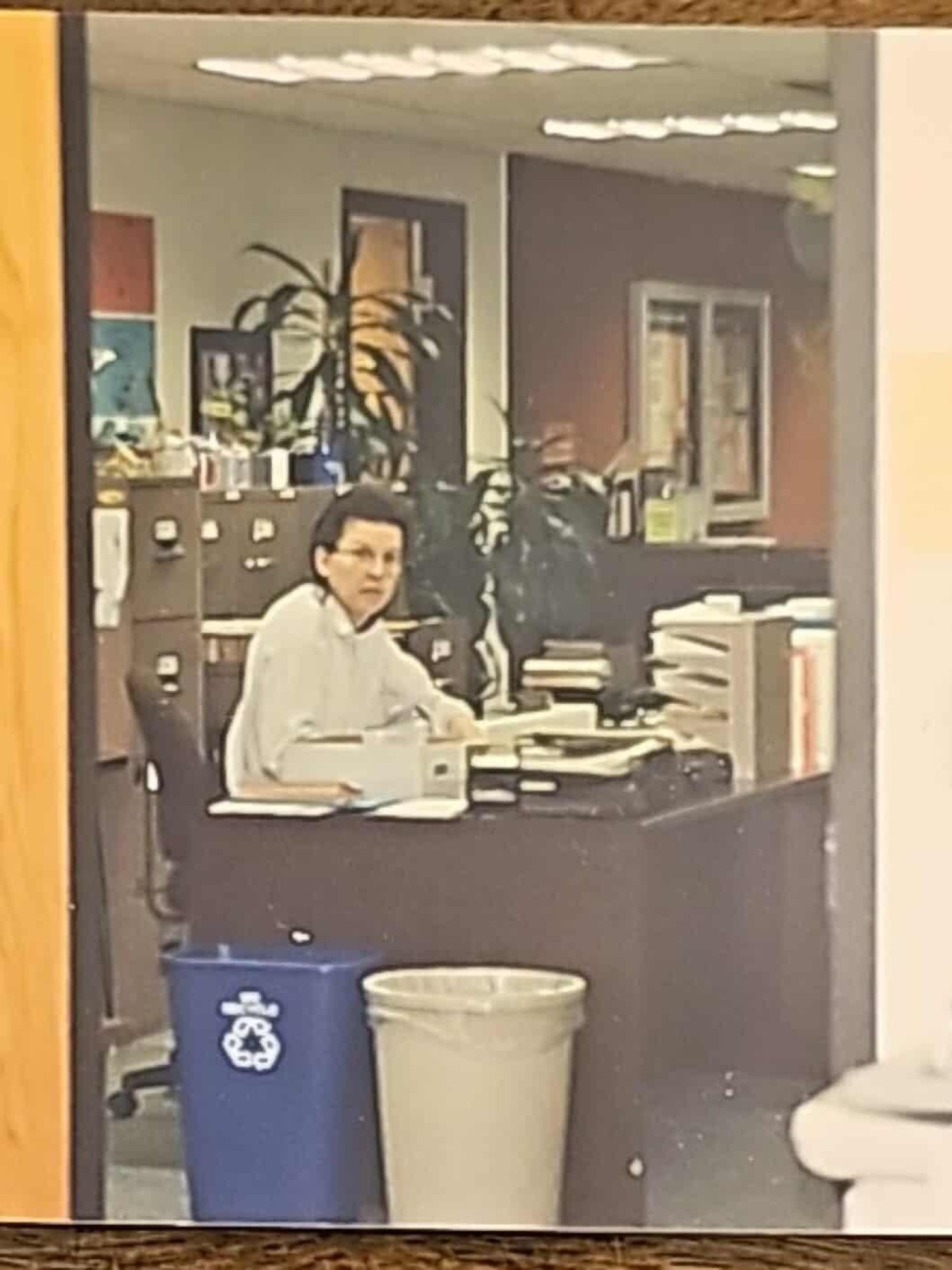

Jim and co-workers at Menominee Indian High School, 1990

Jim and co-workers at Menominee Indian High School, 1990

recent blog posts

February 14, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.