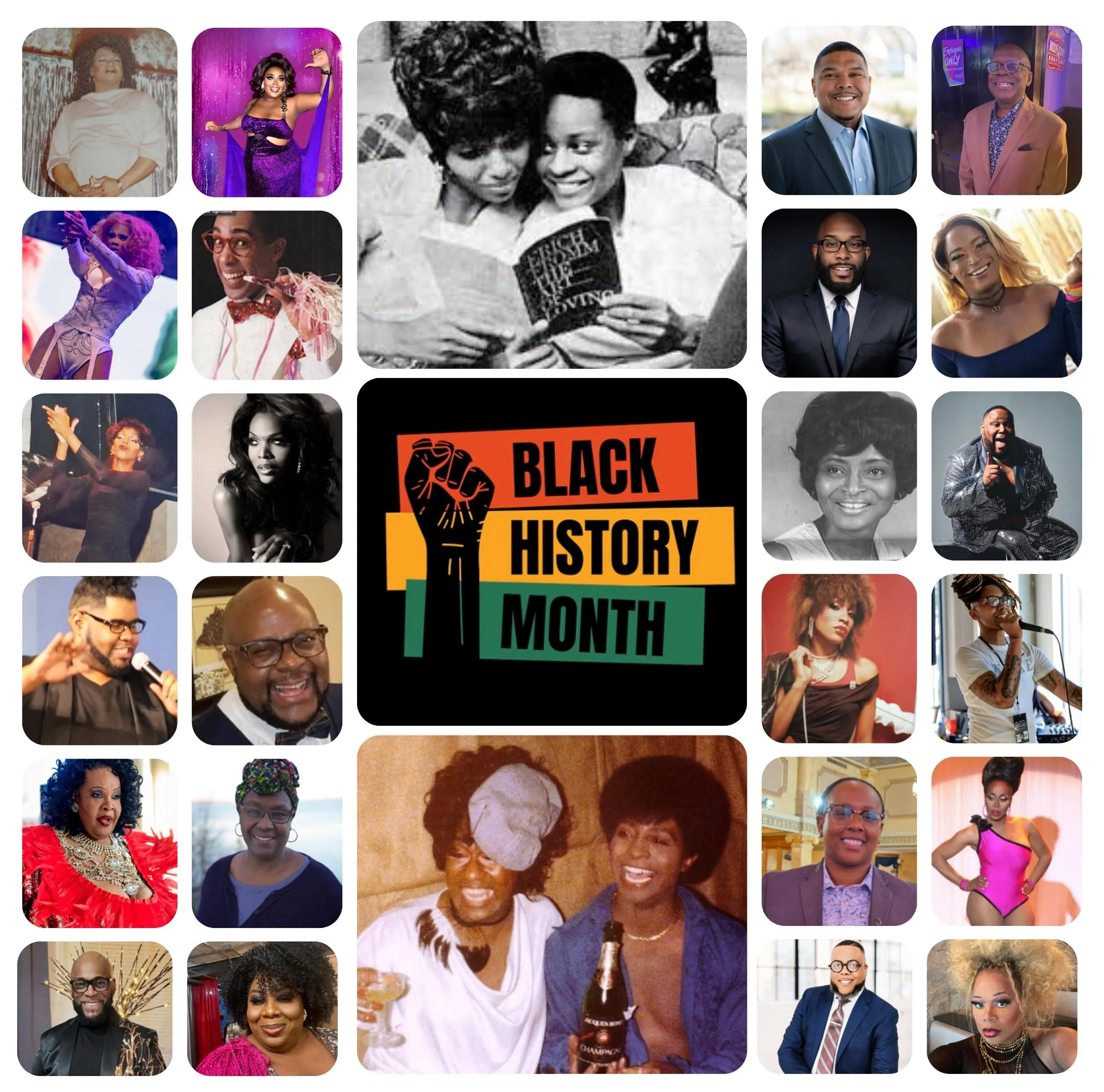

Celebrating the Black roots of queer liberation

Black History Month isn’t adjacent to LGBTQ history, it sits at its core.

It lives at the heart of our story, shaping its origins, fueling its resistance, and grounding its progress. The fight for queer and trans liberation did not grow on separate soil, it was nurtured in the same struggles for dignity, survival, and justice that many Black communities and leaders have long carried.

To understand LGBTQ history honestly is to recognize that Black history is not a parallel thread, it is part of the foundation that holds the entire narrative together.

You cannot tell the story of queer and trans liberation without telling the story of Black queer and trans people, not as side notes, not as supporting characters, but as architects. The movement didn’t simply make room for us. It moved because of us.

Modern LGBTQ resistance didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was pushed into being by people who were already fighting to survive at the intersection of racism, homophobia, and transphobia. Black queer and trans folks demanded dignity in a world that denied us humanity on multiple fronts and in doing so, we forced movements to grow wider, deeper, and more honest about what justice actually requires.

Take Bayard Rustin, for example, a Black Same Gender Loving (SGL) man whose fingerprints are all over one of the most defining moments in American history.

Rustin was the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. While others stood at the podium, he built the stage, planning, and orchestrating the logistics that brought more than 250,000 people to Washington, D.C. He worked alongside leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and A. Philip Randolph to make the march possible, the very gathering where Dr. King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

But Rustin’s impact didn’t stop at the march itself. His work helped expand the very idea of civil rights. He pushed the movement beyond a single issue affecting Black people into a broader fight for human dignity, one that reshaped what justice could look like in this country.

Because of that advocacy, civil rights became more than a struggle for one community. It became a framework for freedom that has opened doors for many across identities, across movements, across generations.

Whether we realize it or not, we’re all living in the ripple effects of that work, work that made it clear that freedom was never meant to be a single-issue fight.

Long before “intersectionality” became language, it was a lived reality. Black LGBTQ people understood that you cannot separate race from gender, sexuality from class, or identity from survival. Our lives made that truth impossible to ignore and our organizing reshaped how liberation movements think, act, and build to this day.

And this wasn’t just theory. It was survival.

Chosen family. Mutual aid. Community care. These weren’t trends or buzzwords, they were lifelines created by Black queer and trans communities who knew the world would not catch us if we fell. So we caught and continue to catch each other. And in doing so, we’ve created the models of care that still hold so many people today.

We’ve also refused to separate racial justice from queer liberation. We have understood that freedom doesn’t come in pieces and our fight continues to push movements to imagine something bigger than inclusion, we continue to demonstrate transformation because the work of our ancestors didn’t end in the past.

Black queer and trans people are still leading, organizing, creating culture, building safety where none exists, and dreaming futures where belonging is not conditional.

So for anyone committed to preserving LGBTQ history, honoring Black History Month is not a gesture. It is a responsibility.

Preservation means telling the truth, even when history tries to bury it. It means refusing erasure. It means documenting the full story, including the voices that were pushed to the margins but never stopped shaping the center.

Because protecting LGBTQ history means protecting Black history, queer freedom didn’t grow in a vacuum. It grew out of Black struggle, Black brilliance, and Black refusal to be silent.

Without Black history, there is no LGBTQ history.

Much of the freedom we claim today was set in motion by Black queer ancestors who chose to live boldly in a world that tried to erase them, who fought, created, loved, organized, and resisted anyway.

They weren’t simply part of our movements.

They built them.

Ricardo D. Wynn currently serves as the vice-president of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project.

Read More