Robert Lambert: an outrageous life of avant-garde activism

“We had access to everyone -- and we could do anything."

From a painful childhood in the Midwest to the epicenter of 1970s counterculture, and later-life international acclaim as a food artist, Robert "Bobby" Lambert has lived a life less ordinary.

As a founding member of the legendary art collective Les Petites Bon Bons, Lambert helped redefine the boundaries of art, gender, and social commentary, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape.

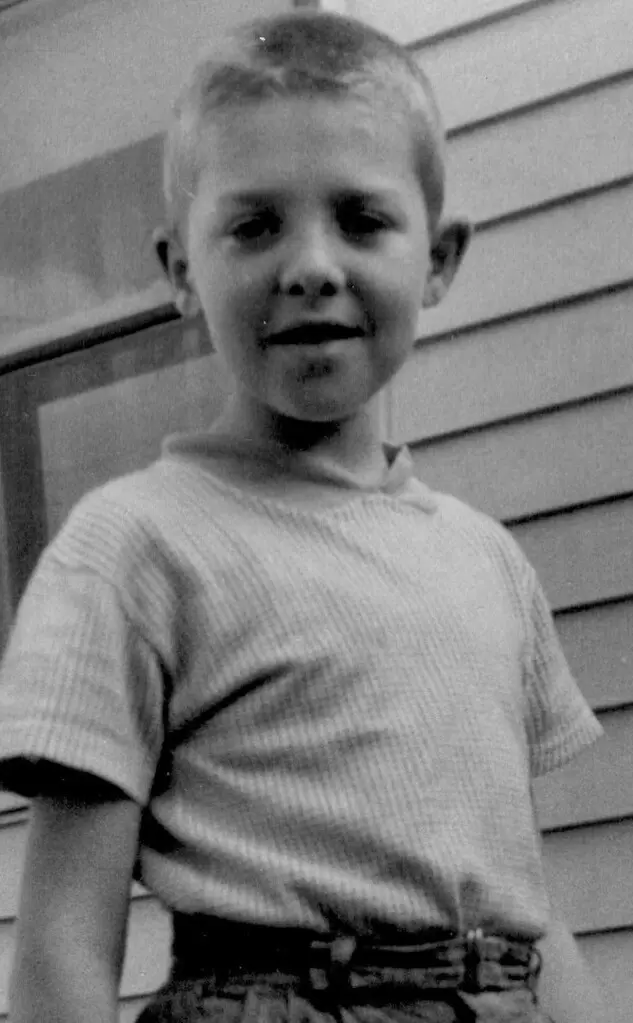

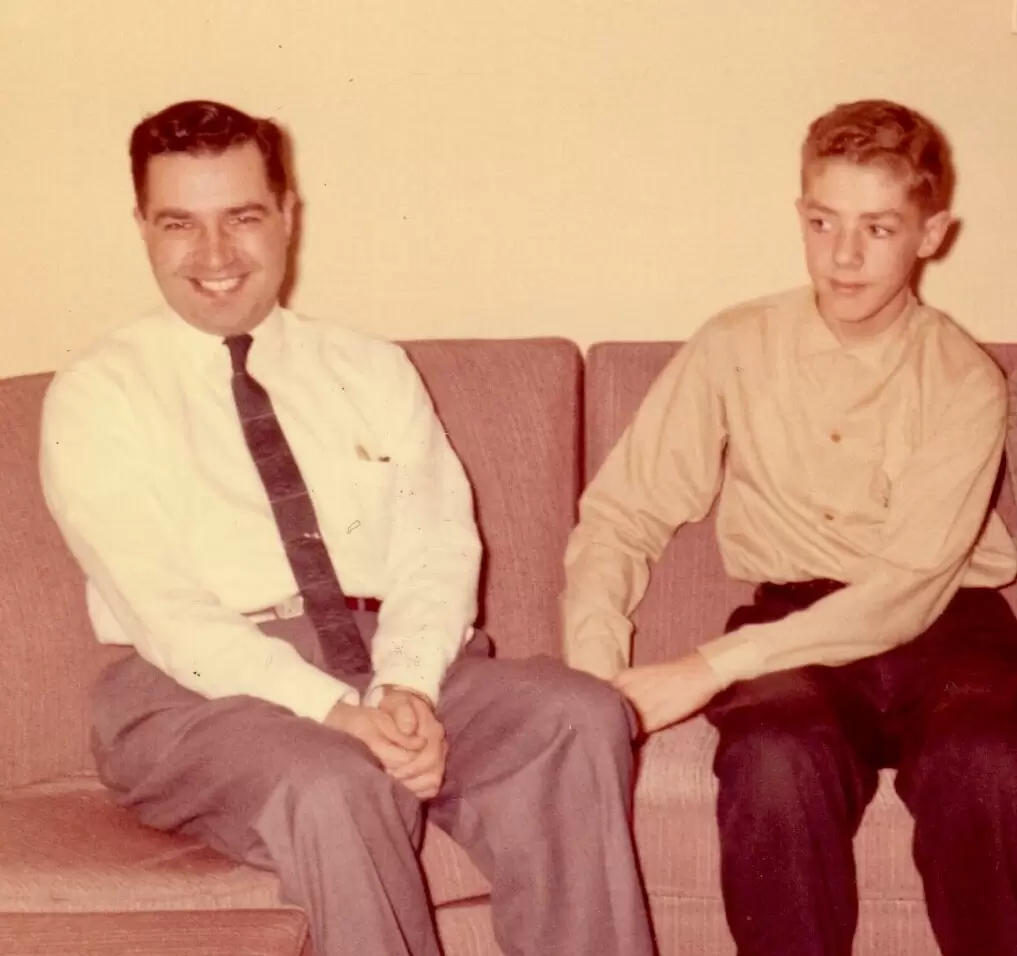

Lambert's early years were far, far away from the glamour of the Sunset Strip. He was born in Cudahy, Wisconsin in 1948 and graduated from Cudahy High School in 1966.

Checking the box

Bobby joined the Boar’s Head Singers, a choir at All Saints Cathedral on Milwaukee’s East Side. This was his first small step towards coming out. He made many new friends, including Jeffrey Dooley, a high school dropout who became a professional singer in New York City, and Margaret Hawkins, the choral director of the Milwaukee Symphony.

“Jeffrey was gay and everyone around him was gay. That’s how I met my first boyfriend, and how I became a music major. Boar’s Head had a hand letter press and created these incredible programs with beautiful illustrations. I still have some today in my archives.”

“Jeffrey was one of my favorite people in the world, and one of the people I modeled myself on.”

Starting college at UWM, he was introduced to UWM educator Barbara Gibson by a high school friend.

“Barbara was just great,” he said. “She was already 40 years old, which was just stunning to us, because she was so open to new things. I signed up for her class and wrote a piece about coming out that she made me read to the class.”

“She really liked me, and thought I should meet her friend Jerry Dreva. And you know, when people say, you’ve got to meet my friend, that’s the last thing you want to do!”

It would be another year before he did.

The specter of the Vietnam War draft loomed large, pushing Lambert to make a life-altering decision.

"I wasn’t doing well in college, and faced losing my student deferment,” he explained.

“The only way I could get out of the war was to check the box," he says, referring to declaring his homosexuality. In that era, it was a move that carried severe social consequences.

"Once you check that box, you’d outed yourself. Since this information was public, your life as you knew it was over. It was NOT an easy out. As a homosexual, your only future would be as a hairdresser, florist, or decorator – and maybe not even that.”

“One of my high school friends got a job as an interior designer at the Furniture Mart in Chicago. He was followed to a gay bar and fired the next day.”

“Once I gave it all away, I had no limits anymore. There wasn’t anything to be afraid of. There was a revolution coming."

"And what was the point of finishing college anyway, if no one would employ me?”

Life without limits

Embracing his newfound freedom, without school or career goals, Lambert embarked on a three-month European adventure with a high school friend, where a near-death experience in Malaga served as a catalyst for a life lived without restraint. Sleeping overnight in his vehicle, he nearly succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning.

"If this can be over this quickly, there's no reason not to do everything I want to do," he resolved.

“Returning to Milwaukee, I got back in touch with Barbara Gibson. She showed me a piece that Dreva had done, a little hand-made art project, hand stamped with EGO POEM on the front, a Xerox collage and poem inside. I was intrigued, and she again proposed we meet."

"But Jerry was suspicious – and it was arranged that I meet his boyfriend Ben over dinner to check me out. Ben recalls that I made Cornish game hens. In any case, I passed the test.”

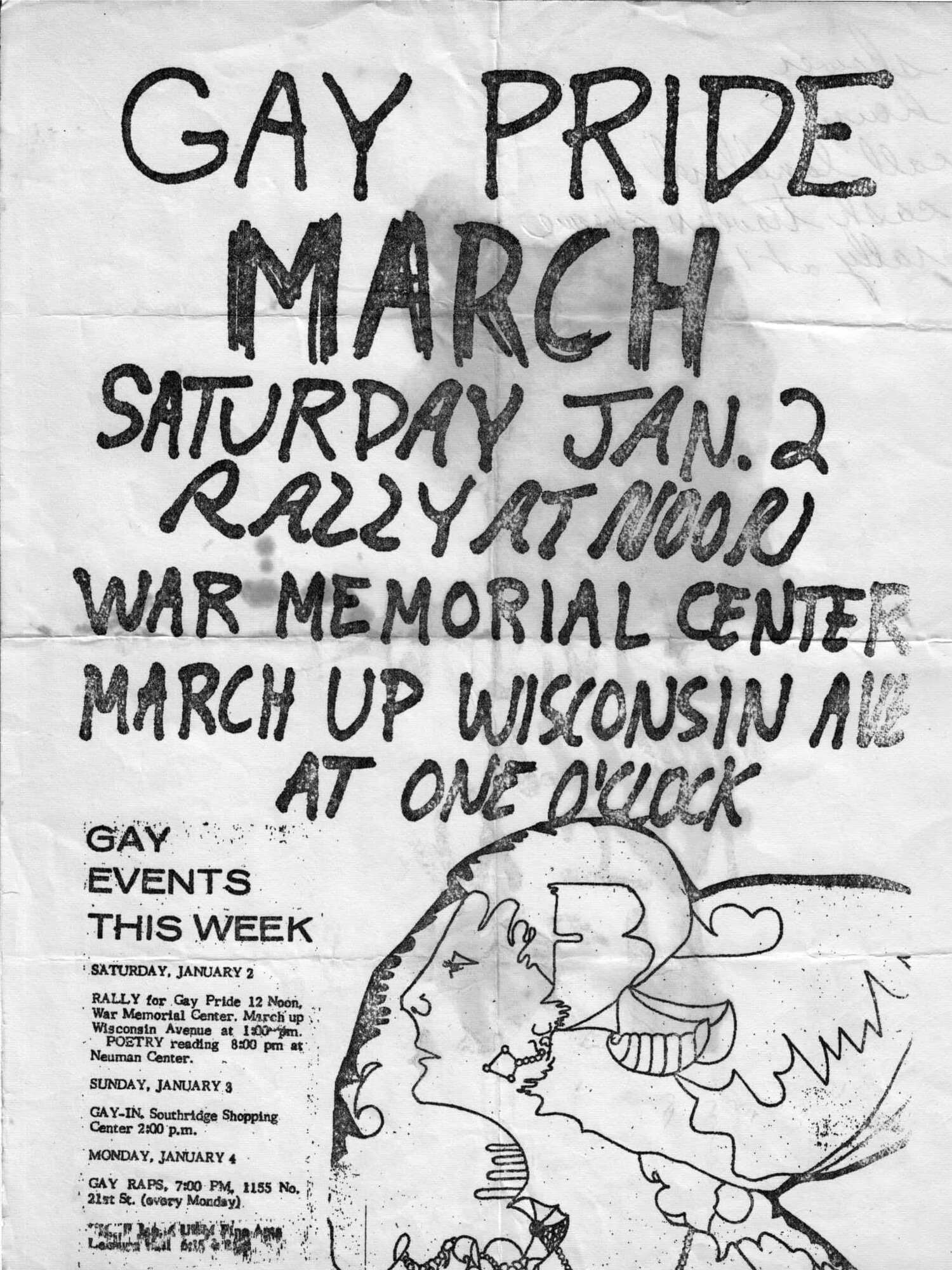

“Thus placated, Jerry and I agreed to meet at an upcoming march being planned. We greeted each other in the lobby of the War Memorial Center at the appointed time, he in a long black leather coat, and being warned of my aversion to politics, said with sarcasm, as he scanned the motley assembly, ‘well, here’s the movement. What do you think?”

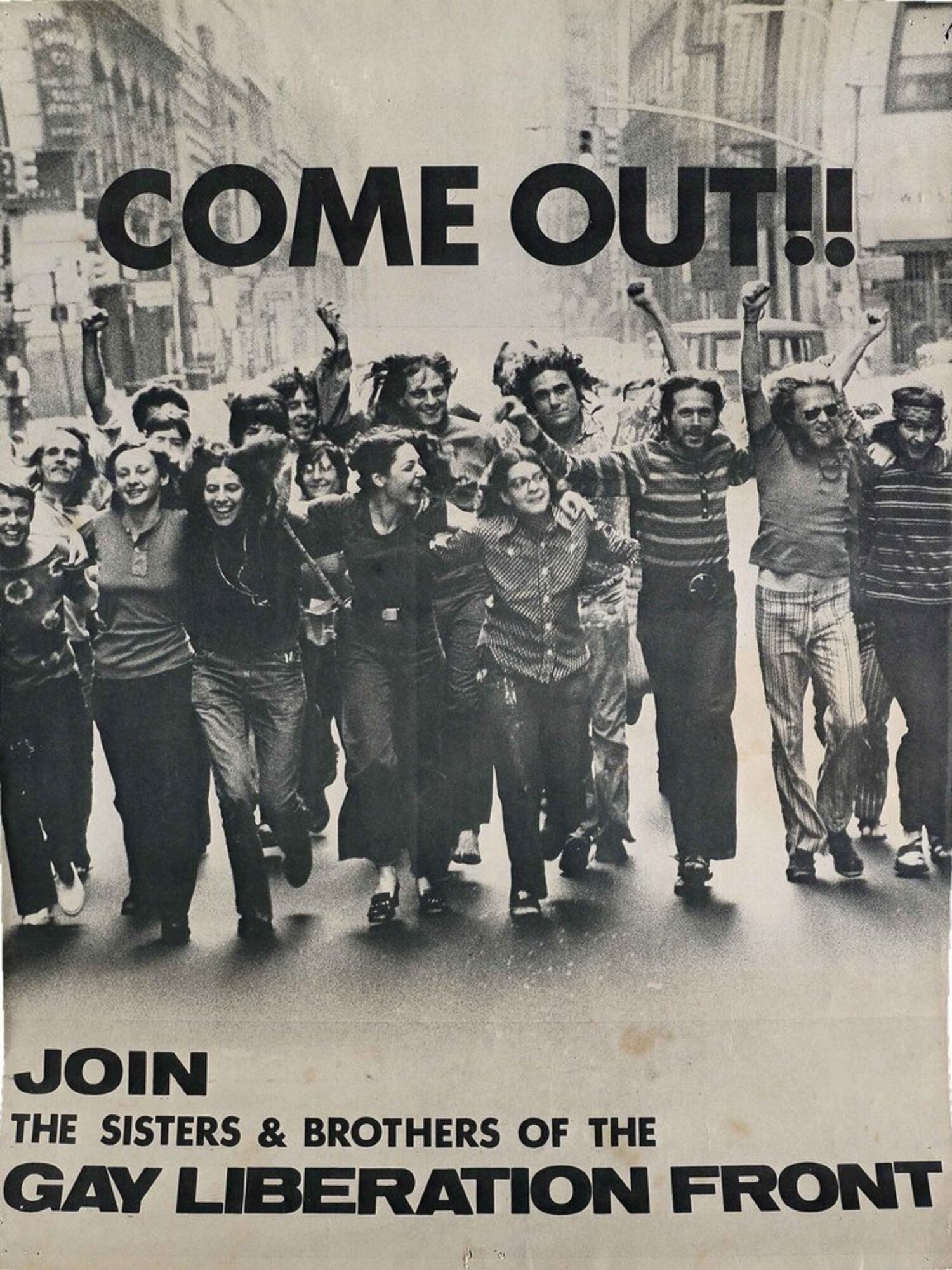

Moments later, they joined 24 others and marched in the state’s first pride march on January 2, 1971, powered by Gay Liberation Front and documented by Kaleidoscope Magazine.

“We stormed into a Marine recruiting center, on 2nd between Wisconsin and Wells, shouting slogans, and I’ll never forget the look on that officer’s face: not anger, just slack-jawed astonishment. It was a stunning lesson in the power of actions and words.”

GLO was Milwaukee's first organized queer resistance (1970.)

GLO was Milwaukee's first organized queer resistance (1970.)

After a few months, GLF splintered from GLO to take a more radical approach. (1970)

After a few months, GLF splintered from GLO to take a more radical approach. (1970)

Wisconsin's first pride march was on January 2, 1971.

Wisconsin's first pride march was on January 2, 1971.

The Bon Bons cometh

After meeting Dreva, the trajectory of Bobby’s life changed forever.

“Jerry and Ben had been living with the Gibsons, but when that household dissolved, Ben left for New York the day after the march and Jery returned to his parents’ house in South Milwaukee, as I was with mine in nearby Cudahy.”

“When Ben left, Jerry realized he needed me, because he didn’t drive, and I had a car,” laughed Bobby. “I think now he knew he would have to teach me to be the person he wanted ot spend time with, and that I was good raw material.”

Thus began an education, friendship, and collaboration that would span another 25 years.

In the early 1970s, Lambert, Dreva, and friends found themselves at the heart of a queer cultural revolution in Milwaukee.

“Jerry connected me to his political friends and associations, but as gay rights pioneers, we both realized the limits of such structured organizations, and thought we could find more effective strategies.”

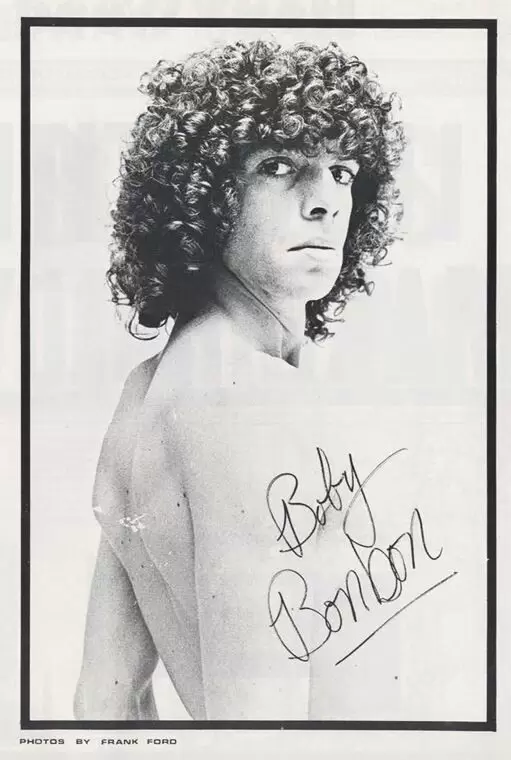

The first move away from that was the Radical Queens: Chuckie Betz, J.P., and Gary Pietrzak. Inspired by groups like The Cockettes, they moved even further waway, forming Les Petites Bon Bons, a collective that defied categorization. Jerry, as “Jeri BonBon,” and Bobby, as “Boby BonBon,” became the ringleaders of a brand new kind of circus.

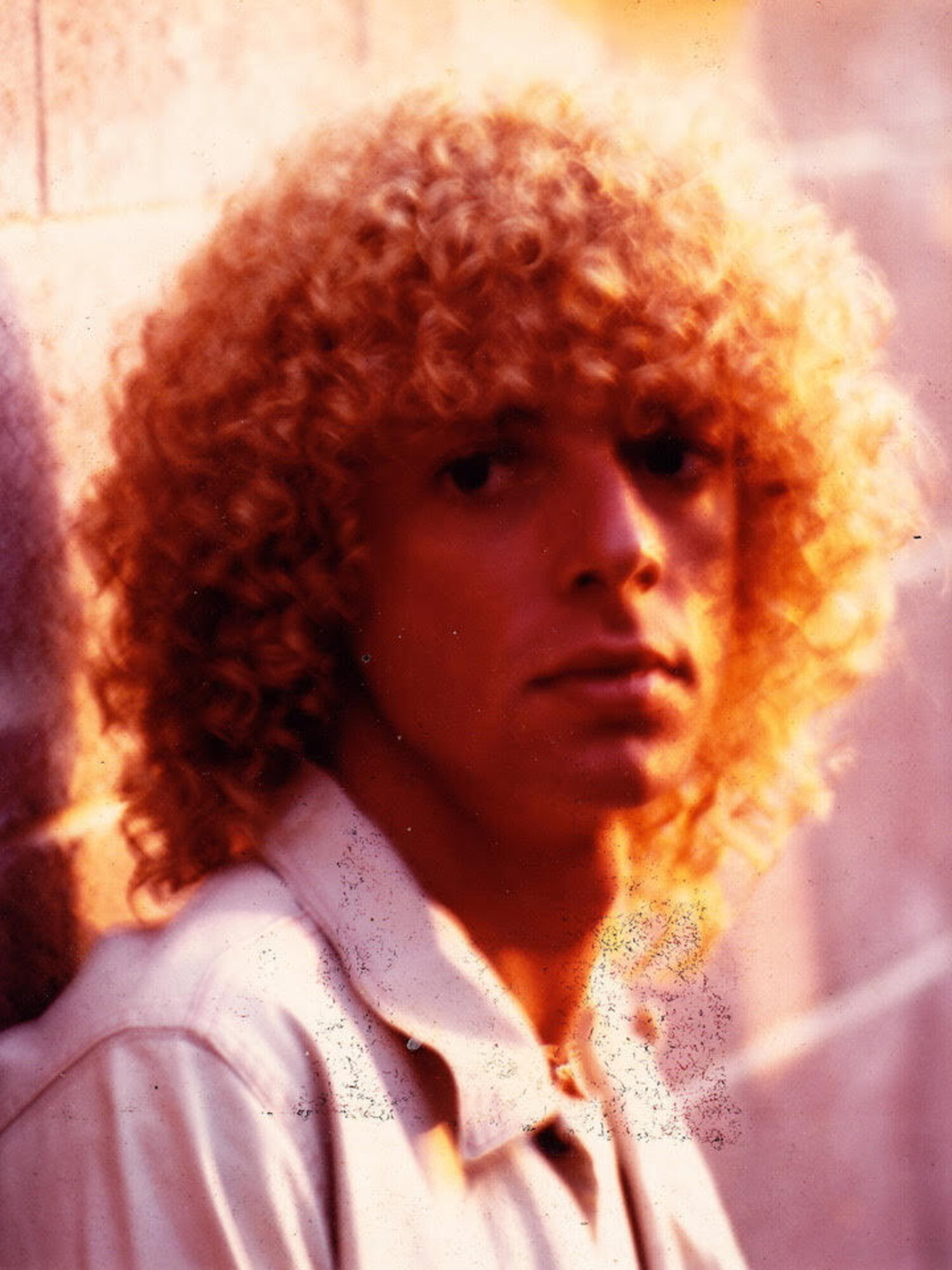

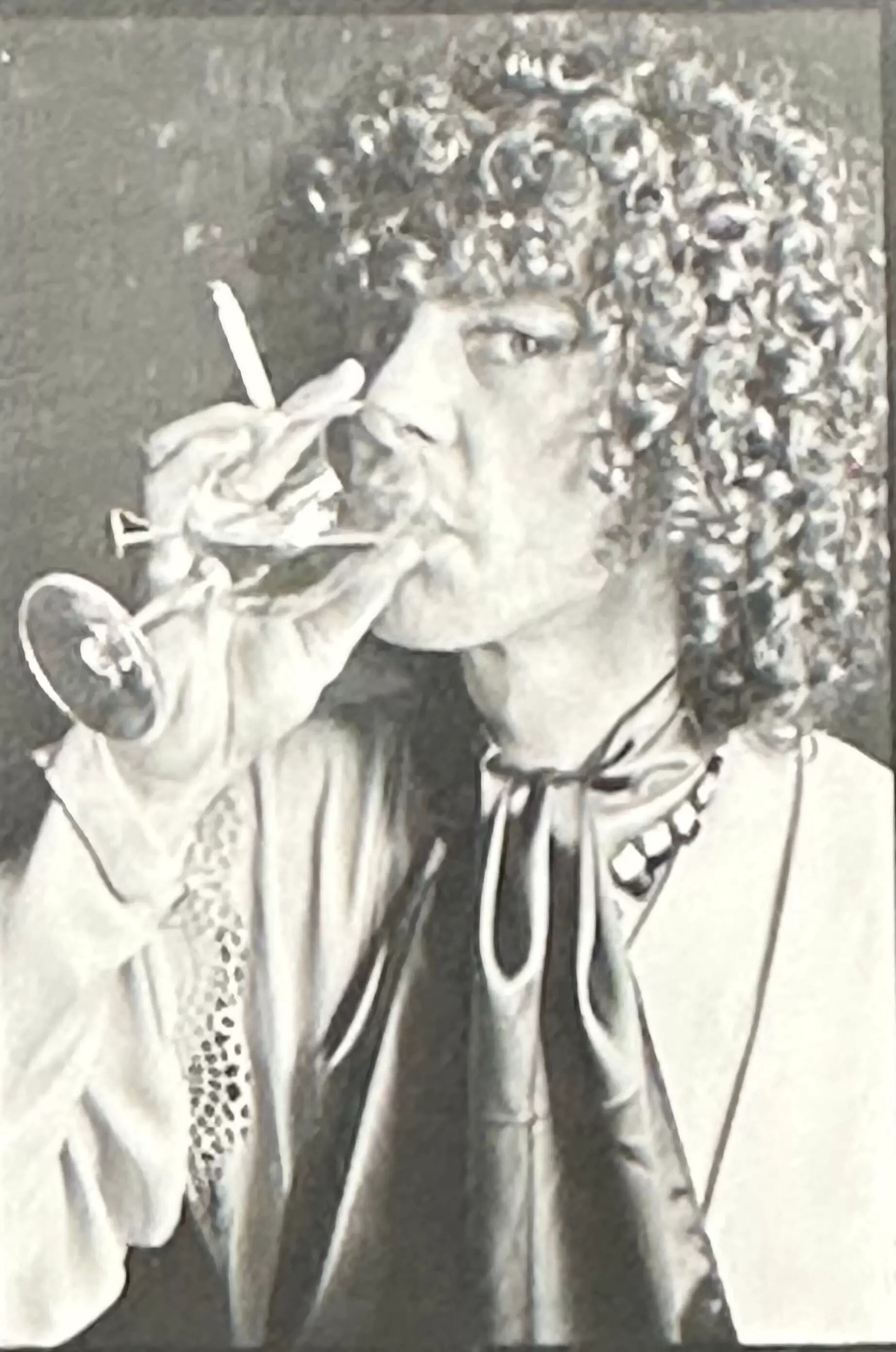

"We are poets, and we are dancers. Les Petites Bon Bons is the name of the play, a group of rock musicians, a gay twirling corps, a traveling circus," they declared. Following a Francis Ford studio shoot and art show, the Bon Bons now had professional photos to promote their cause.

The Bon Bons were a "group of gay life artists" who aimed to "sabotage seriousness" and "imagine a gay universe." Their art was their politics, their politics their love, and their lives a performance. They challenged societal norms with humor, irony, and a healthy dose of the outrageous.

"It was just outrageous what we could get away with," Lambert asserted. “Everything in life was so structured, and nobody ever questioned the structures. We found that if you moved outside the rigor, you could find all these little wormholes to make things happen.”

Their aesthetic was as groundbreaking as their philosophy. "Thrift shop hippie glamour met classic drag on an acid trip," Lambert recalls. The Bon Bons crafted a unique visual language that blended high and low culture, influencing fashion and art for years to come.

The Bon Bons used correspondence art as a weapon of cultural disruption, sending hand-crafted, often provocative packages to artists, musicians, and celebrities. Andy Warhol, William Burroughs, and David Bowie were among the many famous recipients of their artistic missives.

"We used the mail the way people use the internet now," Lambert explains. “We had access to anyone, and we could do anything. We were doing things nobody had ever done, and we knew we would go down in history in some way or another.:

"We knew our work would wind up in museums. We just didn’t think it would take 50 years.”

Les Petites Bon Bons (by Francis Ford)

Les Petites Bon Bons (by Francis Ford)

Boby BonBon, Jeri BonBon and friends: "This is Los Angeles"

Boby BonBon, Jeri BonBon and friends: "This is Los Angeles"

This is Los Angeles

But Milwaukee was too small to contain the growing crescendo.

Increasingly unhappy living at home, Jerry joined Ben at a collective on the lower east side of New York in spring 1972. After returning to Milwaukee for a few weeks, he followed Ben to his hometown, Los Angeles. Ben grew up in West Los Angeles, where he had classmates like “Lumpy” from Leave it to Beaver, and a friend named Richard Cromelin, now a rock writer for the LA Times and Rolling Stone.

Jerry Dreva left for Los Angeles on May 29, 1972, and suddenly found himself “smack in the middle” of the rock and roll scene upon arrival. He vowed to become the “most notorious male groupie” within one month. Through a seven-month series of hand-written letters, Jerry chronicled his California adventures to an increasingly envious Bobby.

“I was living with my parents in Cudahy,” said Bobby, “and working second shift at a paint roller factory for $1.35/hour. It was the worst job I ever had. To say my life stood in stark contrast to my own ideals, much less the letters coming from LA, would be an obvious and painful understatement. It was the only way I could make the money I needed to leave.”

The second shift schedule allowed Bobby to go out at quitting time, and he soon discovered a new East Side hangout, the Neptune Club (1100 E. Kane Pl.) which opened May 27, 1972. He met someone there that he’d spend the next 16 years with.

In January 1973, Bobby decided enough was enough. He quit his job, announced that he was moving to Los Angeles, and convinced his boyfriend to come with him.

“I was going – with or without him,” laughed Bobby. “I’m glad he chose to come with me.”

After a short stay in a Sunset Boulevard motel, they rented a house in Laurel Canyon for a year, owned by a former Western movie star, before buying a beautiful home in the hills above Mulholland Drive.

Bobby’s first night out was at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco. At one point, he was called out to the front of the club for photographs. Two weeks later, a photo appeared in Rock Magazine with the caption, “This is Los Angeles.” Mentions of the Bon Bons began to pop up in nightlife columns – while images of Jeri and Boby began to pop up everywhere.

“Oh, you pretty things, Miss Jeri and Miss Bobi of the Bon Bons make their Hollywood debut: girls, keep a close watch on your old man when these cuties come to town.”

Lambert and Dreva's courage knew no bounds. The Bon Bons became "artists in residence in the glitter scene, court jesters for rock and roll royalty." They infiltrated Hollywood, befriended rock stars, and threw legendary parties. Attending the Elton John "Yellow Brick Road" party at the Roxy, attended by the likes of Linda Lovelace and Paul Lynde, was a highlight of the era – and being hired by Columbia Records to throw a party for Iggy Pop became a defining moment in their careers.

Their influence reached far and wide. David Bowie was so inspired by Dreva's mailings that he incorporated elements into his "Ashes to Ashes" single cover.

The Bon Bons' time in the spotlight was marked by both triumph and turmoil, including a few close encounters with the law. Yet, they stayed committed to shattering the status quo.

"We were testing those kinds of limits, and more and more you just do it, and see what happens with a straight face," Lambert recalls. “Some of the Bon Bons talked about doing things that they never wound up doing. But Jerry and I actually did all the things we set forth to do.”

One of those things was Egozine, a three-issue subculture zine released between 1975 and 1978. Egozine has been featured in art exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, the Bibliothèque Kandinsky in Paris, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, Spain.

Beyond the Bon Bons

As the Bon Bons' fame grew, so did the challenges of maintaining their artistic integrity.

"As soon as people thought they knew us, we wanted nothing more than to destroy that notion," Lambert says. "We never wanted anyone to be right about who they thought we were. Our core philosophy had always been fluid identity.”

“We started using Yesterday’s Bon Bons, because the whole scene had gone punk. After all, we couldn’t go to The Outcast (a popular leather bar) in glitter.”

“Within two weeks, I completely changed, and I can see it in the photos. I cut off all my hair, changed my clothes, and started going to leather bars – only two weeks after my hair was big, wild, and bleach blonde.”

On October 2, 1973, Bobby wrote to a friend, “Strange things have been happening in my life and in my head… I have become totally disinterested in BB. To me, that era is completely over, dead of natural causes…I wear nothing but butch Levi and leather drag now… went to my first leather bar, and there were all the numbers I’d been looking for years.”

In 1976, Bobby Lambert left Los Angeles for Northern California. He continued to explore his artistic vision, connecting with like-minded artists like Genesis P-Orridge and Throbbing Gristle. and remaining a force in the avant-garde world.

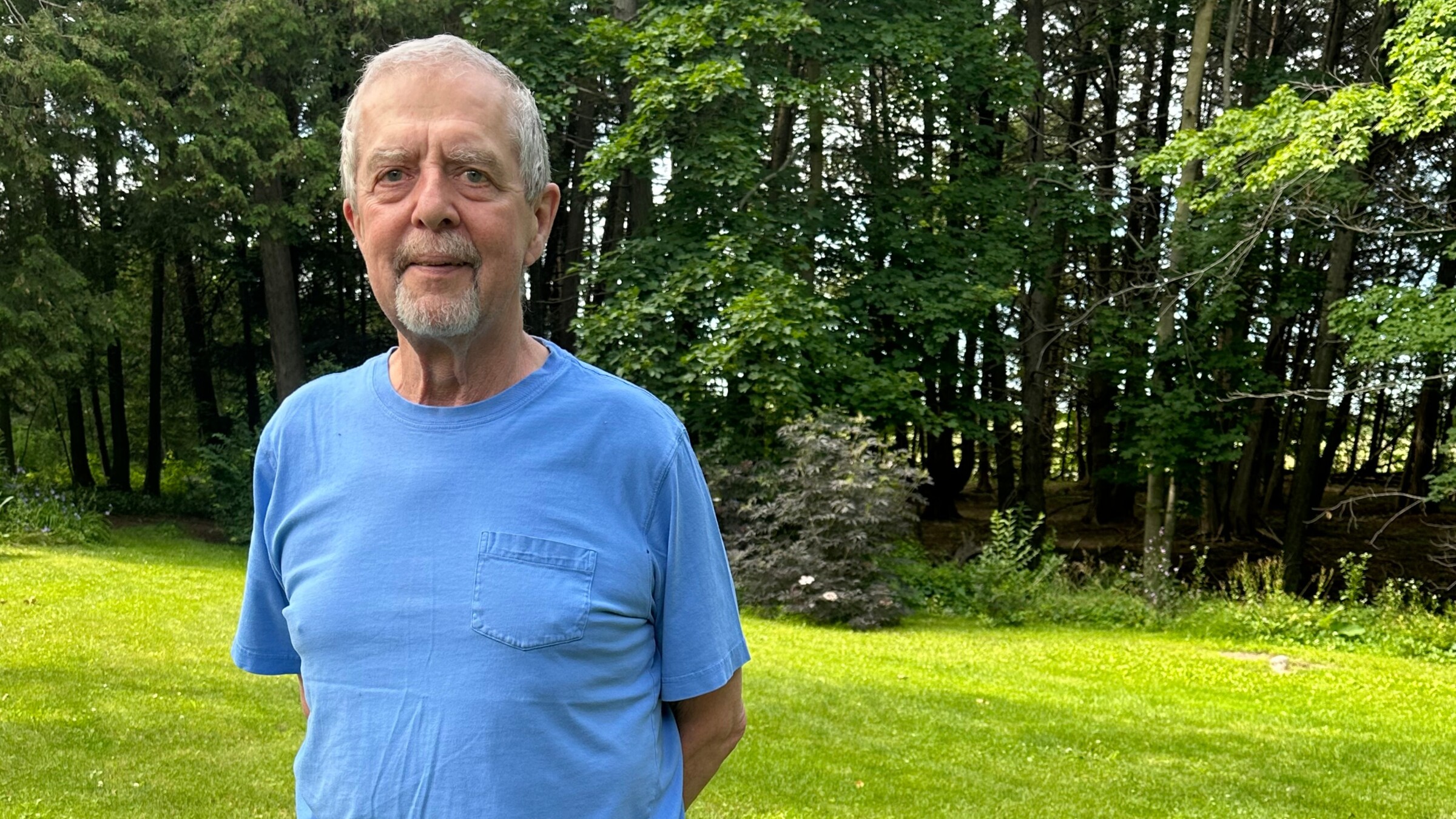

After 50 years in California, Lambert recently started a new chapter in northern Wisconsin. He has immersed himself in the local community, rebuilding a house and finding solace in the beauty and the people around him. Never one to slow down into retirement, Bobby is operating a thriving specialty foods business from his own backyard, using his grandmother's cherished family recipes.

"I'm happier than I've ever been in my life. Wisconsin is such a beautiful, beautiful place."

Looking back on his extraordinary life, Lambert reflects on the Bon Bons' long-term impact.

"We created access to self-representation, to self-mythologizing, to creating a sense of self, at a time when the average person neither had nor expected to have access to any of that,” he said. “What we did was far more interesting than today’s reality shows, because we were aware of the artificiality of what we were doing. We were playing it, so we didn’t take it seriously.”

The Bon Bons were celebrated in the 2024 Pet Shop Boys song, A New Bohemia.

After decades of curating the Bon Bons archive, Bobby has entrusted his collection to Johan Kugelberg, a cultural historian, creator, and author in New York City. These strategic decisions ensure these artifacts will be safe for future generations.

“When Jerry Dreva died in 1997, forty boxes of original artwork was lost forever,” said Bobby. “His survivors picked the bones of his prized possessions and threw away anything they didn’t see as valuable. Since most of his content was countercultural, it went right into the dumpster.”

Robert Lambert's story is a testament to the power of art, activism, and the audacity to be true to oneself. By daring to challenge the oppressive conformity of the 1970s, he created a lasting legacy that continues to provoke and inspire activism today.

Bobby Lambert

Bobby Lambert

Bobby with fellow Old Eastsider, Peter Mortensen (2025)

Bobby with fellow Old Eastsider, Peter Mortensen (2025)

Bobby Lambert (2024)

Bobby Lambert (2024)

recent blog posts

February 25, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 24, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 21, 2026 | Meghan Parsche

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.