Judy Greenspan: a lifetime of truth, justice, and liberation

"Together, we were able to light a fire, and I hope that that fire continues to burn."

Going against the grain is something Judy Greenspan has always done. Sticking to their beliefs throughout the years, Judy champions rights for all and demonstrates that through their continued advocacy work in prisons, schools and anywhere else they see a need.

“I would say social justice movements. I'd say queer movements. I'm always compelled to do what other people are not doing, it's sort of like what needs to be done. What's an issue that impacts that is oppressing, you know, is the most dire and needs to be uplifted and that's sort of what I'm drawn towards,” said Judy.

“If something is really popular, I'm not there.”

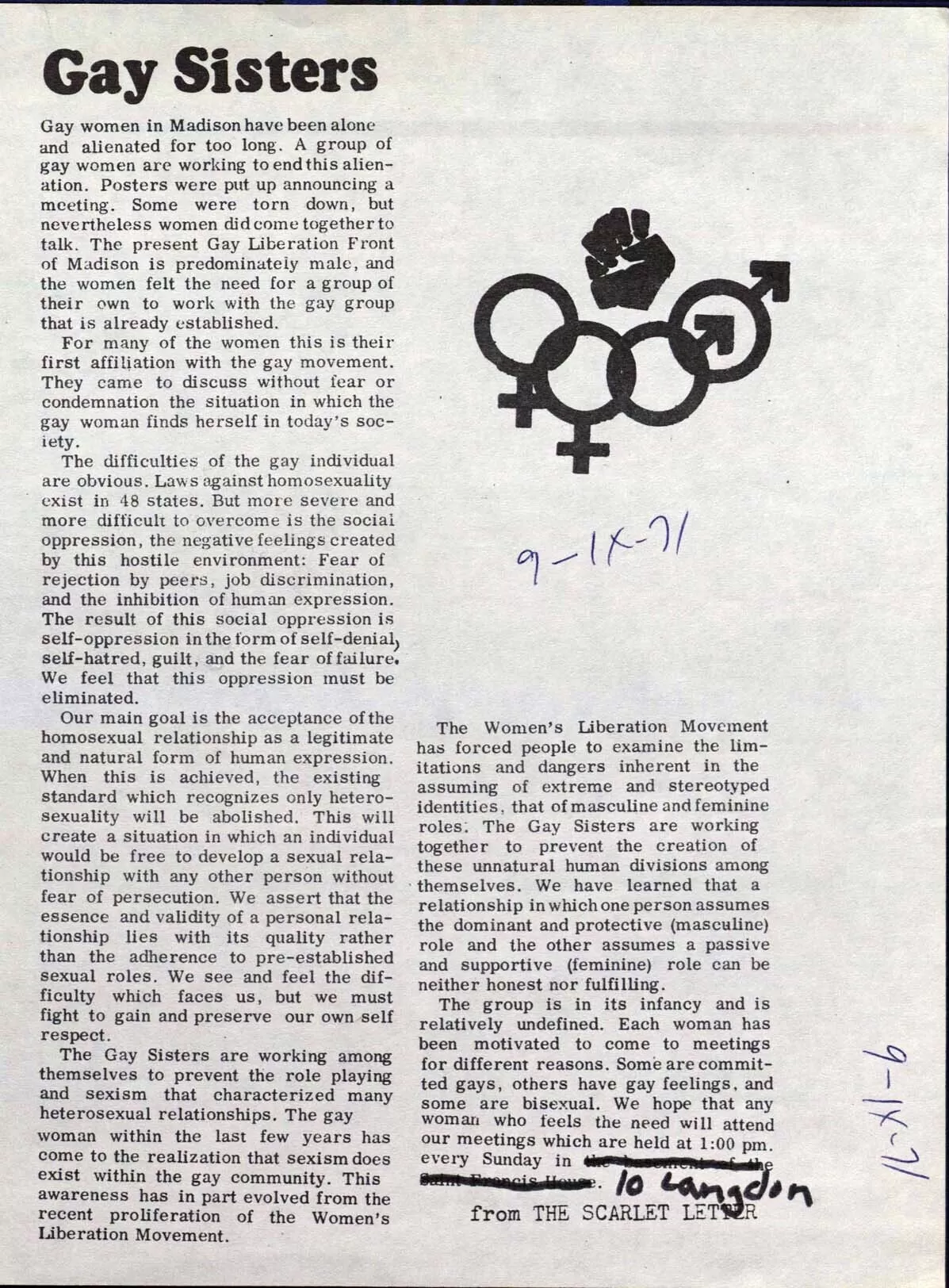

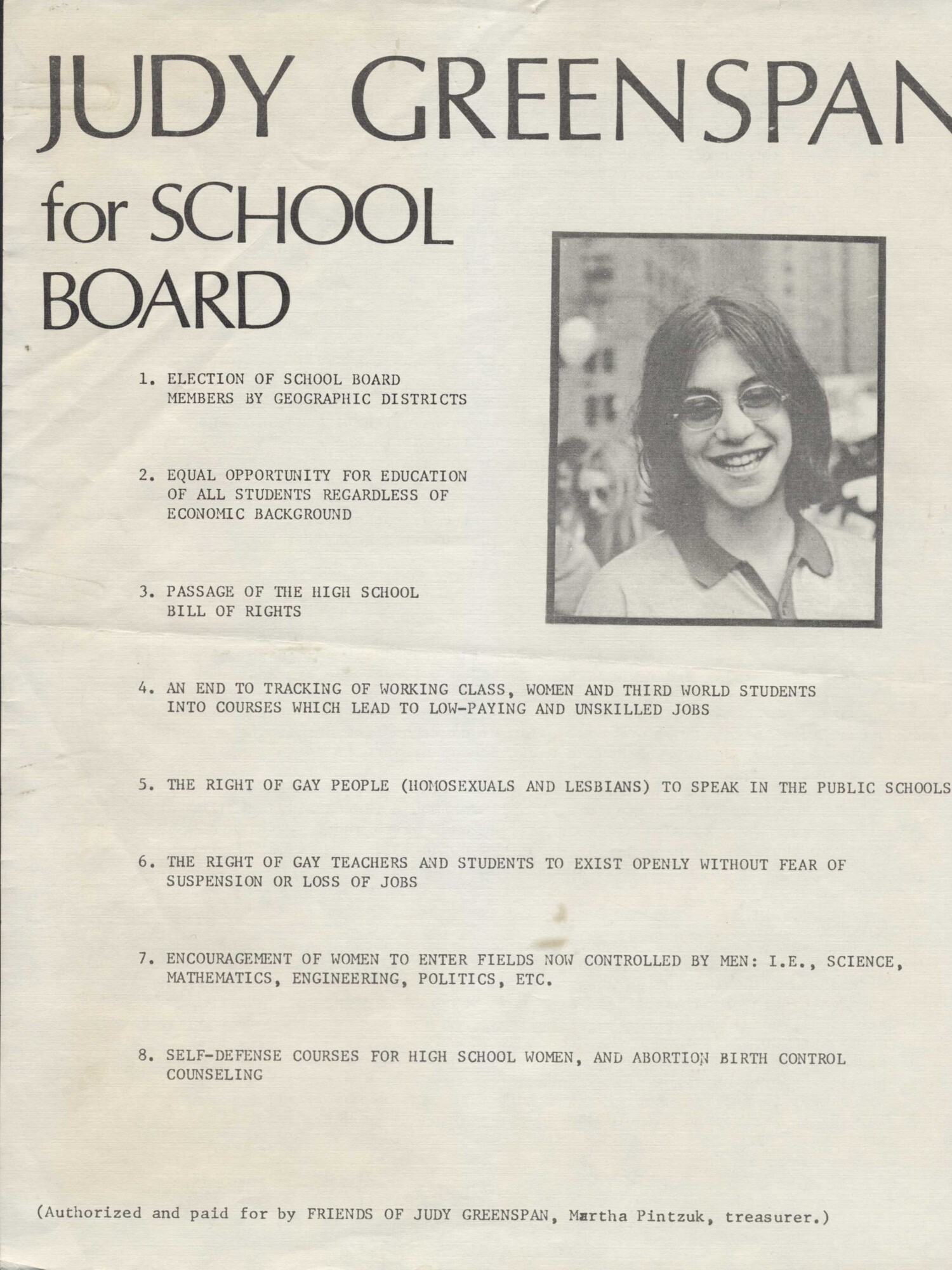

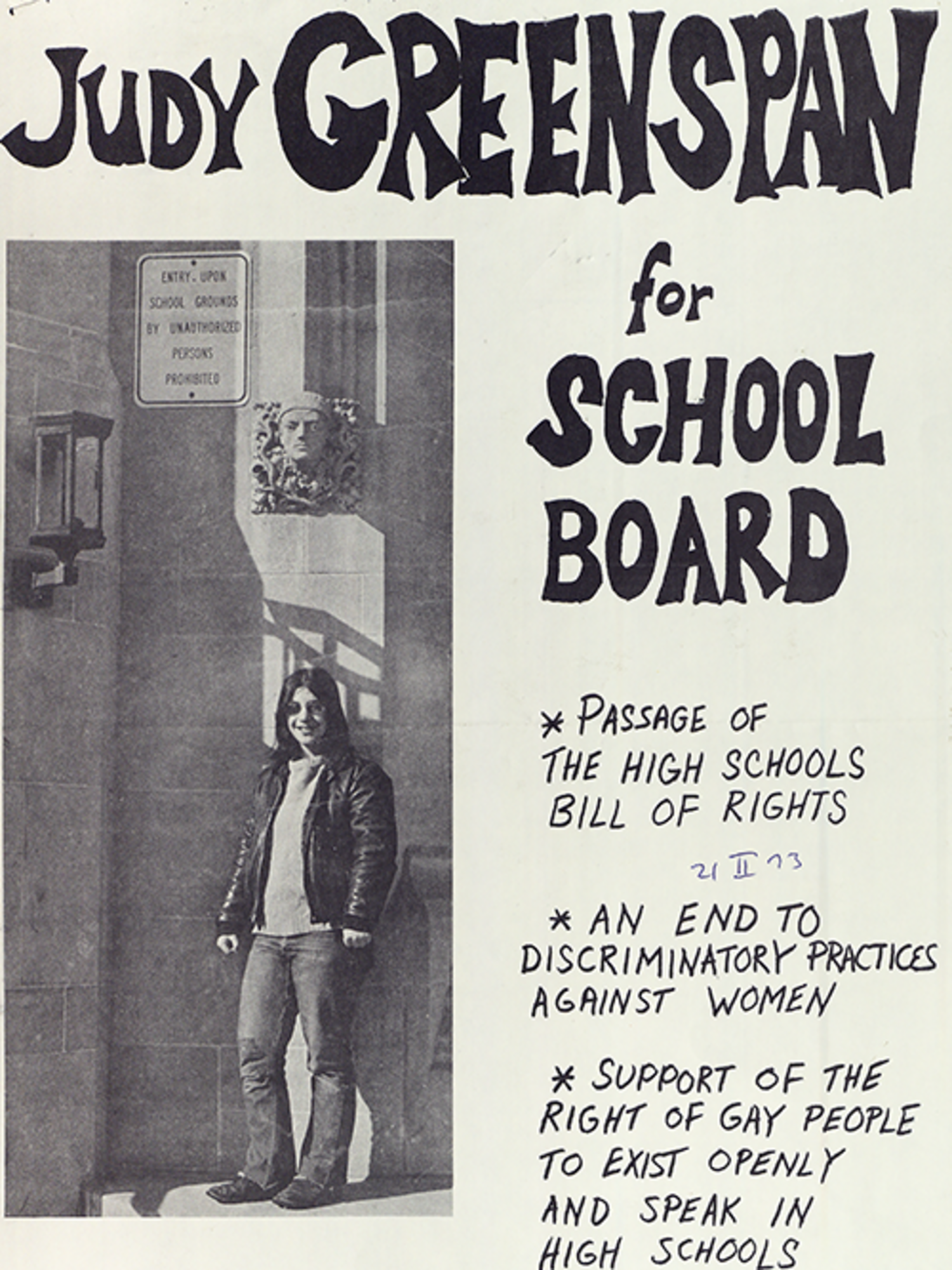

Judy Greenspan made history during their run for the Madison Metropolitan School Board in the early 70s at age 20. She was the first openly lesbian candidate to run for a publicly elected office in Wisconsin, and likely in the nation.

But Judy’s activist roots go back earlier than their days in the Capitol City.

While activists were fighting against the US involvement in the Vietnam War and for equal rights, LGBTQ+ rights were not yet a cause supported by the mainstream.

“The political movement in Madison -- and really all over the country -- was still very homophobic. It had not embraced LGBTQ rights."

"It still had really reactionary philosophies about how ‘oh, you can't be queer and be a revolutionary -- because that will turn off the working class, because they're all straight, right?’” said Judy.

Despite the homophobia, Judy was not deterred and they started searching for LGBTQ+ community.

That brought them to a Gay Liberation Front meeting. In that meeting, there were about 45 gay men -- and only one bisexual woman.

“I said I don't wanna do this, this is not what I need to find lesbians. They may not wanna come into a room full of 45 gay men,” said Judy.

But Judy says the final push out of the closet was their involvement in another group called the Bobby Seales Brigade, showing support for the Black Panther Party. The group was doing political studies on women’s liberation, reading the works of Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels and bringing in guest speakers among other activities.

One day, Judy went next door where one of the organizers of that group lived and suggested bringing in a lesbian speaker.

“And she looked at me, like well, this community is not very political. They are all into role-playing, none of them are radical…and so we don't want to invite them,” recalled Judy.

“So I knew I was a lesbian. I was like, yeah, you want to bet that they're not political? So that's what pushed me to come out…I said to hell with this shit!”

When Judy came out, their access to social movements changed. They said with homophobia prevalent in social justice movements, being an out lesbian effectively closed doors. But that didn’t stop them.

“I didn't feel comfortable trying to barge my way in. So I just sort of stepped back and said, OK, well, I'll just bring my political organizing to organizing in the lesbian movement."

"And there wasn't one, so I had my work cut out for me,” said Judy.

“We were small, very small when we first started. Together, we were able to light a fire, and I hope that that fire continues to burn."

Now out and wanting something different, Judy started the Madison Gay Sisters, which soon after was renamed the Madison Lesbians.

Part of what the group did was creating a phone line for women who thought they were gay. Using home phone numbers, people in the group would take turns staffing the line to talk with women who were going through struggles while coming out, like feeling suicidal or other issues.

“They were my community and some of them didn't like what I talked about and we just agreed to disagree,” said Judy.

While the group as a whole did not have a specific political line, many members would take part in protests as out lesbians.

“I think it was a May Day demonstration where we had a big banner which said ‘Lesbians Love Madame Bin’. Madame Bin was one of the military leaders of the National Liberation Front of Vietnam. So we carried that in the demonstration very proudly,” said Judy.

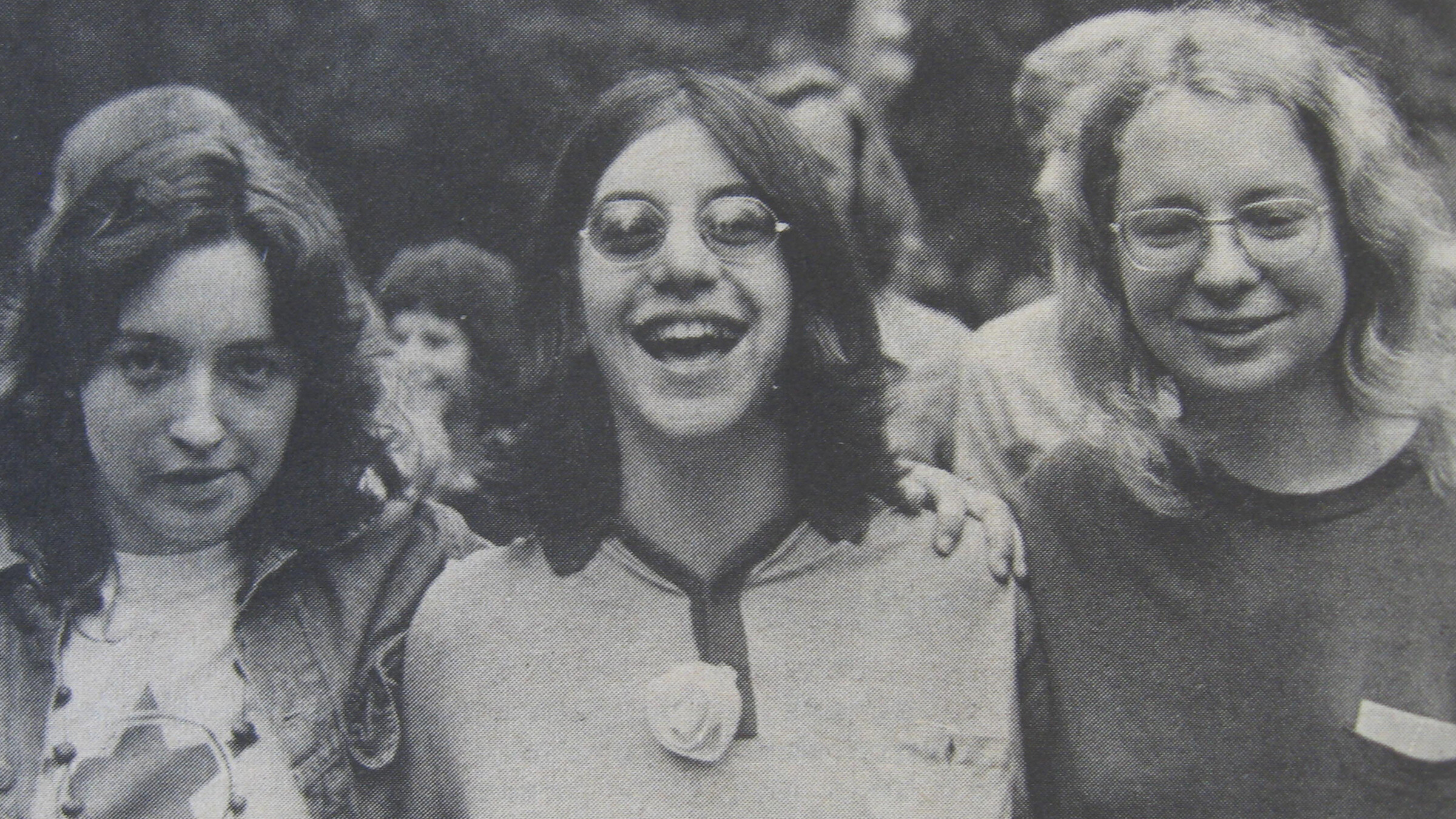

Judy and friends, 1972 (Credit: UW-Madison LGBTQ Archives)

Judy and friends, 1972 (Credit: UW-Madison LGBTQ Archives)

Judy says starting the Madison Lesbians was one of the proudest things they have ever done.

“To me, that was necessary, was needed. I think it opened the door for a lot of people to come out and get involved,” said Judy.

Another thing Judy did right away was join a softball team, though their time on the diamond didn’t last long.

“Of course, one of the first things I did was break my foot so I didn't like softball,” said Judy.

Time behind bars

In March of 1971, the same month Judy came out, protests took place over the use of non-union lettuce both on and off campus.

“We did a food riot and they didn't like that because scabs were working in the cafeteria, and so we went in, did a little guerrilla theory. Said ‘hey, there's scabs, that, you know, there's a strike going on, you shouldn't be in here eating.’ And we started to overturn tables and things like that,” said Judy.

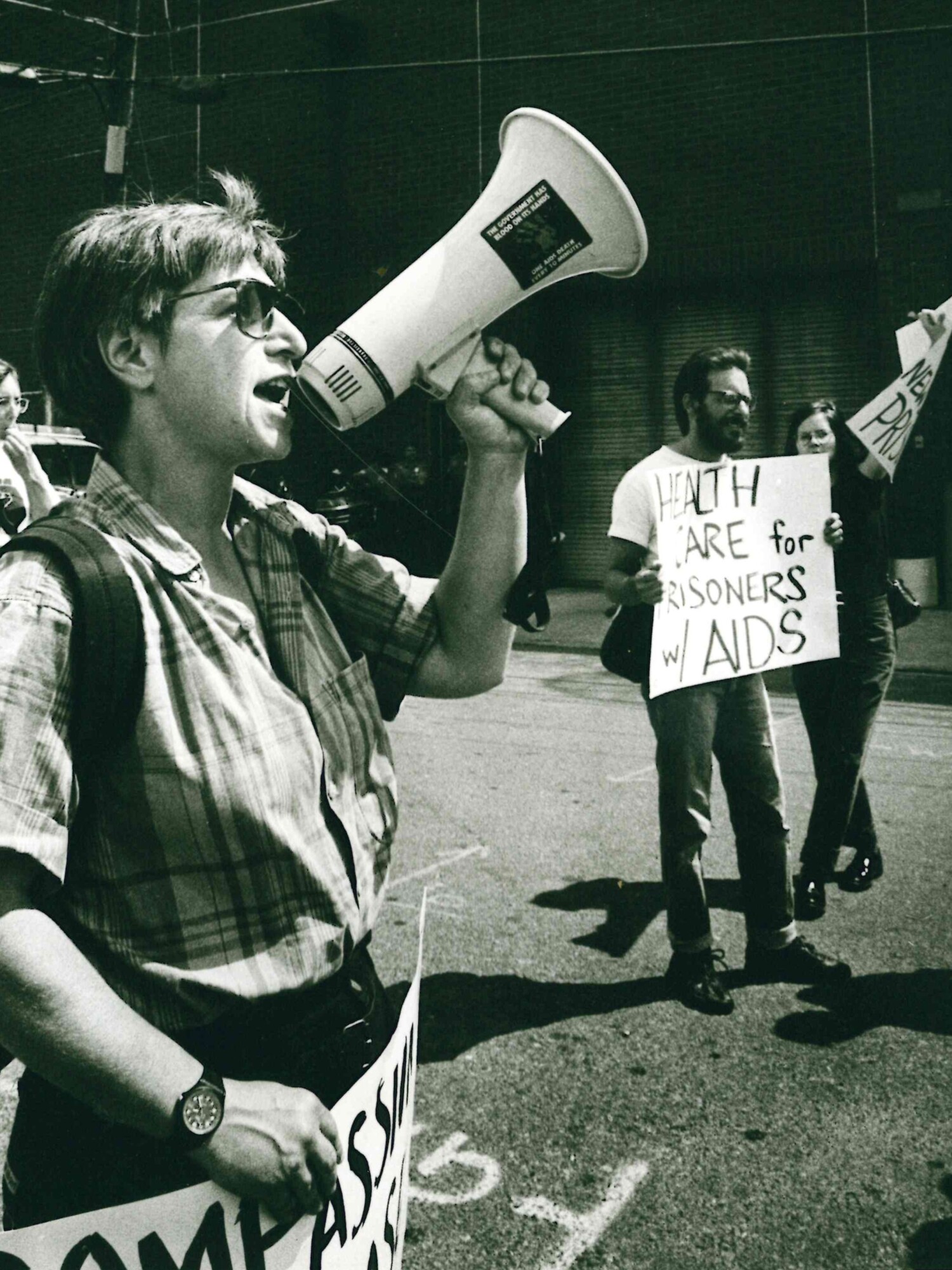

Judy leading an ACT UP Protest (Credit: UW-Madison LGBTQ Archive)

Judy leading an ACT UP Protest (Credit: UW-Madison LGBTQ Archive)

Judy today

Judy today

It was this demonstration that landed Judy and fellow students in the Dane County Jail for six weeks. Judy says in a time where it was almost unheard of for students to be jailed for demonstrations, two students were given six- to nine-month sentences, and Judy and another person were sentenced to two months.

“There's so many things that happened in Madison where people got, like, fines and, you know, more serious than us. He decided to throw the book at us. He just got tired of it,” said Judy.

Within those six weeks inside, more people were arrested while demonstrating. One night, a bunch of people were brought in after being tear gassed, and everyone yelled to get them help the whole night.

Judy says the women being held there for various offenses showed support to the people jailed during demonstrations.

“It's a different demographic between you and the rest of the prison population and the women that I met inside were so amazing, were so powerful,” said Judy. “We all tried to look out for each other and the women inside also did try to look out for all of us.”

Judy was part of the work release program, meaning they would often get visitors while working at McDonald’s. Soon though, they were fired because, “I couldn’t stand it and they couldn’t stand me,” and so, Judy spent the rest of their time in the program working for a different place.

Making Madison history

The Madison Lesbians would often collaborate with the Gay Liberation Front. Judy says they often spoke on panels for the GLF so that its speakers wouldn’t be only gay men.

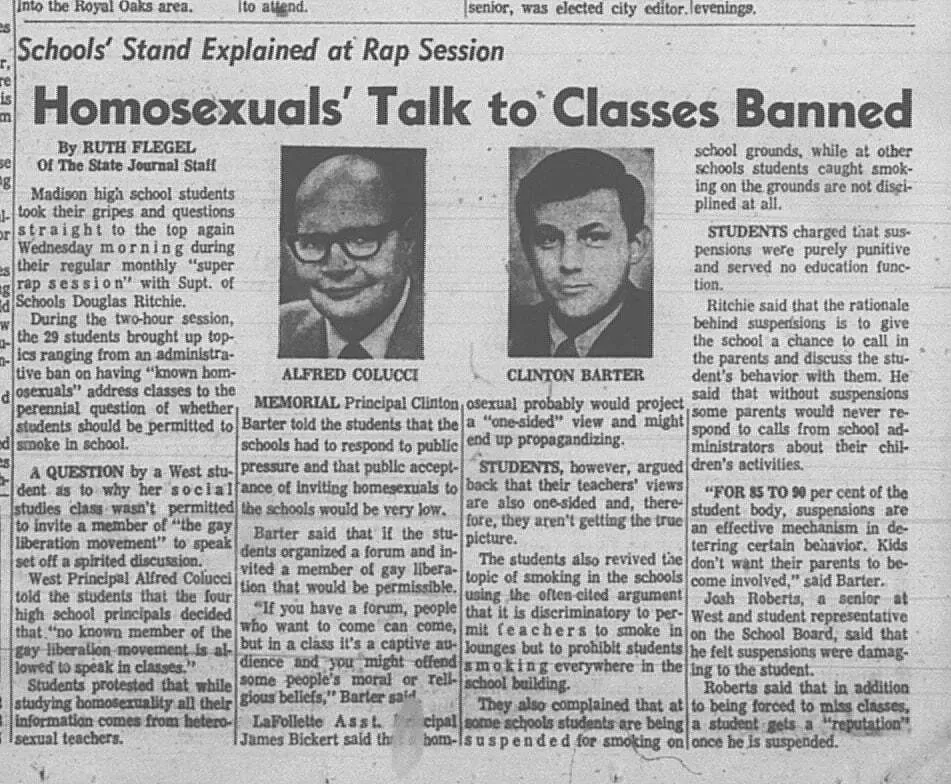

In 1972, a teacher at Madison East High School invited the GLF to speak to students about sexual orientation and gender identity. But when school leaders found out about this, administrators immediately cracked down, banning anyone in the LGBTQ+ community from going into schools to speak.

“The superintendent issued this edict that no homosexuals would be allowed to enter any of the public schools and speak, never mind the [LGBTQ+] students who go every day…and the thing that the Superintendent put out really sort of sent a chill,” said Judy.

The Madison Lesbians decided to push back on this by running a candidate for the Madison Metropolitan School District Board.

“I was the only foolish one who said, yeah, Ill run.”

The decision making a statement against the Madison Metropolitan School Board.

“As a candidate they couldn't stop me from going into the schools, I went into all the schools. They had already outlawed me and it was, this is like fuck you, superintendent,” said Judy.

The race was a contentious one, with a pool of nine candidates for two seats. Judy faced not only hostile crowds at times, but hostile competitors.

“There was an evangelical minister who was running for school board. Fortunately, they didn't win, but at every debate he would [biblically] condemn me,” said Judy.

Media coverage was not kind either. In an opinion piece posted in the Wisconsin State Journal, the writer called the school board cowardly for not outright banning “homosexual speakers”. The main angle people for the ban took was citing Wisconsin laws prohibiting gay people from having sex, as well as the law banning exposure of “harmful materials” to minors.

Ten years later, Wisconsin became the first state in the nation to put gay rights into law.

While the campaign had its struggles on the debate stage, it impacted Judy’s personal life as well. They were getting threatening phone calls. They were fired from both of their jobs after declaring candidacy: working as a bartender at a gay bar which is no longer in Madison, and as a custodian for a company downtown.

“I was bartending and the owner came in and said, ‘I see you're running for office…Cant have that type of thing here, we can't have that spotlight on us, so we have to fire you’,” recalled Judy.

“I just remember it was a tremendous amount of personal, emotional, and political energy.”

Organizing and running a campaign was all very new to the GLF and Madison Lesbians.

“We were trying to keep up with it all. We had just this little tiny, little machine of just a few people who were doing all the work,” said Judy.

At the same time, Toby Emmer was running for Dane County Sheriff. Emmer’s campaign was also a protest, and her group took Judy’s flyers and canvassed them both.

“Now today, if we saw that, a white woman with a rifle, we would go, ‘Oh my God,’ you know. But in those days, it was like a statement for here's a strong woman,” said Judy.

“Her group took my flyers with her flyers and put them out all over the place and helped it become sort of a real campaign in my mind.”

While it was a real campaign, Judy didn’t expect to win or even want to win. Their run was a political protest -- rather than a sincere attempt to make it onto the board.

"Known homosexuals" were banned from speaking in Madison schools in 1972.

"Known homosexuals" were banned from speaking in Madison schools in 1972.

“In any political struggle there, there are many tactics that you can use. And elections are actually a valid tactic, just as long as you maintain your integrity while you're doing it. You're not taking bribes, you're not going out to lunch with people who want to sway your opinion, or win your vote or anything like that,” said Judy.

“[I] did not want to be part of the system. Always, always wanting to tear down that system so I never wanted to bolster that.”

Judy says one particularly proud point of their campaign was an endorsement from the New Year’s Gang. Four men made up the group which is best known for the Sterling Hill Bombing in 1970, protesting UW Madison’s military connections during the Vietnam War. The Gang had called police to warn about the bombing, but it was not taken seriously; one person inside the building at the time of the bombing, 33-year-old postgraduate student Robert Fassnacht, was killed.

A key part of Judy’s campaign was supporting students and advocating for their rights.

In an interview with The Capitol Times, Judy said while much of the local media said Greenspan was running on a gay platform, they were running on a platform of equality.

“Somebody came out with a Students' Bill of Rights in the high school and we did a dramatic signing of it. Also we sponsored a self-defense workshop for high school students, women high school students during my campaign to sort of raise the idea that young women need to know self-defense so that theyre not preyed upon,” said Judy.

“We were just sort of in your face, like, with our middle finger up to the system the whole time.”

Judy lost the election, coming in fourth place with more than 6,000 votes, carrying the downtown wards. The Wisconsin Historical Society says their election helped foster greater acceptance in the Madison area, something Judy says is hard to measure.

“I feel like I was in a battle, so I don't know if I could look or think in retrospect. I don't think when I was in the midst of it that I felt like I was fostering anything. I mean, I was certainly making it impossible for them to ban us in the schools, or in the public institutions like they were trying to,” said Judy.

“But I don't know if I felt acceptance. I mean, it certainly brought out the people who supported us and that way they probably felt more empowered to come forward.”

No matter what their run did immediately, the campaign made history in Madison, and likely in the United States, as the first time an openly out person ran for public office.

“I don't know if that's true or not,” said Judy. “To me, its like, did I ever want this mantle? Not so sure. Id rather be the first queer person to lead a national demonstration or something.”

The end of their campaign meant an end of their time in Madison and as a Badger.

“I made a mess of my personal life during my campaign and I sort of got the heck out of Dodge. I just left that summer. I mean, I already quit school, but I think I was now officially quit,” said Judy. “I said no, there's many more important things happening than going to school, so I dropped out.”

From the Badger State to the Big Apple

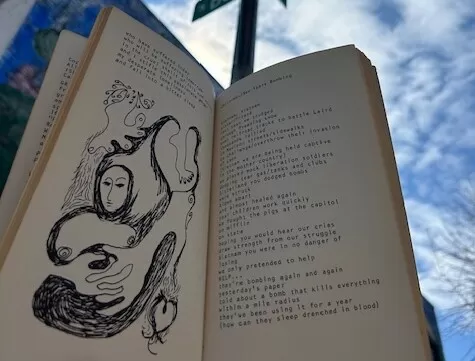

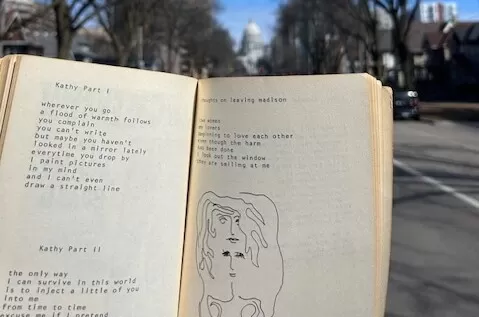

After leaving Madison, Judy moved back home to New Jersey for a couple of weeks before taking off to Brooklyn, New York with some friends. It was while there Judy became a published author with their works “To Lesbians Everywhere” and “We Are All Lesbians”.

“To Lesbians Everywhere” follows Judy’s life chronologically, many of it featuring their time in Madison. It came out in 1976, a time Judy says lots of lesbians were publishing poetry.

“There were a lot of people putting out poetry far better than mine,” laughed Judy. “I think all the poems are about Madison or about my experience in Madison. A portion about various lovers and also about political things, and also about when I was in jail. So I'm pretty sure it is some anger towards my high school history, high school journalism teacher, so definitely reflecting my youth.”

While Judy remembers the poems with fondness, some of the beliefs they held then are not what they still believe now.

“I look at that poetry book as a sort of in-your-face book. And you know, and I think that's what it was. I mean, did I believe that all women were lesbians at that time? I don't know. Do I believe it now? I don't, in fact. There are so many other labels now that people have put on themselves that I don't want to assume that anybody is a lesbian,” said Judy.

After a few years in Brooklyn, Judy moved to Milwaukee, deciding it was time to return to the Midwest.

Judy's poetry

Judy's poetry

Judy's poetry

Judy's poetry

Wisconsinite once again

Upon returning to Madison, Judy immediately got plugged into social justice movements again, including anti-war demonstrations, workers rights and LGBTQ+ rights.

One protest Judy remembers organizing was against the film “Cruising”. The 1979 film starring Al Pacino displayed stereotypes of gay men, often criticized as exploitative. Another film they protested was “Windows” which featured hateful stereotypes of lesbians.

Judy also became involved with the All People’s Congress, which was part of a national coalition. They also took part in protests against the “two hots and a cot” program where people would get two hot meals a day, work a “garbage” county job and have a cot to sleep in at night. Judy says they considered the program modern-day slavery and built a movement around that.

“I wasn't, like, super plugged into the LGBTQ community, although I went to the bars a lot,” laughed Judy.

Judy spent about ten years in Wisconsin before heading to Washington, D.C..

Amid widespread gentrification in D.C., Judy says while they often felt like a settler in a Black city, they did their best to avoid taking part in it.

Staying active and protesting stayed an important part of Judy’s life. In May of 1990, a rookie police officer shot and killed a Salvadoran man after Cinco De Mayo celebrations in the city. Daniel Enrique Gómez. The riots that followed became known as Los Disturbios de Mount Pleasant.

“I just remember running in the streets with a lot of young people. And I was like, I think I was like 35/36 years old, but I always had gray hair and this young, young, young Black child was running next to me and he said, ‘hey, grandma, you OK? Keep it up’,” recalled Judy. “I wasnt even that old! I said, ‘Im keeping up.’”

They also served as the National Logistics Coordinator for the 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

Advocating for incarcerated people is important to Judy, spending more than 20 years as a prison advocate. Much of their work was focused on people with HIV/AIDS held in prisons. They said this work was some of the most intense they have ever done.

“I saw so many people die that I had been trying to get out. I tried to get people out on compassionate release and was only very minimally successful,” said Judy.

Judy was part of San Francisco ACT UP, and founded HIV/AID in Prison Project of Catholic Charities of East Bay which worked with women with HIV and AIDS with a focus on compassionate release of those dying of HIV/AIDS.

“I worked as an advocate for people inside living with HIV at a time, when the very beginning of the epidemic, when there were no meds and all there was segregation and discrimination and lack of confidentiality. And there still is all that too, but Id like to think that maybe I made a little bit of a difference,” said Judy.

When their project ended due to a lack of funding, Judy started again with a new program, the HIV/Hepatitis C in Prison (HIP) Committee within California Prison Focus.

Once there was no funding for more advocacy work, Judy went back to the classroom. They went to the New School of California, which closed shortly after their graduation. Through intense writing assignments, long papers and taking tests, Judy was able to make up the credits they needed in about a year. Of course, their time in school meant more protests.

“The teaching profession is such a racist, such an exclusionary profession in the U.S. And when I was in it, you know, we had like 40 people in the cohort and there was one Black woman, and you know, and I think one Latina and that was it. There were, you know, white, mostly white and some Asian. And then the teacher teaching multicultural issues was this white woman from Minnesota."

"I felt like, what? What, who? Why are you doing this? So we walked.”

Judy and sister Mindy

Judy and sister Mindy

Judy and a friend in Mexico

Judy and a friend in Mexico

Back in the classroom

After graduating, Judy got into the classroom once again, this time as a teacher. Judy retired from teaching in 2019. But they soon got back into the classroom as a substitute once COVID-19 hit, decimating the teaching industry.

“I mean, already the teaching profession had been ripped apart,” said Judy. “So many vacancies.”

Now, they are in schools three to five days a week as a substitute teacher, often for middle school classrooms.

Judy used to lead the school’s GSA QSA, Gay Straight Alliance, Queer Straight Alliance.

“Getting to know them and realizing that the labels they put on themselves are very different like, like, pansexual, like, you know, some of the some of the others that they had to explain them to me I didn't understand,” said Judy. “But anyway, people don't use the same language, not just gay, straight... There's so many other expressive labels and some people don't want to label themselves at all.”

But since Judy is no longer an active teacher, and the other teacher who had taken over is no longer available, the students at the school are without a space to meet and talk about the current attacks on LGBTQ+ students from the Trump administration.

“I feel badly. I don't feel like there's a place for people, for young people to even discuss their concerns about this,” said Judy.

Judy is also part of multiple union committees and is at meetings for those almost every night. Judy says they see how Donald Trump’s re-election is on the minds of students.

Another major concern for students and staff is ICE raids, as the Trump Administration is allowing agents into previously protected spaces, like schools and churches. Judy says the kids are terrified, and teachers are prepared to physically block agents from coming inside, if that’s what it takes to protect children.

With the Trump administration's threats to cut federal funding for schools that teach about the history of racism in the United States and other threats, Judy says teachers will need to stay committed to teaching students.

“People are gonna have to teach outside of the book, which is what teachers have been doing for years anyway. You dont use the book, you make your own materials or you use Rethinking Schools,” said Judy.

Rethinking Schools is an education non-profit that creates material that promotes diversity and equity. The program started in Milwaukee in 1986.

Judy’s time in Madison continues -- and their reputation still follows them to this day.

“My students are all Googling me, because its all on the Internet, right?" laughed Judy. “They find my school board [picture,] and then they find my campaign photo, which they just don't get at all."

During Judy’s time teaching is when they came out as non-binary.

“Never felt like a she/her, hated the word ladies. But I didn't know what else there was to do other than, you know, other than to transition physically. For some of us old timers, she and he were the only two pronouns,” said Judy.

“Being involved in, in the progressive movement here, I've met many gender non-binary people, read about non-binary identity, and said, wow, this is me, this has always been me.”

They say students are always supportive, even if students get it wrong sometimes.

“Kids are really good at it, but I'm always correcting people. I'm trying to be known as 'just Judy' in the school setting, where its always Miss, Mrs. or Mr. So, I say, look, if you really need to put this little honorific, you can call me Mx."

"But I hate Mx. I just prefer Judy."

“The PE teacher, he just calls me Coach, Coach Judy or Coach Greenspan or something because he cant wrap his head around they/them, but he just says, ‘OK, let's put coach there’.”

Judy and daughter Johanna

Judy and daughter Johanna

Judy and granddaughter Jaya

Judy and granddaughter Jaya

“A lot of the young activists came up to me and thanked me. You know, they said you're the first old person that uses these [pronouns]. I said well, thank you, I guess. Thank you, I don't know,” Judy laughed.

Judy says the political state of the U.S. now is something they’ve seen before, and they’re witnessing more people come into their social consciousness.

“All of the sudden people woke up... and the movement pushed people into the streets who had never been in the streets before,” said Judy. “Well, the same thing happened. I got to see that on a massive scale with Vietnam cause I spent most of my life or most of my youth arguing with people about the Vietnam War being probably one of the few families in Elizabeth, New Jersey who opposed the war, arguing with people at school. Then one day people woke up and consciousness caught up.”

Since Trump’s re-entrance into the White House, more protests have been seen in cities across the U.S. People are demonstrating outside of Republican lawmaker’s offices across Wisconsin and the country, as well as showing up to town hall meetings to voice concerns.

Judy says people need to come together to fight for what’s right, and the legislation will follow.

“Were on the precipice of losing all of these social gains, whether it be Medicaid, whether it be, you know, powdered milk for pregnant women who are on whether it be welfare, all these life or death issues that he thinks like ‘I can just sign a notice,'" said Judy.

“Well, we're gonna see. I hope the rebirth of a movement that this country hasn't seen since the 30s, maybe itll be larger than the 30s…It would sort of behoove all of us not to struggle in our little niches but to try to broaden our movement so that we have really a united front.”

Since Trump’s return to the White House, he’s already tried to roll back protections of LGBTQ+ people, protections of immigrants and people living in the United States without legal permission, and has attacked education. That’s alongside major slashes to federal programs and budgets.

“I just changed my drivers license and got an X. And now Trump has gotten rid of gender non-binary. We'll see what happens,I think. But my advice is get ready to be busy,” said Judy.

“The attack is on all of us. The ruling class is very united. They don't seem like they are, but they are really united.”

While it’s been over 50 years since Judy last lived in Wisconsin, there’s much they remember fondly.

“I know the winters, but I honestly do not miss them. I do miss Wisconsin. I love Wisconsin.”

Starting various movements in Madison something they especially remember fondly.

“It was the beginning of the movement. You can't expect it to be super. I mean, we didn't tear meters and throw them at the police or anything like that, or tear up the bricks on the sidewalk like they did during Stonewall. But it was pretty in-your-face radical. But you know, it was also like, you know, building institutions, like self-help institutions and things like that.”

The Midwest culture is something they miss too.

“I feel like I had an opportunity to get to know people better, because it was just a smaller community, a smaller movement. Out here in the West Coast, people are not as direct as they are in the Midwest. On the West Coast, its more like they smile at you and then stab you in the back when you turn around. That type of thing is a little passive-aggressive out here so I miss the directness,” said Judy.

“It seemed to me life was a little simpler. But it could have just been the times. You know, when you work politically in a city where there's a very large movement and very many, many different groups and everybody having all different opinions, its harder to figure out how to get involved. Its harder to, you know, to really get to know people and to build things.

"When I was in both Madison and Milwaukee, there was a smaller movement. It seemed that coalitions were easier to be made.”

It’s been a few years since Judy last visited Wisconsin. They were scheduled to speak at the annual meeting of the Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network of South Central Wisconsin in Madison on September 12, 2001. That meeting was canceled after 9/11.

Judy's next visit, in 2022, was a quick one, featuring a reception, a Wisconsin Pride interview with PBS Wisconsin, and a drag show.

“It was sort of memory lane-ish. I drove around, looked at all the houses that I lived in, and they all look so different now. I was like, did I really live there? Really?” said Judy.

Judy says moving forward in these times means coming together, and they’re not pessimistic about whatever comes next.

“I think my life has been framed by sort of a tremendous thirst for social justice, but also revolutionary optimism. And I do have optimism, no matter how bad things are. And its that type of resilience and that type of optimism, which I think is very important that we all have as we move forward,” said Judy, choking up.

“We have to build an alternative to the government, to the powers that be. We have to build something that's really gonna fight for all the people in the country who are coming under attack and the world, not just the country but the world.”

And they’re not going anywhere.

“I'm old already. I'm still in the city. I'm going to march as long as I can continue to walk -- and then I might have to get a scooter.”

Judy and friend Annie

Judy and friend Annie

Judy Greenspan at a rally for educators, May 2025

Judy Greenspan at a rally for educators, May 2025

recent blog posts

May 31, 2025 | Andy Hartman

May 27, 2025 | Andy Hartman

May 19, 2025 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.