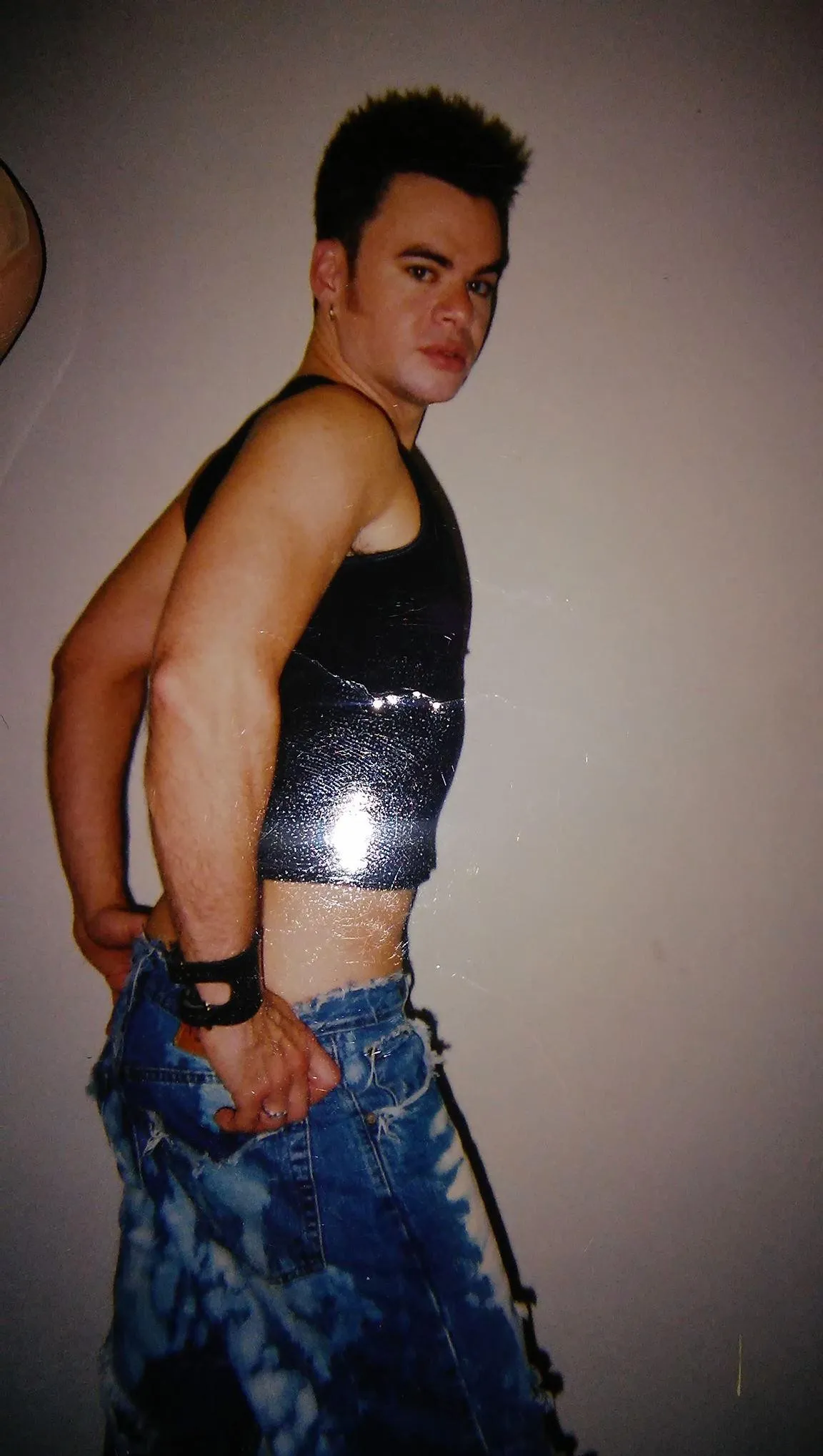

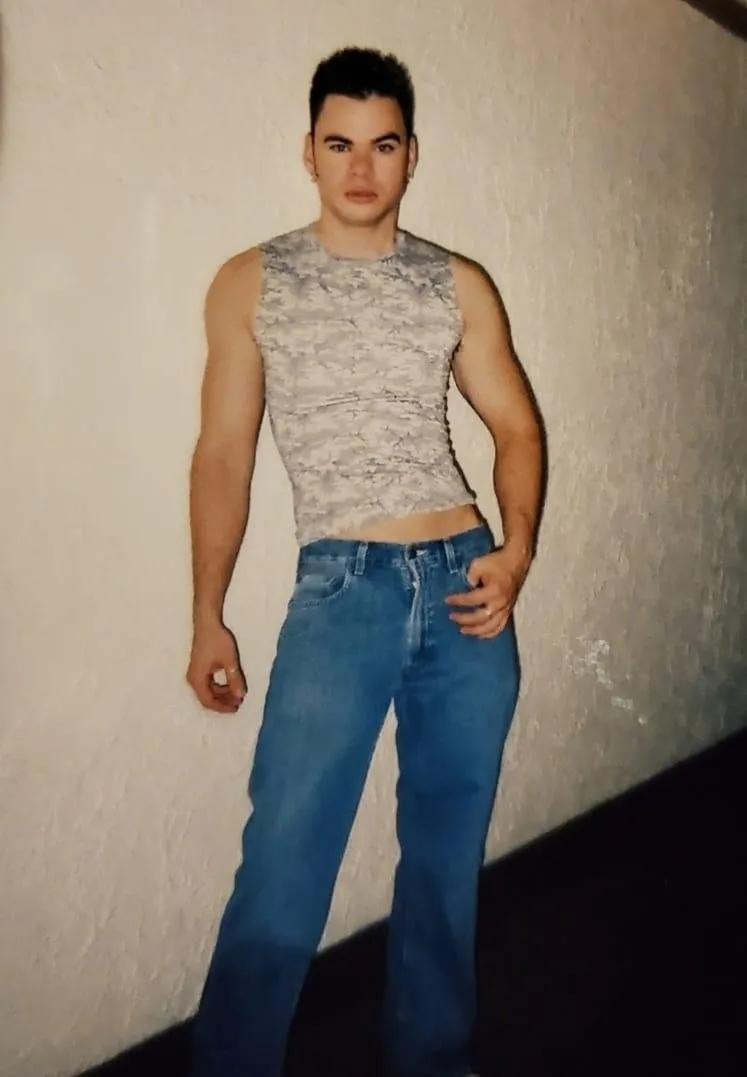

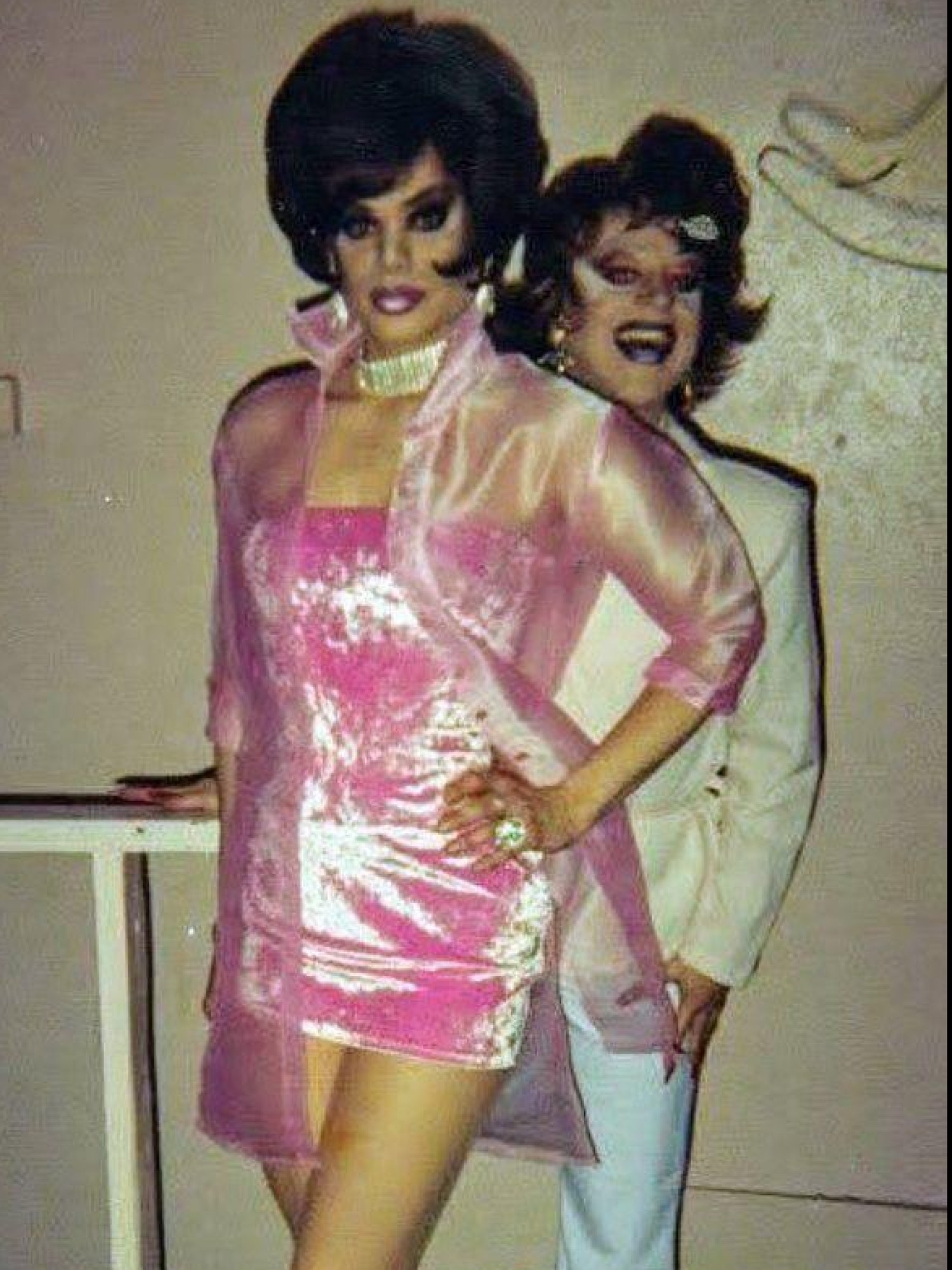

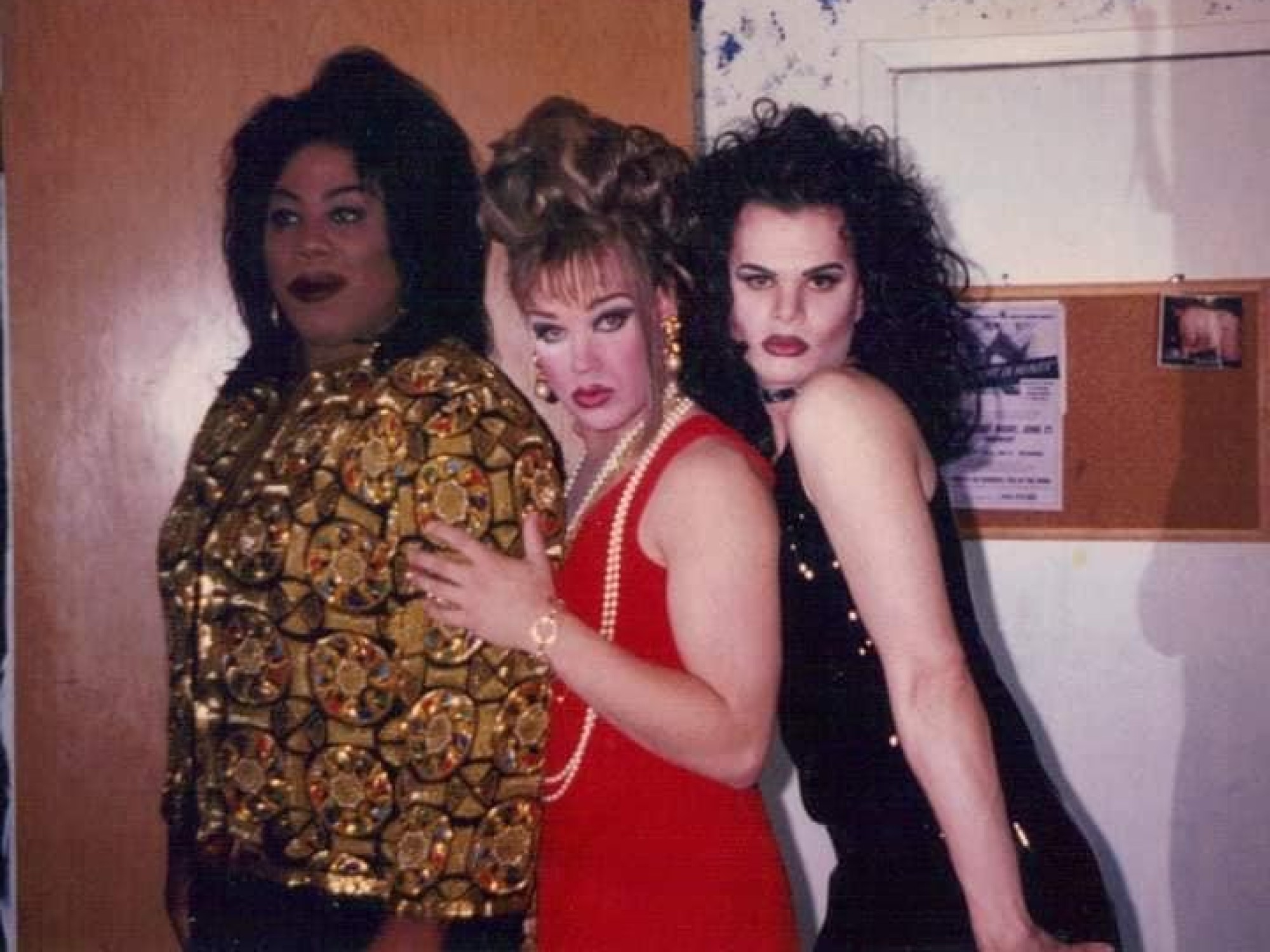

Shawn Wandahsega: causing a commotion with confrontational drag

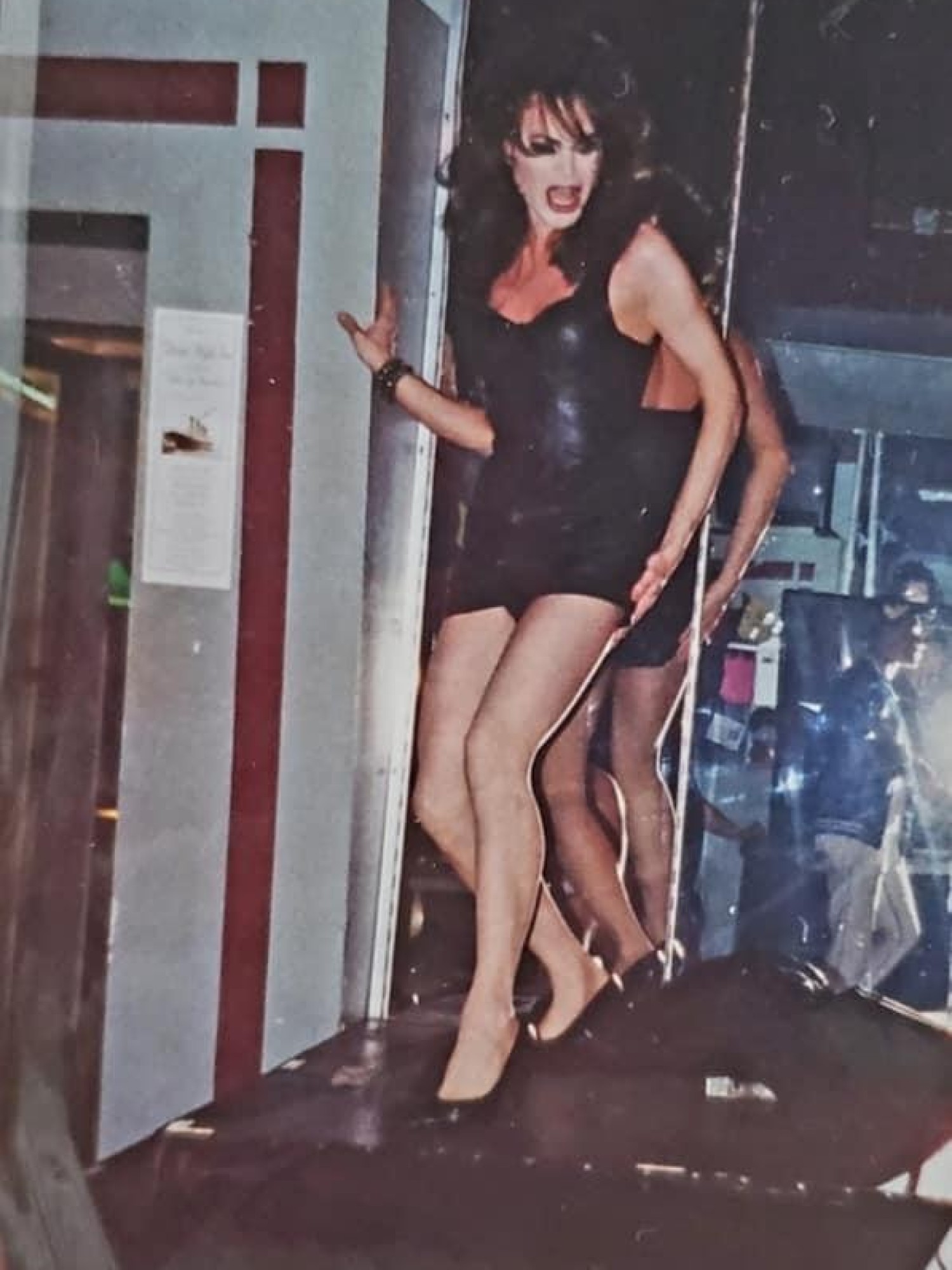

“I realized that I could say and do things onstage that I couldn’t do as Shawn -- so I kept pushing the limits to see what Shawna could get away with."

In the early 1990s, the windows of the Jean Nicole store on Wisconsin Avenue in downtown Milwaukee were impeccable. The mannequins were perfectly decked out in the latest fashions, beckoning to shoppers in the booming Grand Avenue Mall. They were the work of a young visual merchandiser named Shawn, who knew exactly when to dress them and how to capture the feel of the moment. But those mannequins held a secret.

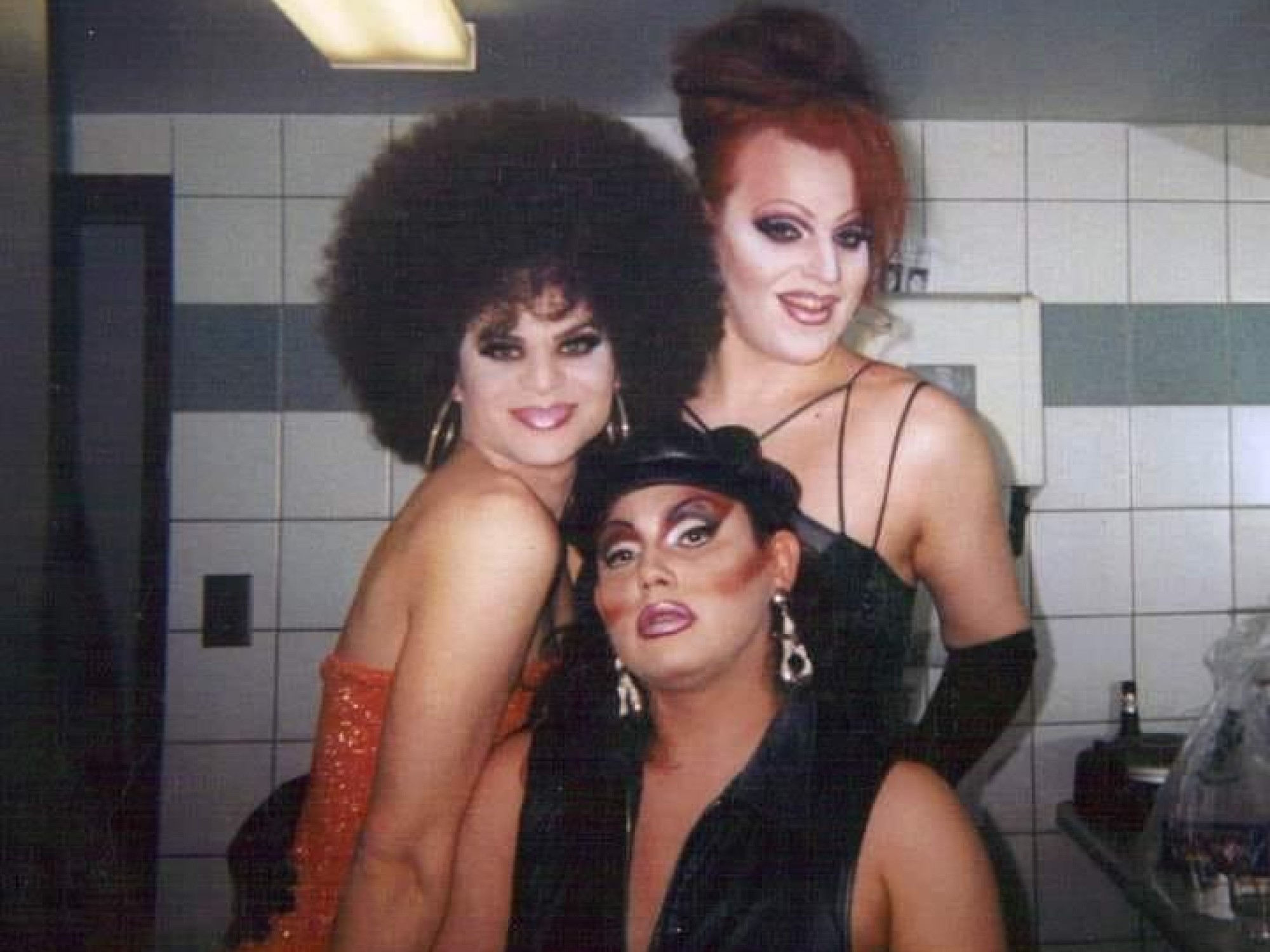

Shawn was young, broke, and hungry for a life that didn’t yet fully exist. By day, she pinned fabrics and adjusted limbs. By night, she was transforming into a creature of the Milwaukee night, an emerging drag performer in a scene that demanded glamour even if your bank account screamed poverty.

“I was really poor back then, so I couldn’t really afford wigs,” Shawn recalled with a mischievous laugh. “So, I’d take the wigs off the mannequins. I’d wear them to the gigs on the weekends, and I’d put them back on the mannequins’ heads when I got back on Mondays.”

The plastic women of Jean Nicole didn’t mind spending Sunday night bald, or sporting a temporary pixie cut while Shawn took their long, flowing locks to a stage at Club 219. It was a hustle born of necessity, a small theft of identity to fuel the creation of a new one.

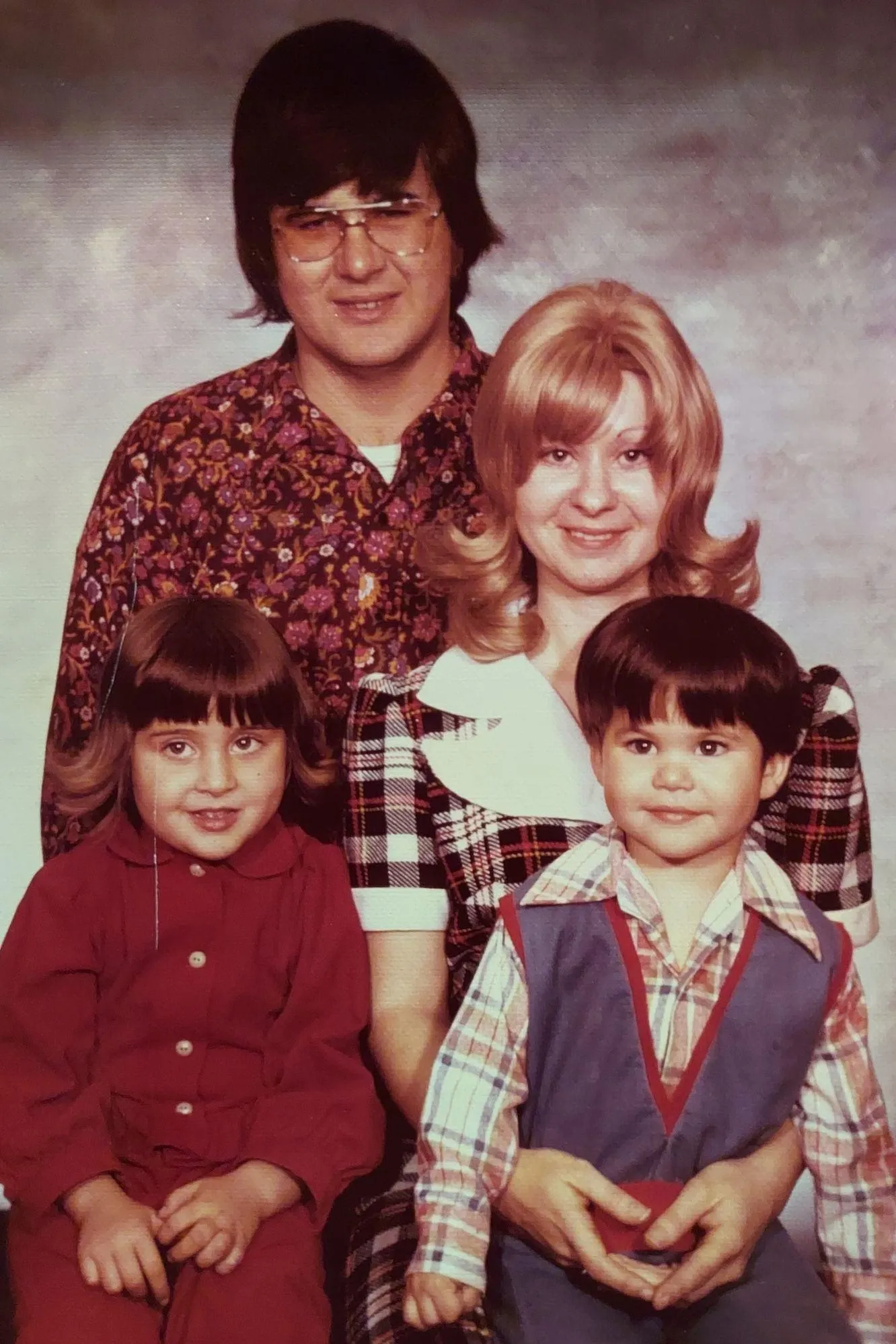

“It was always frowned upon from her… it was always like, ‘those damn Indians’ or ‘those damn rednecks.’”

Shawn lived in the friction between these worlds. He identifies deeply with the film Imitation of Life, seeing his own story reflected in the character who passes for white to escape the systemic oppression of her Black identity.

“I was always kind of trying to hide that I was Native American when I was growing up because it was so frowned upon by white people,” he admits. “I’m passing, so it kind of comes and goes, but you never, ever, really can forget who you are.”

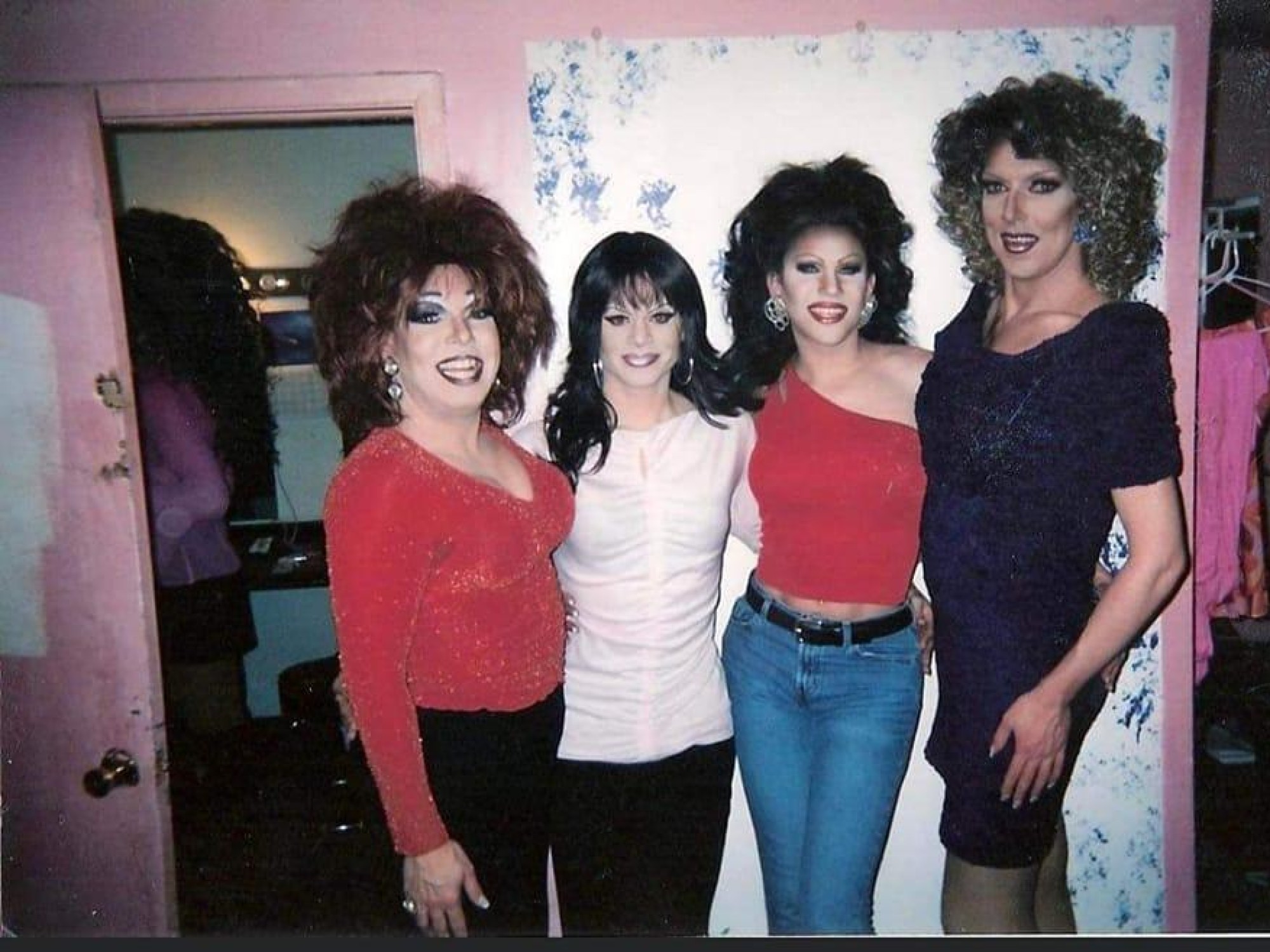

He sees a generation of younger queens who have it "easier” with Instagram fame, dozens of Wisconsin drag venues to choose from, bookings now based on demand and not talent, freedom from the old-school pageant system that used to make and break a girl’s worth. But he’s also mourning a loss of community. The fierce sisterhood of his youth has been replaced by an “every girl for themselves” mindset.

“And there’s so much infighting,” he said. “There’s a new drama every other day. It hurts us all.”

Yet, Shawn refuses to be a relic. At 55, he is still reinventing, still pushing, still pulling stunts. He knows that in a youth-obsessed culture, an older queen must fight twice as hard to remain relevant.

This fight culminated in a recent performance at PrideFest that Shawn counts among his top three moments of all time. He walked out onto the stage to perform Gloria Gaynor’s anthem "I Will Survive," but with a twist. He made it a political statement: "F*ck Trump."

He has built a rich life out of the scraps he was given in Gladstone. From the reservation to the runway, Shawn Wandahsega has walked a path paved with broken glass and sequins. Shawna Love is still booking shows, still gluing down wigs (now bought, not stolen), still demanding all the smoke and all the spotlight, and still causing a commotion.

And he’s nowhere near the end of his story.

Shawna Love is nominated as a Legend of Drag in the 2026 Wisconsin Drag Awards.

recent blog posts

February 25, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 24, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 21, 2026 | Meghan Parsche

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.