Patrick Firgens: surviving and thriving in his ninth life

"Recognizing that I was Two Spirit was like a flag being raised in my soul."

The scent of burning sage is the first thing Patrick Firgens remembers. It is the smell of home, the Menominee Reservation in Wisconsin, a place he spent a lifetime fighting to leave, only to return and discover it was a place where he could truly thrive. Now, standing in a community center, circling a dozen faces—some Native, some non-Native, but all searching for peace—he lights the smudge, sends the smoke skyward, and begins the recovery talking circle.

“Survival is the name of the game,” he tells them, his voice carrying the firm, clear tone of someone who has stared down death more than once. “Survival is who I am. I am not a victim.”

Patrick is a man who speaks in lifetimes. By his own count, he’s lived eight already. The ninth, the one he is living now, is dedicated to healing, sobriety, and reclaiming his ancestral role as a Two Spirit. His journey is a dizzying kaleidoscope of trauma and triumph: a childhood marked by bullying, a spectacular career as a nationally celebrated celebrity hairdresser, a descent into drug addiction in the shadows of Milwaukee nightlife, and extraordinary battles against life-threatening medical issues.

“He knew I was gay, although I never told him, and he looked out for me. I can still hear the click click click of his cowboy boots on the high school hallways.”

Patrick took his destiny into his own hands and sent himself back to boarding school for 11th and 12th grades. There, he excelled, becoming student class president and finding a solid foundation of friends.

Upon graduating in 1991, Patrick made his second great escape. He recognized that he couldn’t be himself on the reservation, where gay men got beat up simply for being seen at the local bars.

“I fought my ass off to get off this reservation, and I told myself that I was never coming back here,” he told himself.

He went straight to beauty school in Green Bay, where he truly started to blossom.

Later, he tested positive for Hepatitis C, which is very dangerous for people with HIV. Patrick’s prognosis was not good, and he was again told that he had a low chance of survival. Once again, Patrick did not listen. He entered rehab, became clean and sober, and got tested again. The virus was gone. His body had fought it off and killed it.

“You are one in a million,” the doctors told him. “You are a true medical miracle.”

He’s overcome several drug overdoses, near-fatal car accidents, and even being chased through the Third Ward by a man with a knife.

“But I’m still here,” he said. "I wasn't kidding when I said, survival is the name of the game."

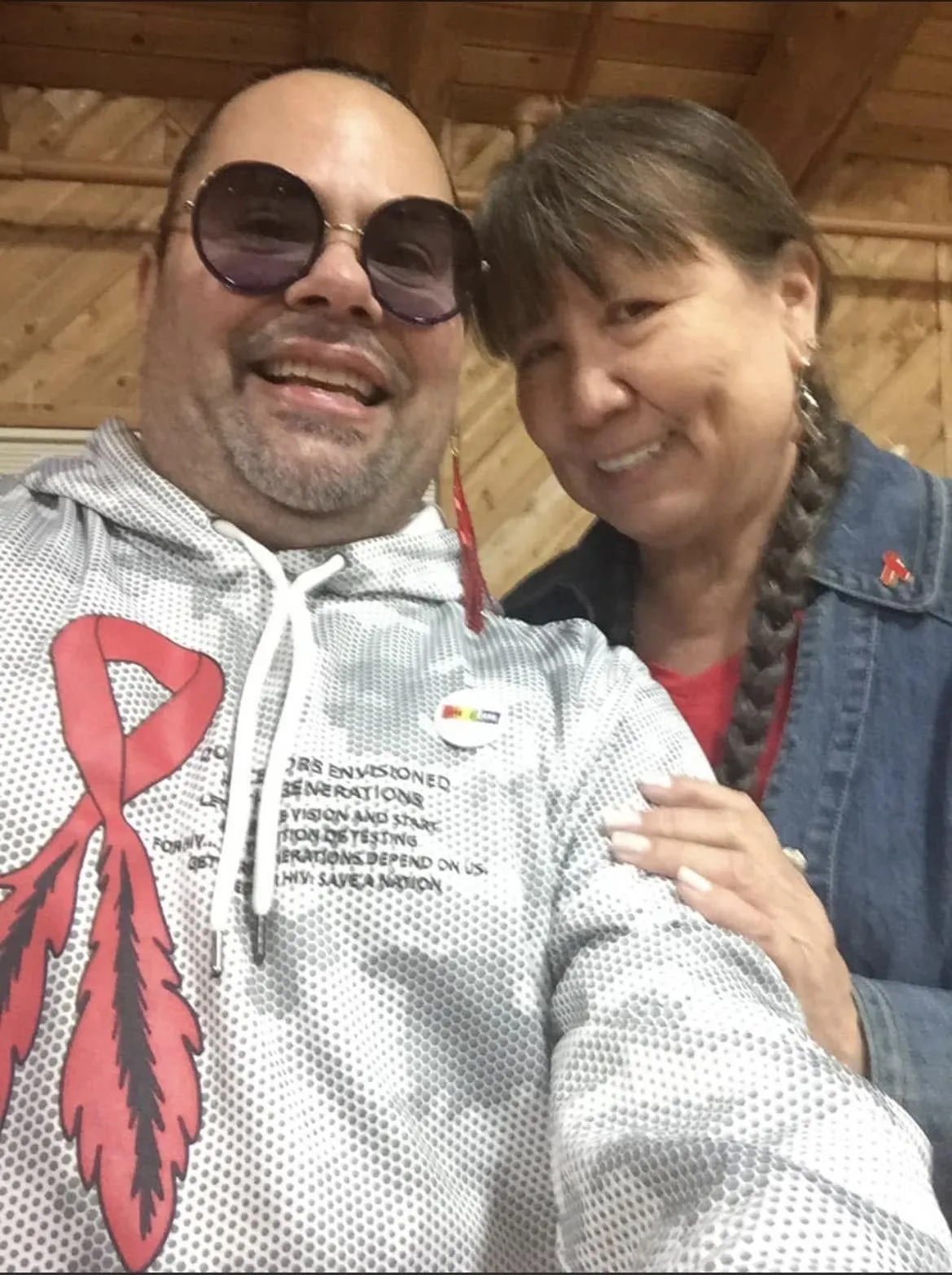

Now at home on the reservation, his family supports him 100% -- and holds him to a high standard of self-care. This healthy, loving, nourishing environment allows him to focus on healing himself and others.

“When I left here, I was dying to leave here, and now I see the reservation as a haven, a place where I can heal and learn and grow. This is a place where I can become who I was always meant to be. I can grow old here, and I can also grow wise here.”

Patrick knows that his ninth life is a life of purpose, and that his journey of the Two Spirit guide has only just begun. To anyone struggling against their own darkness, Patrick offers a simple, powerful message of hope:

“If you would have told me 40 years ago where I’d be today, I would never have believed you. I am lucky to be alive, and I am only alive because I kept fighting to live. When you fight the good fight, you’ll always win every battle – even if that battle is with yourself.”

recent blog posts

February 24, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 21, 2026 | Meghan Parsche

February 14, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.