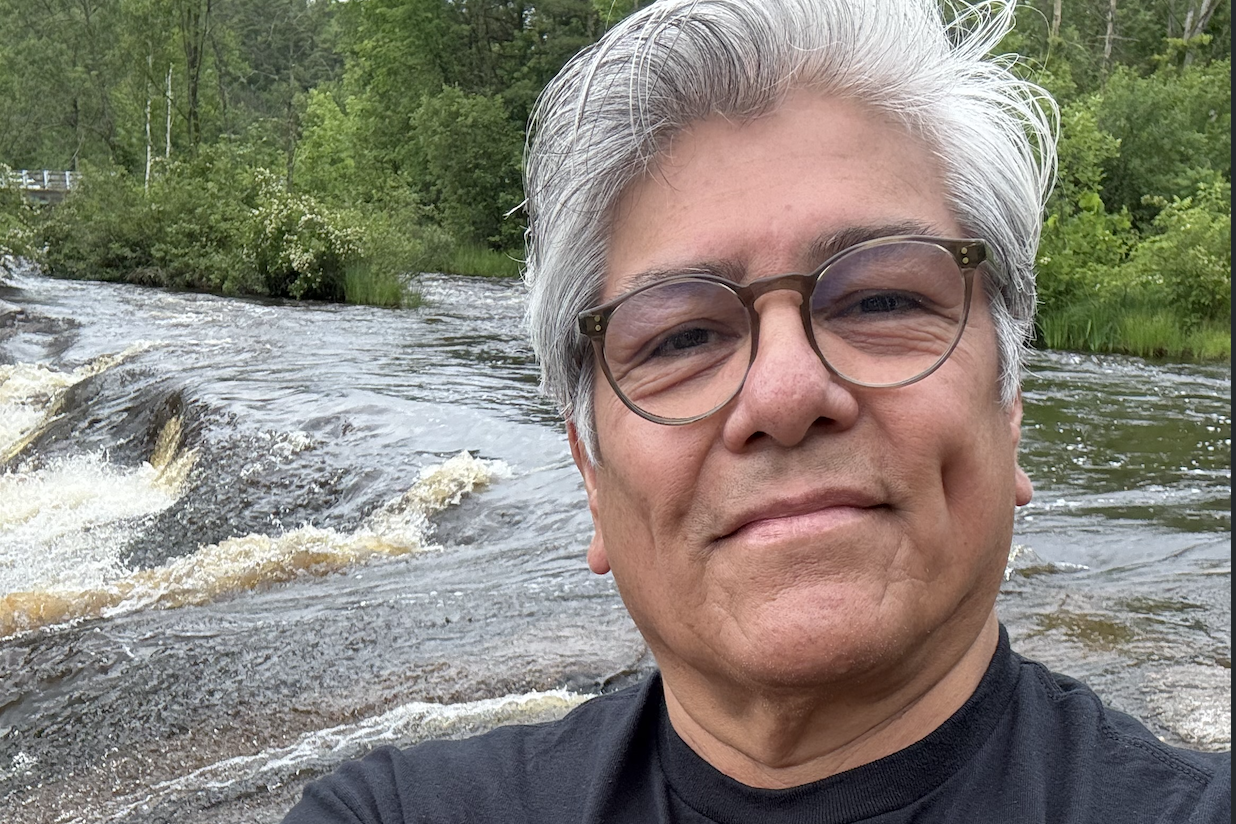

Michael Waupoose: accepting sacred responsibilities in a divided world

“Being Two Spirit means there is a responsibility to your family and community, to be a teacher, mentor, and elder."

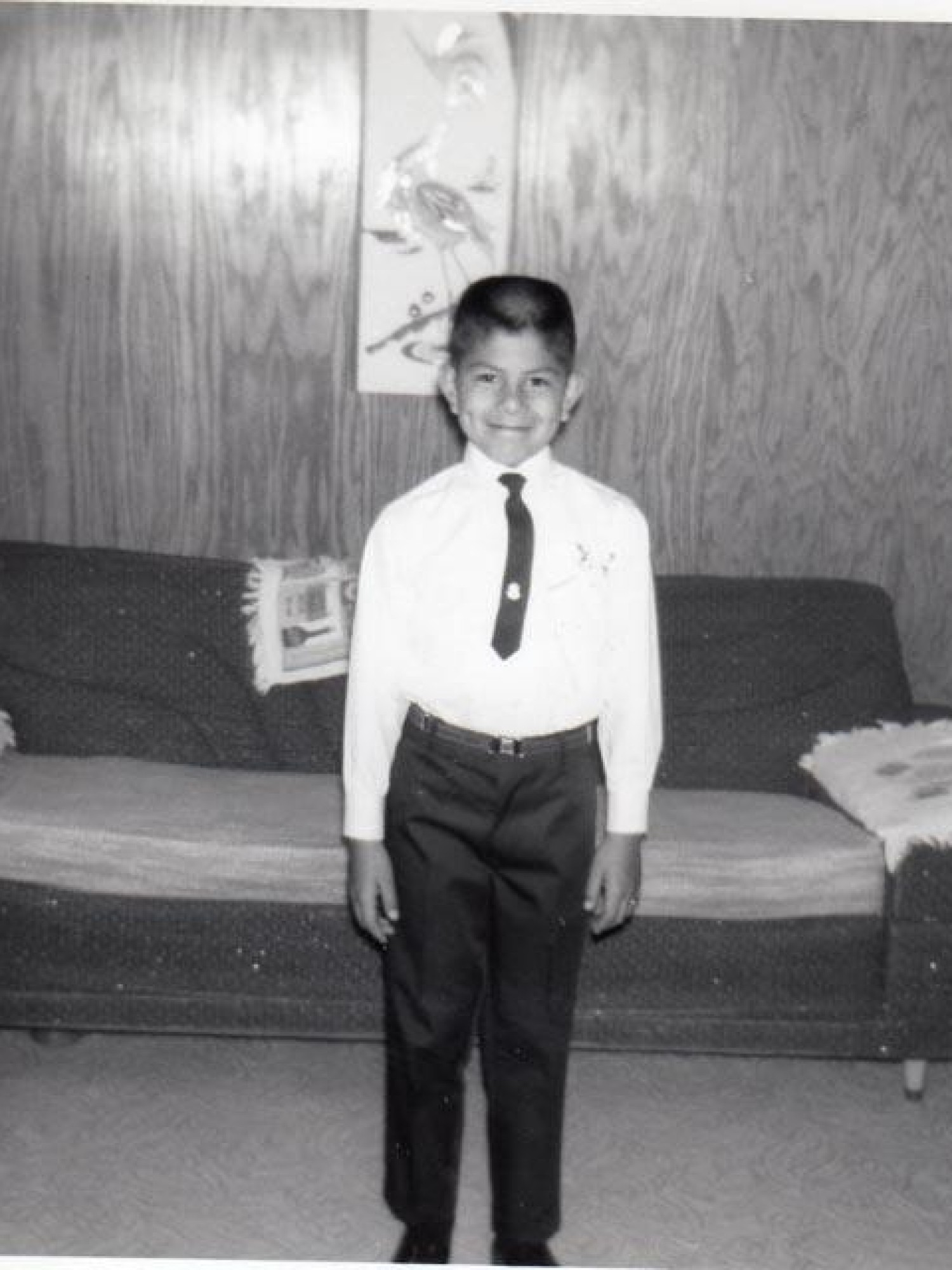

The second-grade classroom in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, was meant to be a place of learning, but for a young Michael Waupoose, it was often a stage for a cruel form of performance.

It was Thanksgiving season, and his teacher, in an attempt at cultural inclusion, had the other children craft paper "Indian headbands." Then, she would call on Michael, the only Native American child, to stand before the class and "do Indian dances."

“I don’t remember seeing a single person of color in my grade school, junior high, or first year of high school,” Michael recalls now, speaking from his life in Madison, where for the last 31 years he has built a life of sobriety, professional success, and profound self-discovery.

That moment in the second grade—a mix of forced performance, curiosity, and deep-seated othering—was a symbol of the tension that defined the early years of his life. It was a tension born of systemic oppression, discriminatory federal policies, a tension between being a proud Menominee while being encouraged to "blend in," and later, a tension between his identity as a gay man and the life he was forced to live.

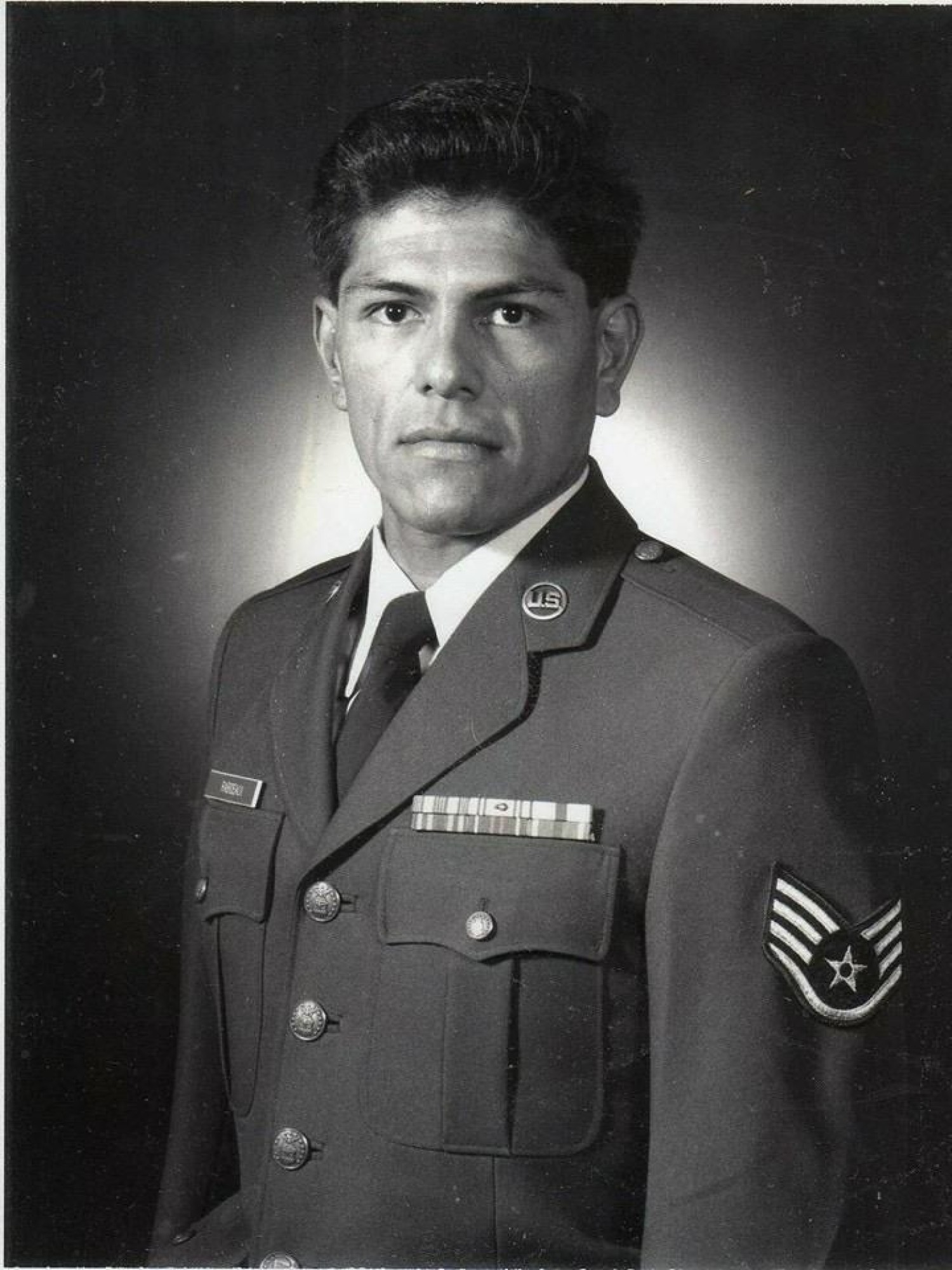

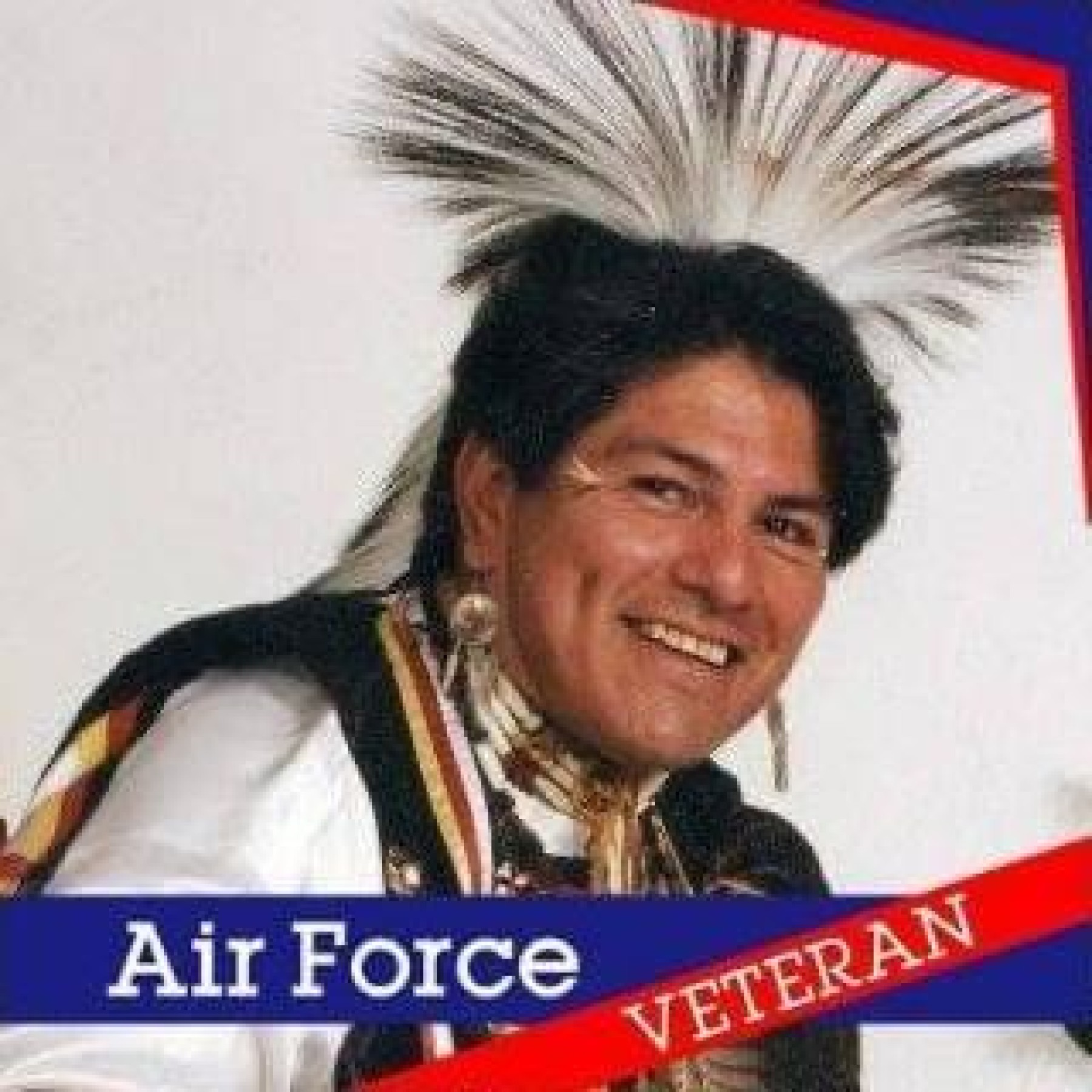

Michael excelled, earning numerous awards and recognition, reinforcing his hunch that queer people and People of Color in the military often over-performed. His success led to a recruitment attempt by the Air Force Office of Special Investigation. The job was intriguing, but the extensive background check it required —including interviews with people in Sheboygan and Oshkosh — was wrought with anxiety.

“I knew I would not pass. My identity would come out,” he explains. “The risk outweighed the possibility of joining. It was another one of those ‘I wanted to do this, but being outed as gay was too much of a risk moments, so I chose not to do that.”

The fear was corrosive. When he reached the point of deciding whether to re-enlist for a second term that would eventually lead to a decision to stay until retirement, he chose to leave. He was exhausted by the constant burden and had found his career as a substance abuse counselor rewarding and fulfilling.

“I didn’t want to live with that lingering fear always hanging over me,” he states.

In 1984, a drunk driving ticket had led him to treatment and, ultimately, sobriety. It was in that recovery setting that he began to acknowledge the direct, dualistic relationship between his oppressed identities—being Native in a white world, being gay in a straight world, and being sober —and the internal pressure he had been carrying. He had to keep these identities "hidden, unspoken."

Sobriety allowed him to begin the hard work of reconciliation.

He understands the monumental effort required. Tribal governments are already pulled in countless directions—language revitalization, treaty rights defense, fighting major corporations like Enbridge Oil Pipeline, and ongoing land rights disputes (such as the recent State Supreme Court case defending the Menominee right to place purchased land into trust). Yet, he believes the courage and wherewithal for this movement must come from within the 2S community and allies, with advice and encouragement from elders.

“What do we want to see for the seventh generation? What tribal values do we need to restore and reinforce?” asks Michael.

Michael also addresses the ongoing challenges of appropriation, which he has dealt with his entire life—from white people claiming Native heritage for financial or professional benefit to the colonial invention of blood quantum, which limits tribal enrollment and access to treaty resources.

The blood quantum requirement creates an ironic, cruel dynamic: children who are raised on the reservation, steeped in culture but slightly below the required blood percentage, are excluded, while others who are completely separated from the identity may claim descent based on a tiny fraction of blood. The rule is “really quite a disruptor,” reducing resources for Menominee families and blurring the true identity rooted in community and upbringing.

Hanging in there, after all these years

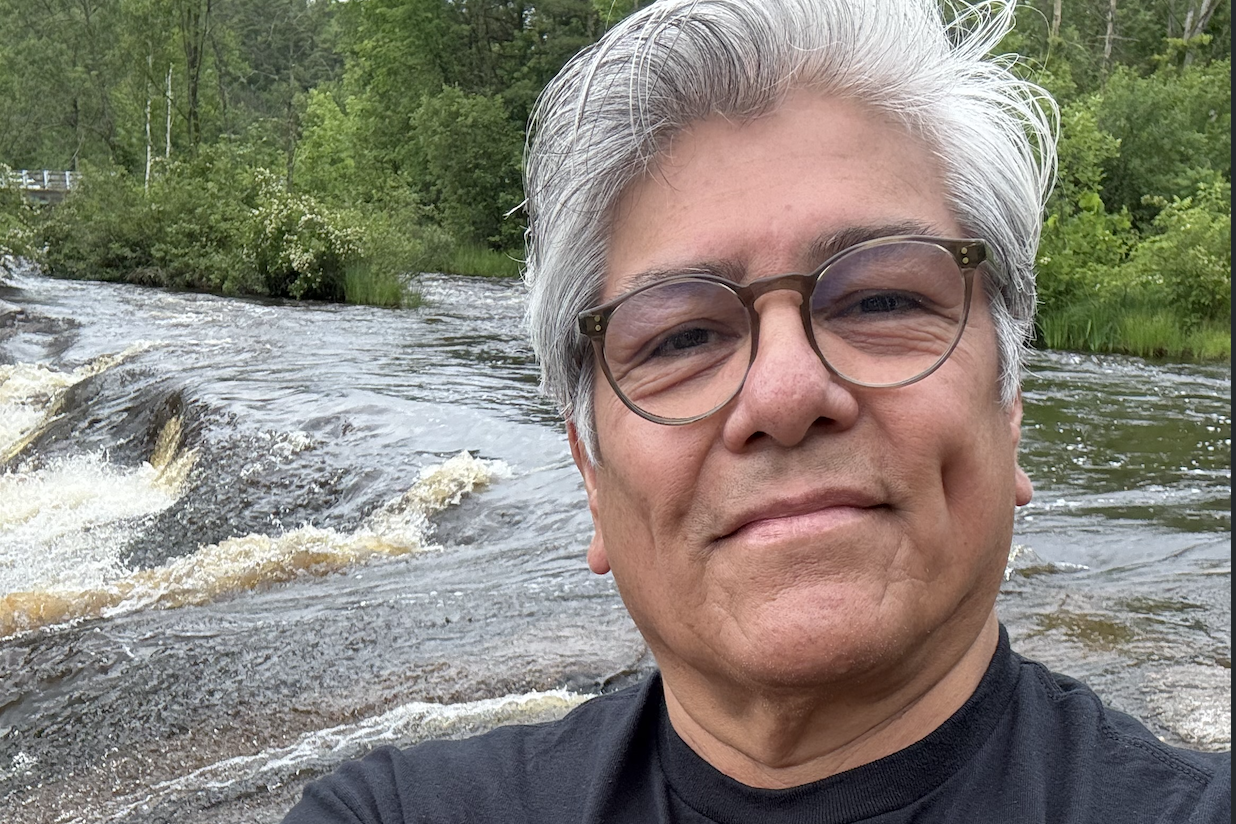

Michael Waupoose’s life has been a slow, powerful integration of all his separate, formerly contradictory identities: the behavioral health clinic director, the Menominee man, the sober addict, the husband, the elder, and the Two-Spirit person. None is stronger than the others; they are strongest together.

Reflecting on his hard-fought path, he offers advice to his younger self: “Hang in there.”

He credits his survival to the simple, profound truth he learned as a clinician.

“A kid needs at least one person in their life that unconditionally loves and supports them.”

For him, that person was his grandmother, whose quiet, non-verbal presence was everything. When a family member attempted to shame Michael for coming out, a beloved aunt told him: “nothing they said was true, because your grandparents loved you to the moon, no matter what.”

That unconditional love stuck with him. It is the lesson he now imparts to his nieces and nephews.

“My commitment to you is to be here when things are going well and not going well. Nothing will change the fact that I love you.”

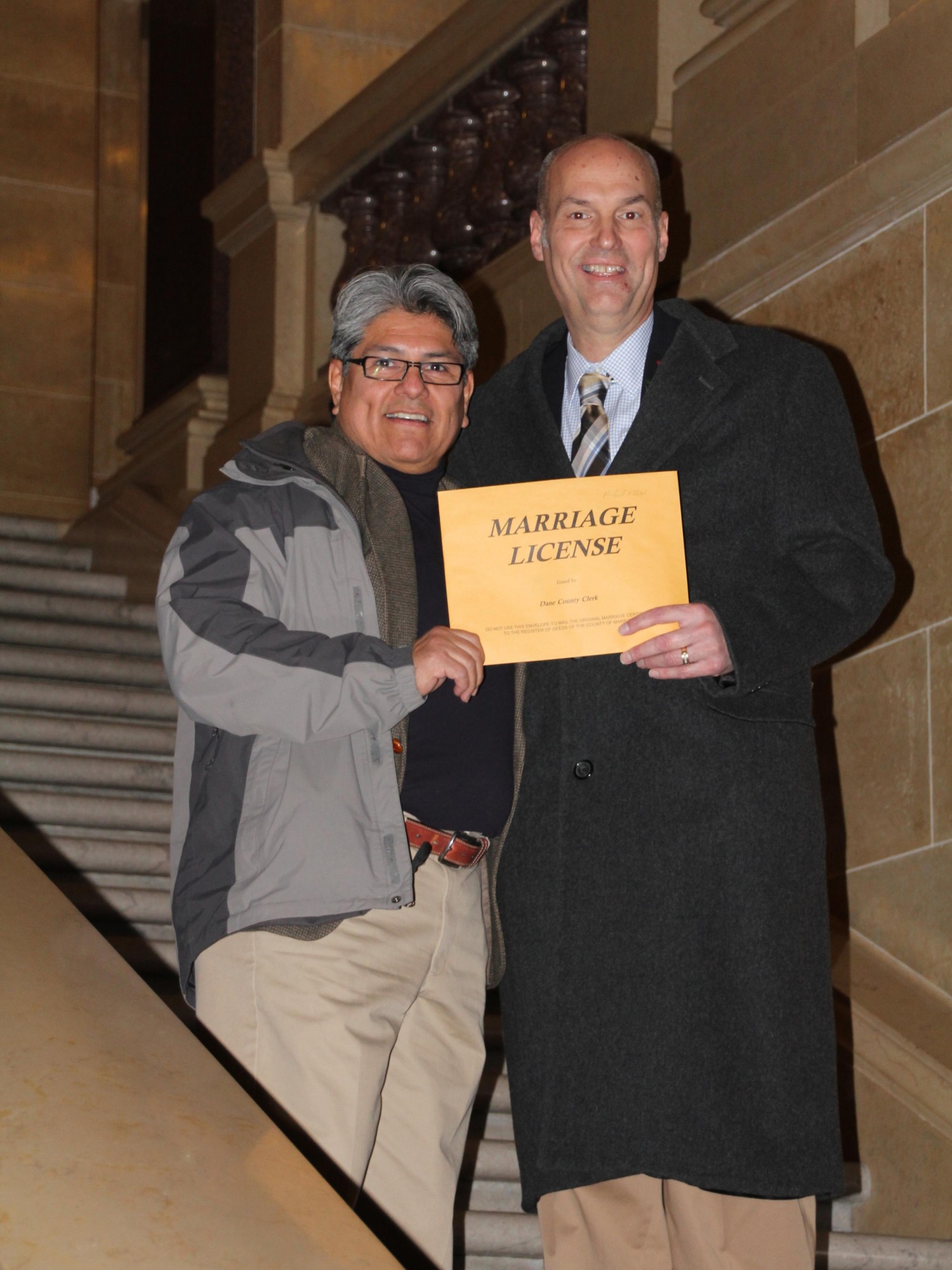

He never could have imagined his life today—the success, the stability, the 30-year relationship with his husband, the respect, and the ability to serve his community. As a final, powerful act of integration, Michael is now redoing his ceremonial regalia for the upcoming 2S Pow Wow in June, ensuring it will visibly reflect the fullness of his identity.

The forced separation is over. After a lifetime of being asked to blend in, to hide, and to perform, Michael Waupoose stands fully revealed, defined not by what he lacks, but what he offers, and by the sacred responsibilities he embraces.

“One day I will be an ancestor and I want my descendants to know that I used my voice so that they could have a future.” - Autumn Peltier.

recent blog posts

February 14, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.