Unforgettable: Jason Doemel

"He wasn’t asking for approval, he wasn’t asking for acceptance, and he wasn't trying to fit in. And that pissed people off."

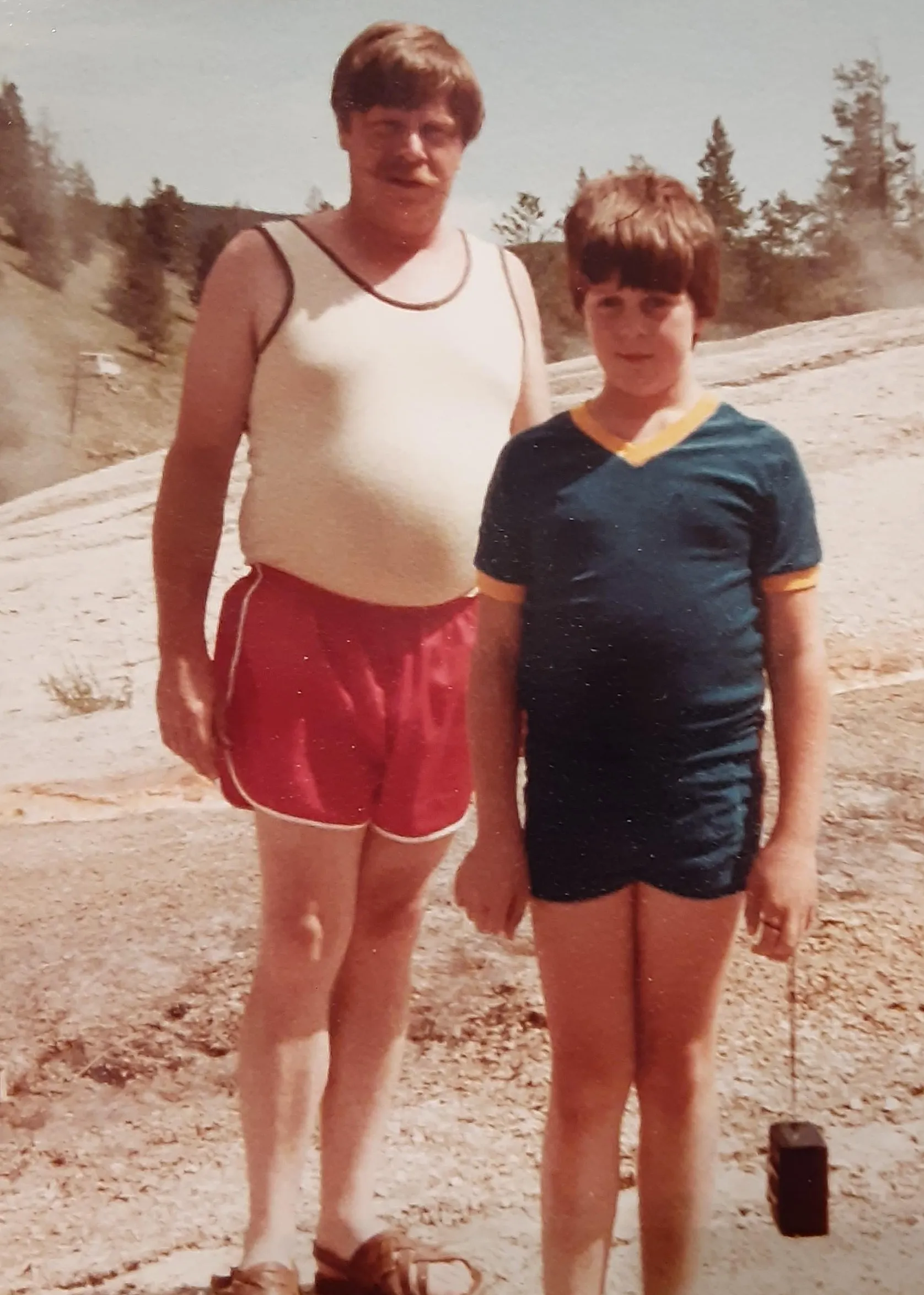

Jason was born January 27, 1973, in Oshkosh to Suzanne and Dale Doemel (1943-2021.)

“Dale worked at Derksen’s Tobacco in Oshkosh. He was hoping Jason would be born on his birthday, but he wasn’t born until the 27th. This was our first indication that Jason was on his own schedule. Dale drew the photo for the birth announcement while we were at the hospital. People laughed because the baby boy had a cigar in his mouth.”

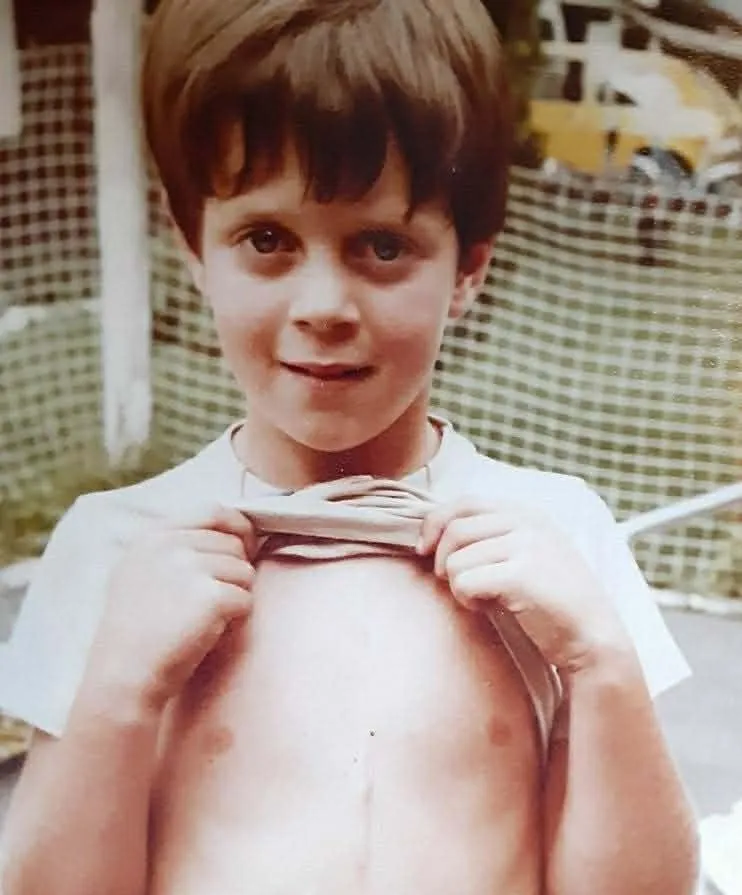

Jason had open heart surgery when he was only five years old, and he was always proud of his scars.

He had two younger brothers, Jeremy and Jonathan.

“Having a brother like Jason was a real experience for them,” said Suzanne.

“Frenchy didn’t care how old we were, as long as we signed a lease, paid our security, and paid our rent,” said Danielle. “I don’t remember anyone needing a parent to sign the lease for them. There were no background checks, no credit scores."

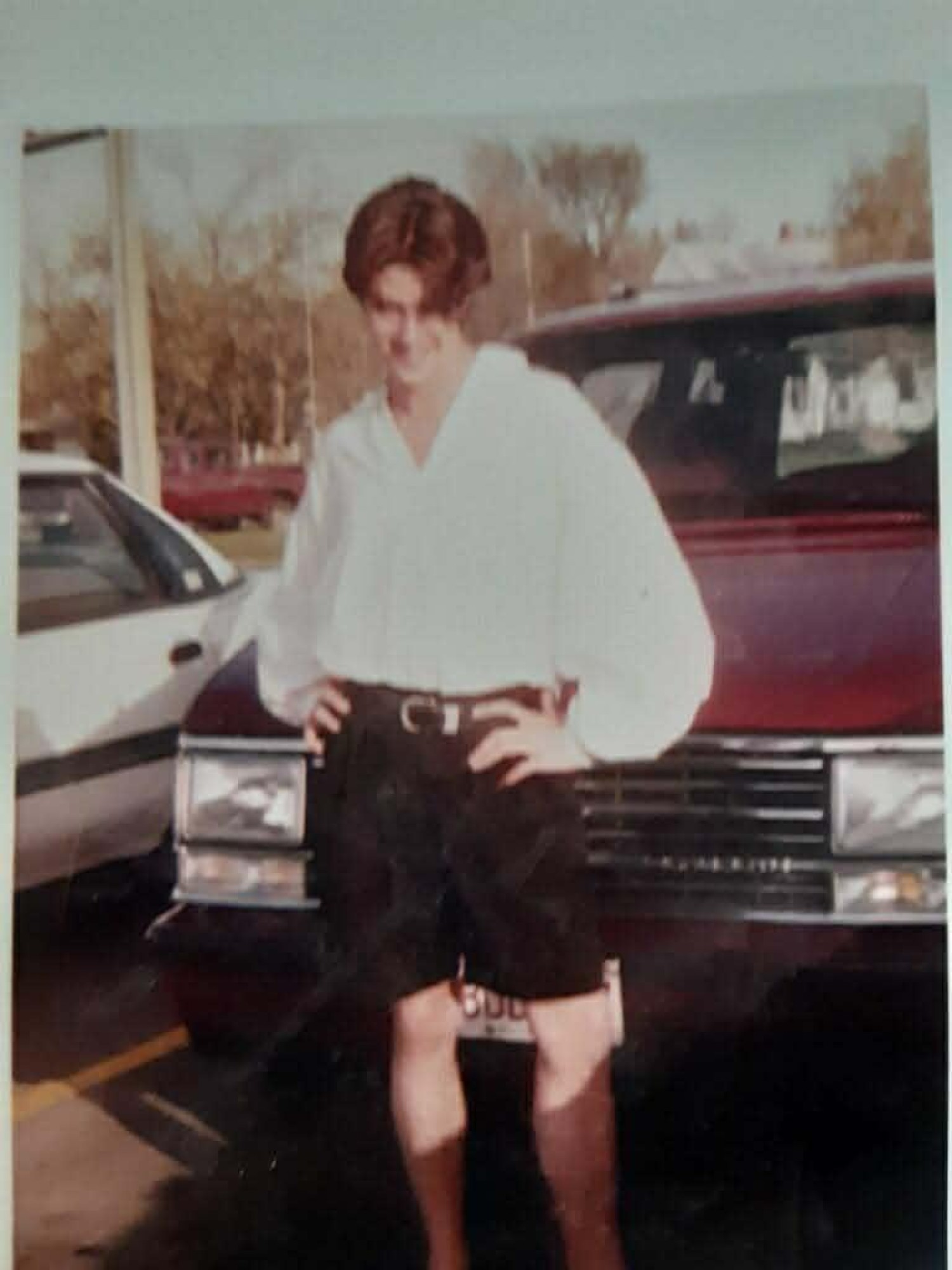

"It was just a free for all. We were both underage, living on our own, and going out all the time.”

Later, Danielle and Jason moved to the Norman Flats (626 W. Wisconsin Ave.) next door, where they shared a $325/month apartment with a third roommate. The Norman, already 100 years old, was known as a headquarters of creative, artistic, and eccentric counterculture.

“In summer 1990, I was left behind by a friend at Club Marilyn, and I walked over to Jason’s to stay overnight,” said Eric. “I remember visiting him for New Year’s Eve and staying out until 6 a.m. Later, he came to visit me in Minneapolis.”

Milwaukee wasn’t always kind to Jason. He was jumped on his way home from the Pfister. He was attacked on the way home from Grand Avenue. He was mugged by skinheads. He was assaulted by an angry neighbor at the Norman. He faced backstabbing and betrayal from cruel classmates he thought were his friends.

“He constantly had black eyes,” said Danielle. “It breaks my heart to think about it.”

And his apartment – along with all his possessions, his artwork, and even his cat – was destroyed in a five-alarm fire on January 12, 1991.

“He got out of the Norman Building wearing only a robe in the middle of winter,” said Suzanne. “Four people died in that fire. He very easily could have been one of them.”

Jason went over to Dunkin’ Donuts on 7th and Wisconsin for shelter. However, they asked him buy something or leave. He was given snow pants and a coat by some of the unhoused people he knew from the neighborhood.

“He paid it forward, and it always came back to him.”

“He never suffered the poor me syndrome,” said Jeremy. “He never had a victim mentality. He was never pissed at the world. His only frustration, really, was get out of my way and let me live.”

“I sometimes got the impression that Jason always knew he wasn’t long for the world, so he wanted to pack in as much life as he could live as possible,” said Danielle. "Sometimes he lived recklessly, dangerously, defiantly on the edge, and no one could convince him to change his mind."

While Jason didn’t graduate from Milwaukee Public Schools, he took correspondence courses through the International High School of the Americas to earn his diploma. Suzanne attempted to convince her school district – where she’d taught for decades – to give him a diploma.

“They wouldn’t do it,” said Suzanne. “This was my workplace, my school district, where I’d spent my career. And they still wouldn’t do it. Jason said to let it go. He said, ‘they don’t have any claim to my fame.’ He got over it faster than I did. But I don’t think I ever really got over that.”

"Jason wanted to be loved very, very badly," said Danielle. "He wanted someone to love in return. He fell in love with a gentleman named Gabby from the Quad Cities. I don’t know whatever happened to him. I’m not sure the relationship ever lived up to Jason’s expectations, and it broke his heart. It was just more hurt and more anger for him to process.”

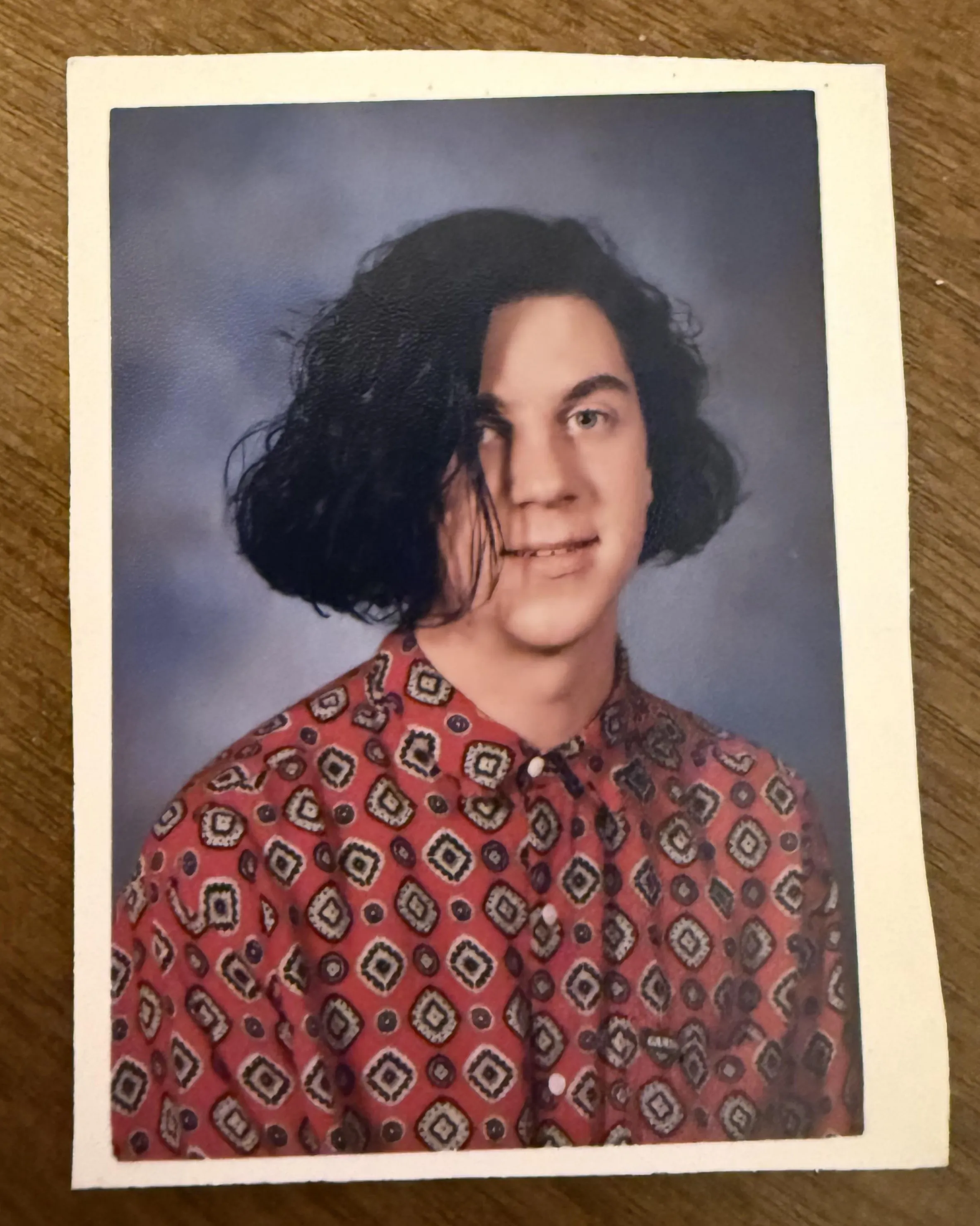

“I think Jason learned that people pleasing only led to suffering, so he carried himself in an authentic, honest and vulnerable way. Most people are afraid to be that bold," said Jon. “I know that really agitated people: the fact he wasn’t asking for acceptance, he wasn’t asking to fit in, he wasn’t going to be helpless. And he exuded it to the point where he pissed people off. They’d try to oppress him, shut him down, scare him off. And he just wouldn’t back down.”

“Jason had no filter,” said Danielle. “He would talk back to dangerous people. He wasn’t afraid of anyone or anything. It was scary, because you wouldn’t know if these people were carrying weapons, or if they’d get violent with us. I remember telling him, this can’t keep on happening.”

After high school, Jason moved frequently around the country, from Los Angeles to Oregon to Madison to New Orleans, where the family visited him.

“When he was living in New Orleans, he wrote a song for me – to the tune of ‘On Broadway’ – as a Mother’s Day gift,” said Suzanne. “I still cherish it today.”

They did keynote presentations, panel discussions, and community outreach at colleges, schools, and town halls over the next few years. They were also invited to share their story at the International Council of Death and Dying in Chicago.

Together, they did much to change hearts and minds about HIV/AIDS locally and regionally.

“Few eyes stay dry when Jeremy and Jon Doemel speak about their brother,” said the Oshkosh Northwestern on March 27, 1998.

“For the two Oshkosh brothers, it means Jason will live on.”

“Jason’s legacy is that we shouldn’t judge what we don’t understand,” said Jon. “We shouldn’t villainize people in advance of a crime. Protecting someone’s emotional integrity is important. The fact is, HIV and AIDS are something that affected and are still affecting all human beings – not just gay men.”

“Losing Jason really broke some of his friends,” said Danielle. “Some of them never fully dealt with the loss, and some of them are gone now too.”

"Every time I hear his name, I wonder what kind of man he would be now. Would have found his love? Would he have found his peace? He never got to experience the things we did."

“Thank you for breathing new life into Jason's story,” said Danielle. “I want him to be remembered: good, bad, and in-between. I hope people realize that Jason never had the chance to be an adult. He was struggling to find safety for the entire time I knew him.”

Over 30 years after Jason’s passing, Suzanne still remembers her son’s tremendous love for life.

“Jason’s grandfather, who served in a World War overseas, always said that Jason lived much more in his 21 years of life than he ever had,” said Suzanne.

“And that’s how we will always remember him: as someone who truly and fully lived.”

recent blog posts

February 28, 2026 | Bjorn Olaf Nasett

February 28, 2026 | Michail Takach

February 25, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.