Larry Patterson: living the fabulous life

Larry was born on October 18, 1960. He was the sixth of seven children born into his large, extended North Side family. He grew up surrounded by aunts, uncles, cousins, and neighbors, first living near 12th and Burleigh, and later 6th and Wright. His mother knew, from an early age, that Larry was going to be different from her other children.

“My mother breastfed all her children,” said Larry, “and as a newborn, I just wouldn’t attach. I kept turning my head away from her, so she gave up, and bottle fed me. She thought, huh. This one is going to be unique!”

Even when he was a toddler, Larry was considered “feminine” by his family. He didn’t know “gay” or “straight” – he was just being himself. His family knew he was gay before he was. This might have been a challenge in another family – after all, it was the 1960s, and the African American community traditionally had rigid gender expectations – but not in Larry’s family.

“I never had to come out, because it was just kind of always known who I was,” said Larry. “It might have been an adjustment for my parents, and my family, but they adjusted fast. Everyone was incredibly supportive of me growing up – my sisters, my cousins – and I always felt protected. I grew up just being me, not ‘gay,’ not ‘straight,’ just me. There was no drama about it.”

When Larry was a teenager, his parents divorced, and he made friends with two young men from the Lapham Park homes.

“He and his brother were gay, and they had a group of friends who lived in the complex,” said Larry. “So, I found myself part of this big gay teenage gang by the time I was 14 or 15. These guys knew how to fight well, so nobody ever bothered us. Can you imagine, this bunch of little Banjee queens running wild, like we owned the place?”

"The Factory was all-welcoming, they rarely carded or hassled anyone. That dancefloor was a true melting pot. You felt a togetherness there that lasted long after you went home. Other bars weren’t so kind. They made it clear we weren't wanted.”

Some of his other favorites included C’est La Vie, the Phoenix, and Circus. He remembers his Sunday night routine: going to Elsa’s every Sunday, followed by a night out at Park Avenue.

“It was just the most glamorous of all,” said Larry. “It was like our own Studio 54. The closest thing Milwaukee had. We would always be on the list, so we didn’t stand in line. We paraded ourselves in front of everyone outside, and then walked right in.”

“I also remember going to the Baron, but that was very segregated, and always getting in trouble for it. There was a lot of drama between the separate groups of black queens who went there, but the music was really, really good. That made it worth it.”

He remembers the ruling black divas of the era, including Tina Capri. “I was such a big fan of hers, because she could really break it down,” said Larry. “I always called her the drag queen James Brown. She was up there sweating, and working, and singing, and really giving it her all.”

“Racism really showed its face to me when La Cage opened,” said Larry. “To me, the bar was just so racist to black customers, but I think that’s the reason we all kept going there so much – to prove ourselves.”

Lessons learned and taught

Larry still remembers his first boyfriend, Calvin, who was a year older. It was 1975, and the dating world was very new to him. While attending Milwaukee Tech High School, he “dated” a few older men – including one with a connection to one of his teachers.

“So, of course I got ridiculed in school, but it was mostly this circle of teachers who were making fun of me,” said Larry. “These Black female teachers would say mean things about how I walked, like I had more shakes than McDonalds, and they’d tease me in front of other kids.”

“So, get this, one day this teacher’s husband came to school, and I got this funny feeling about him. He was on the down low. We were both in the bathroom, and we looked at each other, and it was obvious he was interested in me. I told him I was home alone that night, and he came over. Now remember, I was underage at this time. While we were fooling around, I got his watch off his wrist and hid it under my pillow.”

“The next day, I went straight to the Queen Bee teacher who made fun of me, and she said, ‘can I help you?’ and I said, ‘yes you can. Give this back to your husband. He left it at my house last night.’ Boom. But that’s not all: I went straight over to Big Brenda and gave her the tea. And Big Brenda was the kind of girl that, if you tell her something during homeroom, it would be all over the school by second period. So, of course, it went all over the school.”

“I never heard a peep out of that teacher again, and her husband never bothered me either. I never forget that story. I never forgot her face when I told her!”

After graduating in 1978, Larry attended UWM as a dance and theater major.

“When I completed my UWM application, I said I wanted to be a music major,” said Larry. “Without as much as an audition, I was put in the music department. But everyone was much more advanced than I was, which left me wondering why I was there. My music professor came and watched me dance – and decided I needed to be a dance major. ‘You’re a natural one,’ she said, ‘you just need to be trained.’ So, I became a dancer. I even worked with the Ko-Thi Dance Company.”

“Every summer for four years, I would go to New York to study,” said Larry. “I loved it. I went to Martha Graham’s dance studio. I went to Studio 54. I went to Paradise Garage. I went to Jackie 60. I went to Fire Island. I found all the trouble.”

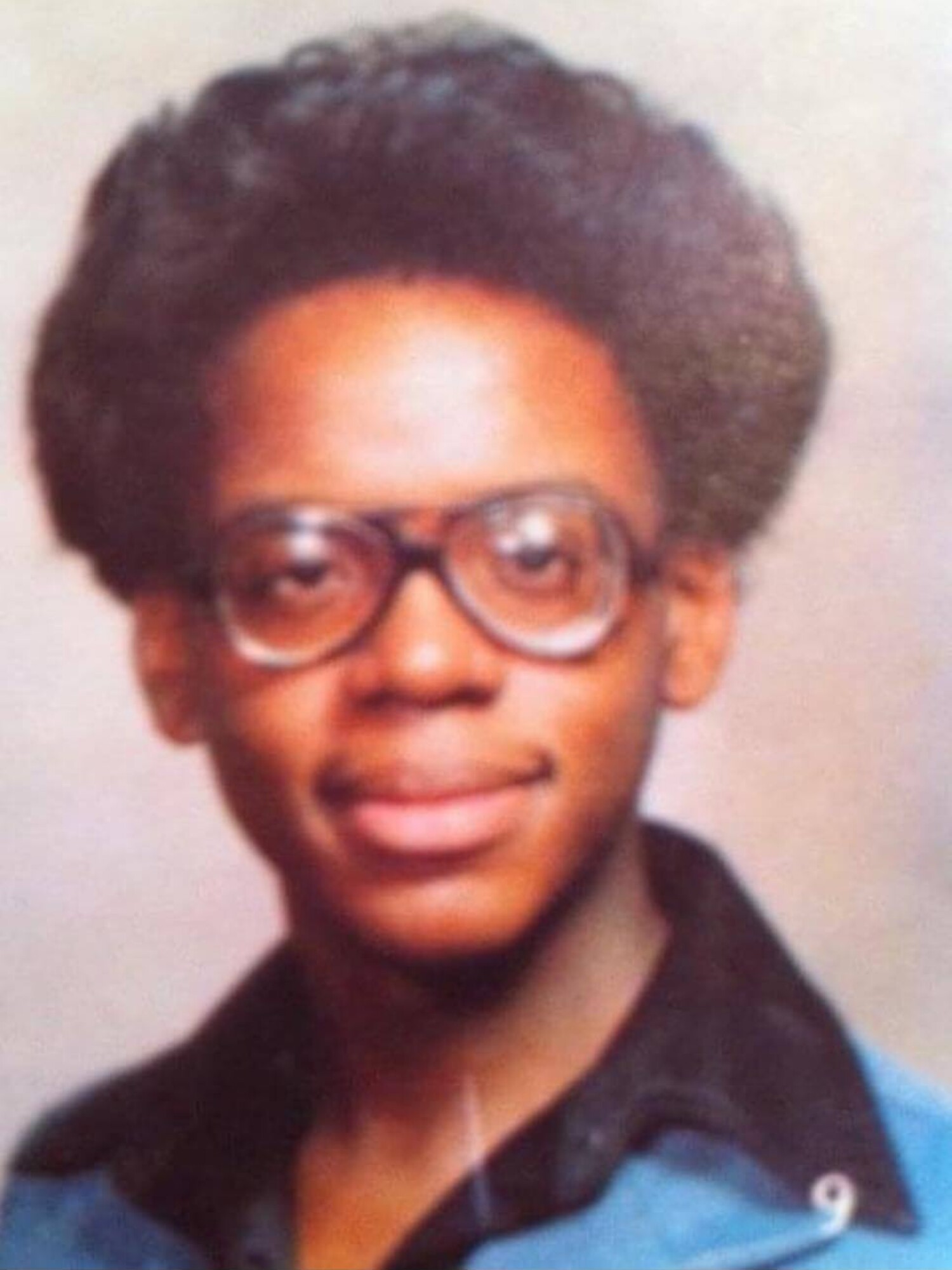

Larry Patterson

Larry Patterson

Career girl

He started his legendary run at Boston Store in October 1982. Although Boston Store ran for 121 years before closing in summer 2018, Larry remains – to this day – the most memorable and recognizable face of the brand.

“Boston Store was the best store in Wisconsin back then,” said Larry. “The store was really, glamorous back then, and it felt so much more sophisticated than Gimbels and more expensive than Marshall Field’s. I couldn’t believe it when I got hired there.”

Larry went downtown on a Thursday afternoon and completed a paper application. By the time he got home, Boston Store had already called and requested a next-day interview. On Friday morning, he met with a hiring manager. “I have a funny feeling about you,” she said to Larry, “I think you can do well selling fragrances. You know a lot of fragrances.” (“And meanwhile, I’m like ‘no, not really, but keep talking,’” said Larry.)

He applied Thursday, was hired on Friday, and started his training class Saturday morning. Little did he know this was just the beginning of a 35-year career.

“I had such a passion for what I was doing,” said Larry, “I learned so much at the fragrance counter. You receive so much training. You’re constantly learning. And you’re constantly meeting people. I don’t know where all the years went, but I had fun at work, something not everyone can say.”

Larry met many national celebrities visiting downtown Milwaukee’s last department store. Anita Baker came into the store, and her back-up singer offered Larry two tickets to the show. When Dionne Warwick arrived to promote her new fragrance, employees were told not to go behind the counter with her… so naturally, Larry went right behind the counter and befriended the singer. One day, a woman asked him for directions, and he asked, ‘has anyone ever told you looked like Natalie Cole?’ As it turned out, it was Natalie Cole. He met Linda Dano, Marie Osmond, Willem Dafoe, Chaka Khan, Bobby Brown, and many others over the years.

“The store was just thriving back then,” said Larry. “We’d have Capacity Days every fall, and it was our biggest sale of the year. It was so busy that people had to stand in line just to get into the store. And Federated took such loving care of their people. All you had to do was show up well-dressed and manage your area, because you’d do nothing more than ring people up for hours and hours. People were just everywhere in the store, just everywhere.”

"Little by little, the people just stopped coming downtown,” said Larry, “and corporate didn’t know how to manage that. So, they started shrinking the store more and more, and just kept on shrinking, and somehow that was supposed to bring business back. But they forgot that people liked Boston Store because it was a department store, not just a clothing or cosmetics store. They wanted housewares, toys, gifts. We didn’t even sell clocks anymore. We lost all the luxury brands and started selling only the low-cost lines. It became all about the coupons, not the quality. And meanwhile, the specialty stores had higher-end clothing and cosmetics, so why come to Boston Store?”

After being purchased by The Bon Ton, Boston Store began a long, painful collapse and closed in 2018. By that time, Larry had continued his fragrance career elsewhere, before joining the store opening team at Nordstrom Mayfair.

“As soon as I applied, the store manager told me ‘We’ve heard so much about you,’ and they just scooped me up,” said Larry. “Nordstrom treats their employees so well, just so well.”

Missing persons

In the mid-to-late 1980s, young men of color were disappearing in Milwaukee. Concerned friends and relatives reached out to police and media, only to be told nothing could be done. Gay men lived transient, secretive, anonymous lives, they said. They don’t want to be found, they said. At the same time, AIDS claimed more Wisconsin lives between 1986 and 1991 than any other years of the epidemic.

“When AIDS hit, nobody really knew what it was – even the people who got it,” said Larry. “The media told us it was a gay disease. God was punishing us. What I remember most is the medication. They put patients on a cocktail, and it really affected them in unusual ways, and everyone’s responses were different. I had a friend who would go berserk. Between the diagnosis and the treatment, AIDS really messed with people’s psyches. It was scary, just so scary.”

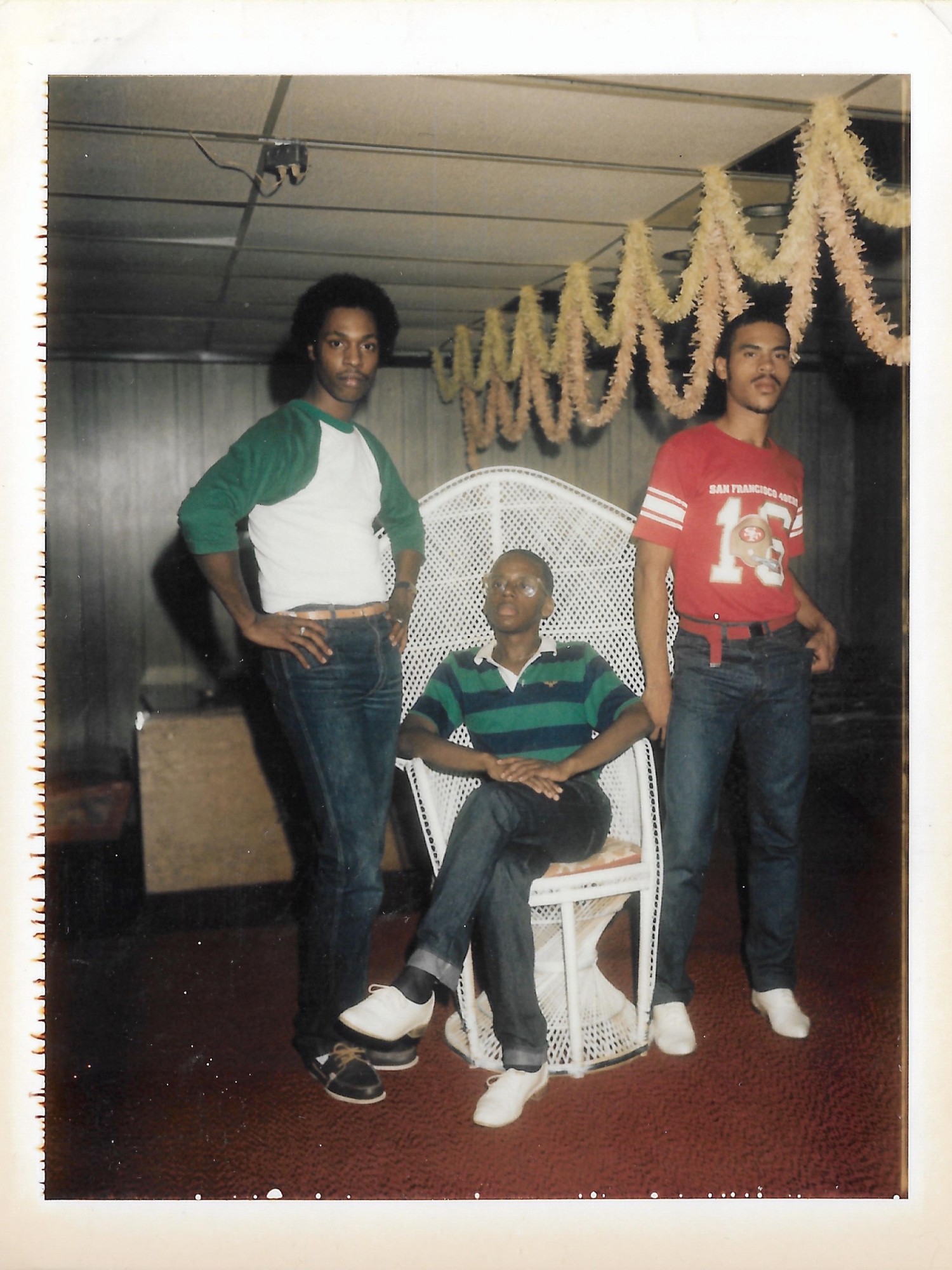

“I’ll be honest with you: when AIDS hit, I stopped having penetrative sex, even with condoms,” said Larry. “I was sexually active when I was young, but AIDS really redefined what sex meant. I cherish a photo of myself with two of my oldest friends, because we’re still here. Somehow, we’re still here, after losing so many friends. I’m still here and I’m incredibly grateful to still be here.”

“Today, people have access to Prep, which makes it so much easier to be debaucherous,” said Larry. “But it’s not 100% bullet-proof. Younger people don’t remember what we went through, they weren’t there to see people sick and dying in front of us. They don’t think the same way we do, after surviving a plague.”

But AIDS was not the only predator stalking young men of color. In June 1991, a random police encounter revealed that a serial killer had been hunting victims in downtown Milwaukee – a serial killer who had been a persistent and problematic customer at Larry’s fragrance counter. The Grand Avenue had become known as a regional cruising spot, and Dahmer found at least one of his victims, if not more, under its roof.

Outraged by police and media inactivity, Larry appeared on The Queer Program, a local cable access show, to demand justice for the victims.

“There was just so much misinformation,” said Larry, “about AIDS, about Dahmer, about everything. I had to say something. I had to call it out. It was the worst combination of homophobia and racism all at once. I’ve dealt with homophobia more from Black people than anyone, and I’ve dealt with racism more from gay people than anyone,” said Larry.

Closing thoughts

So, how did Larry become “fabulous” – earning the nickname that made him famous?

“Back when I was going to raves, we’d all be dancing, and I would just keep saying ‘fabulous’ all the time, and the name stuck. I used to go and kiss people and say, ‘oh, you look fabulous; oh darling, I’m fabulous.’ And suddenly people started calling me Fabulous Larry. It’s funny because more people know me as ‘Fabulous Larry’ than Larry Patterson.”

Now in his sixties, Larry is preparing for retirement. He plans to work a little, travel a lot, continue practicing self-care, and enjoy his life.

“I finally traveled outside the country a few years ago,” said Larry, “and now I’ve been to Mexico twice and Europe once. That was just so amazing. I have destinations to visit in Europe, Japan, and Hawaii. I just want to experience it all.”

He also plans to revisit the arts he studied in high school and college: music, dance, and band.

He prides himself on the lasting, meaningful relationships he’s built over the decades.

“Most people go through life with only 2 or 3 really good friends,” said Larry. “And I have so many because I’ve really connected with people. I’ve made a difference for people, and I try to encourage people to do what I do every morning. I get up, I open my curtains, and just give myself to the universe. I think once you give out positive energy, your will see positive energy return to you. I try to get my people to do that. Everyone’s family has drama. Everyone’s friends have drama. But at the end of the day, you all love each other. I have an amazing group of friends and coworkers. I was able to build a community of friends. And I think that’s the best feeling in life.”

“Technology has really changed our social lives,” said Larry, “and I don’t think people relate to each other like they used to. You go to a bar, looking for great conversation, and everyone is having conversations while also texting, swiping, emailing, scrolling, browsing… It’s interesting to watch people be in so many places at the same time. I have to wonder, are those connections lasting -- or fleeting?"

"In the old days, we’d go to a bar, meet someone, and take them home. Now, that’s happening in the cloud while everyone’s on their phones in public, and it almost doesn't feel real. There just seems to be a big disconnect where our connections used to happen.”

“In the end, I am really glad I never moved out of Milwaukee,” said Larry. “This has been my home. I’ve been able to make a name for myself here. I’ve gotten involved in things that matter. I’ve always thought about moving – San Francisco, New York – but I never actually moved."

"I’m like an old oak tree. I have deep roots in the city and I’m going to be here long after I’m gone.”

Larry Patterson

Larry Patterson

recent blog posts

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 10, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.