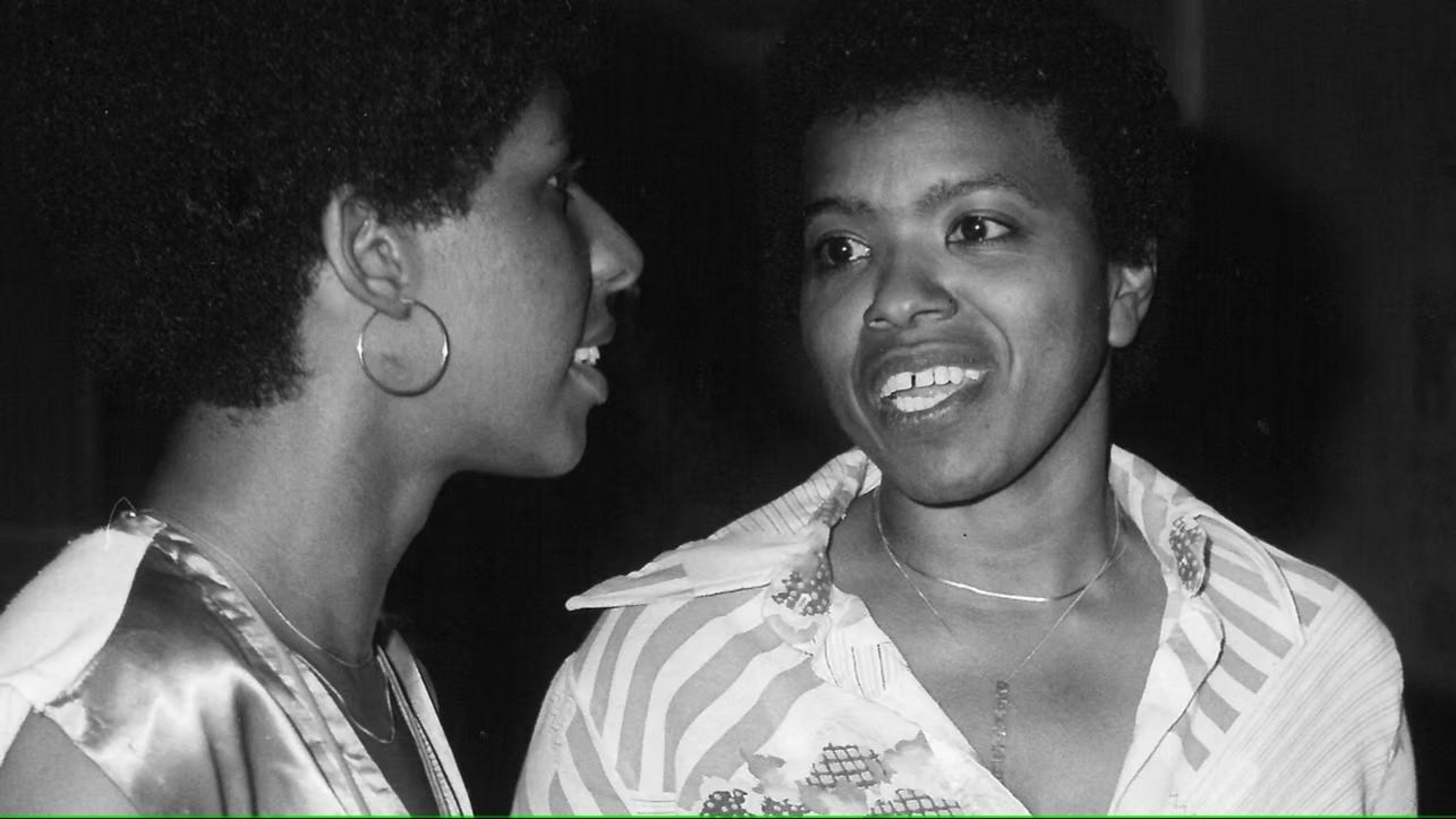

Honoring Jewel-Thais Williams (1939-2025)

We're sorry to say goodbye to Jewel Thais-Williams.

Jewel was born May 9, 1939 in Gary, Indiana.

She was the fifth of seven children, who grew up together in a three-bed, one-bedroom home. Her parents came from the outskirts of Memphis, Tennessee, and followed extended family to Gary, Indiana for a better life. Despite knowing nothing about the North, Jewel's parents sought to remove their children from the systemic racism of the South. In Indiana, Jewel and her siblings were able to attend public schools and receive a quality education. This would not have been possible in their rural Arkansas hometown.

Jewel's parents, inspired by some "pretty powerful ancestors," imparted upon her a determination to never give up.

"Dare to dream, no matter how impossible the dream is to achieve," said Jewel. "With patience and perseverance, you can accomplish anything you want. They surpassed those fears of 'what if?' and that's how we survived."

When Jewel was four years old, the family moved to San Diego, where her cousins were assigned during military service. When they first arrived, they shared a house with their cousins. There were a total of 23 people living in a two-bedroom house.

"We realized pretty quick that the Land of Plenty was not Indiana, but California," said Jewel. "California had plenty of everything!"

By age 9, Jewel was working at her family's grocery store. Her parents instilled a very strong work ethic in all their children. But Jewel thought she took it more seriously than others.

"My folks were just a couple generations removed from slavery," said Jewel. "The whole idea of working -- unless you were resting -- was what life was supposed to be all about. There was no such thing as leisure time. We got to play on Sunday afternoons, but it was either church, work, or school. Today, I'm grateful for that upbringing."

Jewel graduated high school in 1957. At the time, most California universities would only enroll one Black student at a time. Jewel's brother sought to attend University of California-Berkeley, but had to "sit out" for an entire year, waiting for the one Black student already enrolled to graduate.

After receiving a $50 scholarship from a black sorority, Jewel enrolled at UCLA.

"There were 27,000 students there, and less than 100 were African-American," said Jewel. "And there were more Africans than African-Americans."

Jewel called her sexual awakening "more of a waking nightmare." Her father was very religious and conservative, and didn't allow dancing, gambling, or even board games in the home. The children were not allowed to know about "worldly" things. Sexuality was simply never discussed.

"I saw very effeminate men, and very butch women, but there weren't a whole bunch of them," said Jewel. "You knew they were 'funny,' but that was pretty much it. They were different from everyone else, but we didn't realize this was something sexual. And I was always a tomboy, but that sure wasn't seen as anything, you know?"

"So I really didn't come out. I was drug out."

Jewel started seeing a co-worker in her mid-20s. One night, after drinking Scotch and listening to music, she asked Jewel if she'd ever kissed a woman.

"One thing led to another, and that was my first experience. We were together for the next 11 years."

After graduating UCLA with a history degree, Jewel was committed to owning her own business. The challenge was finding one that was recession-proof.

"My father said I should get a liquor store," laughed Jewel, "and I said, naw, that's too impersonal!"

In the late 1960s, Jewel worked across the street from the Diana Club. It had been a supper club, ballroom, and concert hall since the 1920s, when it was still on the western outskirts of Los Angeles. By the 1960s, it was most well-known for its racist and exclusionary treatment of Black customers.

"It was just terrible, the stories I'd hear," said Jewel. "And I told myself, you know what, someday I'm going to own that damn club, and everyone will be welcome."

But Jewel hadn't seriously considered opening a queer space. At the time, Black gay and lesbian bars were small, quiet, and often secretive places.

"They were drinking places. There were no dance clubs. The women had a place called Hi Dolly, which was a gentlemen's club that they rented out one night a week. It was in an unincorporated area, so you didn't get the police out there. But that was it. That's all we had."

As a Black woman, Jewel faced discrimination throughout her life. But it hurt the most when it came from her own community.

"If you were one of the browner people then, there were things that you couldn't do," she said. "And West Hollywood clubs wouldn't allow any people of color and no women."

Feeling unwelcome in LA clubs and excluded by white gay society, she decided to open a club of her own in 1973.

Jewel was the first Black woman in the United States to open a gay club -- and Catch One was one of the first Black discos in the nation.

After transforming the Diana Club into Catch One, Jewel openly welcomed ANYONE who wanted to dance -- even though same-sex dancing was still technically illegal.

“From its very inception, I wanted Catch One to be a place where everyone could come and feel welcome here, regardless if they were Black or white or Hispanic, straight or gay, whatever,” said Jewel. “I wanted a universal feeling of acceptance of everybody.”

"I knew it was going to be mostly Black gay folks," she said, "and for a long time, it seemed like I was the only one who had no problem with that. In those early years, Catch One was old white neighborhood folks by day, straight blue-collar African-American men by night, and then the gays would come out to dance!"

"For four or five years, the customers called me Diana. They thought it was my name, even after this wasn't the Diana Club anymore. It was okay with me. I had no problem with that."

But nothing about Catch One was simple or stress-free.

First, she was denied small business loans from the agencies that existed to support her.

"I had $1,000 when I came in here," said Jewel, "and I had no idea where the rest of the money was going to come from. I had 30 days to find it, and I stretched that to 60 days. I never once thought I wouldn't be successful. And you know what? That money came in right on time."

She couldn't even tend bar herself -- as California law forbid women from being bartenders -- and a lot of people wouldn't work for a Black woman. And she struggled to find customers willing to support a Black female bar owner, much less spend their money in a diverse neighborhood far away from white West Hollywood.

"The Hollywood paparazzi was just NOT coming down to Pico and Crenshaw," laughed Jewel.

When people did show up, they were often scared away by the police cars that would park outside just to intimidate customers and storm the bar looking for imaginary "violations."

Nobody expected Catch One to succeed. All the odds were against it.

And, yet, it became the longest-running Black gay club in Los Angeles.

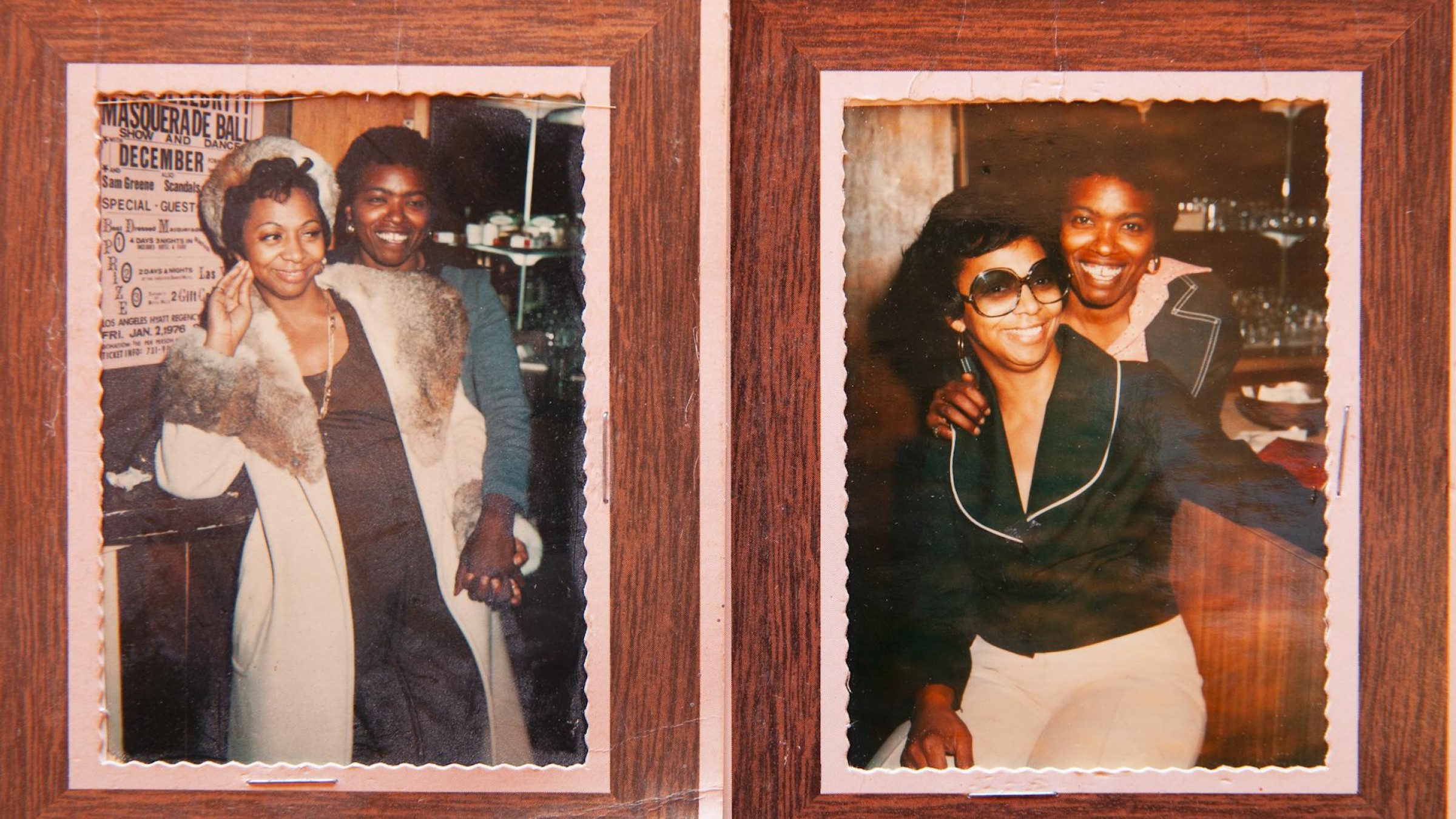

Catch One became a destination for celebrities from Sylvester to Donna Summer to Rick James to Madonna to Whitney Houston to Etta James. Stars loved that cameras weren't allowed in the club -- a rule that stayed in place until 2010 -- so they could cut loose just like everyone else.

Many considered it the Studio 54 of the West Coast -- but it was more than that. It was a Studio 54 that let everyone in. And it elevated Black community, culture, and experience to a whole new level.

"Communities -- black and white -- were pretty separate for a long, long time," said Jewel. "We were able to introduce the clientele to things we, as Black people, just didn't know about or have access to."

For example, Catch One was the first Black gay club represented in the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade.

In 1982, Jewel opened a second Catch One in Houston. She'd planned to open five Catch Ones -- Houston, Denver, Oklahoma City, Albuquerque, maybe Phoenix -- but only Houston ever happened. The bar closed in late 1984 just as AIDS was beginning to take a toll on gay nightlife.

Over the years, Jewel was very cautious not to incur debt. She'd been through that stress when she opened the club, and she wasn't going to live with it again. She always believed in creative financing versus what she called "hard money" loans. And, underneath it all, she was determined to win.

"Someone told me I was hanging onto a plantation mentality," said Jewel. "That because I thought I was poor and acted like I was poor, I would stay poor for the rest of my life. But I never felt the need to have more than I needed. I never felt the need to spend more than I had."

And she invested her profits back into the community she came to love.

Despite criticism from Black churches, Jewel was a champion for people with HIV/AIDS. She served on the Board of Directors for the AIDS Project of Los Angeles, co-founded the Minority AIDS Project, and founded Rue's House (a home for mothers with AIDS and their children.) She leveraged the club's popularity and platform to raise countless dollars for HIV/AIDS care close to home.

While the prejudice became less visible over the years, it didn't exactly go away. For example, when an arsonist nearly destroyed the bar in 1985, the LA Fire Department never even came to investigate.

"They wanted me out," said Jewel. "It's like a black gay club in the 80s....forget it. Nobody wanted me there."

Catch One was the subject of not one, but two documentaries -- one of which Jewel traveled to Milwaukee to introduce at the UWM Union Cinema. She received numerous awards, including the Dream of Los Angeles Award in 2012, and served as the Grand Marshall of the LA Pride Parade in 2016. In 2019, the intersection of Pico and Norton was renamed Jewel Thais-Williams Square in her honor.

"Right before Ella Fitzgerald passed, she came to see the place again," said Jewel, explaining Fitzgerald performed at the Diana Club in her youth.

"She was telling me how it was for her, how she used to have to go up the back steps... she couldn't go through the front door or socialize with anyone. That might offend the white patrons."

After pursuing a master's degree in medicine, Jewel embarked on a side career in holistic health. She traveled to China to study safe alternative medicines. She opened the Village Health Foundation, a non-profit, pay-what-you-can clinic and community center, in 2001.

"So many of the illnesses African-Americans get are preventable. But instead of helping us with prevention education, the medical profession treats us with pills and cuts us open," said Jewel.

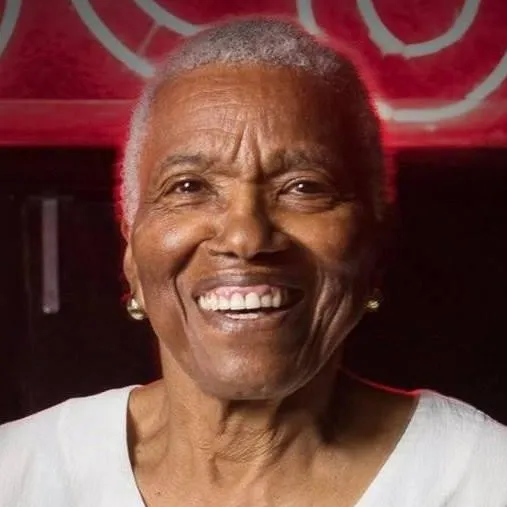

After 42 years, Jewel sold Catch One to focus on her newfound passion.

"I always had that in my soul: I will go when I get ready to go, and not before," said Jewel.

Jewel and her wife, Rue, were together for nearly 40 years. They met at Unity Fellowship Church in Santa Monica.

"I asked her if she wanted to spend the night so she wouldn't have to drive four hours home," said Jewel. "I said I'd sleep on the couch. Needless to say, I didn't sleep on the couch. That was kind of our first unofficial date."

While buying a house in Lake Arrowhead in 1997, the couple was shocked to encounter midcentury racism alive and well. The deed to the property clearly stated that the property could not be sold to any Black people, nor could they inherit it from anyone else.

Jewel overcame every single challenge life ever threw at her. And yet, she never lost her commitment to self-care, well-being, and acceptance.

"My advice? Look in the mirror every day, and say I love you just as you are. In the end, you're all you've got."

Questions? Contact us.

Read More