Mike Vaughn: spinning the soundtrack of gay liberation

"I thought to myself, you're not in Wisconsin any more, little boy. This is heavy-duty stuff."

In the frigid winter of 1973, Mike Vaughn was a pre-med student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a 3.9 GPA and a future that felt prewritten. But on New Year’s Eve, he found himself pacing South Park Street, circling the block twenty times before he could find the nerve to enter a very specific nightclub.

“I was walking into a gay bar for the first time,” said Mike, “and I was certain everyone in town was watching me.”

Fortunately, Mike wasn’t alone. He was with his younger brother, home on military leave for the holidays, who’d been going to the bar since he was underage.

That night, as they stepped into the Back Door, they weren't just entering any old Wisconsin tavern. They were walking into a new world.

The air was thick with the "glitter era"— androgynous fashions, platform shoes, and the sweeping, orchestral strings of the Love Unlimited Orchestra’s "Love’s Theme."

“That was the first thing I heard when I walked in there on New Year’s Eve,” said Mike, “and I will never forget that moment.”

For Mike Vaughn, that night was the first drumbeat in a lifelong anthem that led him from the earliest gay nightclubs of the Midwest to the birthplace of gay liberation in Greenwich Village.

Gay life in Madison was a game of chance before the Back Door.

“You would hear about these places where gay people went,” said Mike, “but it wasn’t great. We were only tolerated by the straight owners and customers. We weren’t truly invited, welcome, or accepted. We were tolerated, as long as we spent money. You didn’t feel great about these places, because they didn’t really make you feel great about yourself.”

Madison’s most popular spaces had been the 602 Club and Kollege Klub (known as the KK,) among several bars listed in the mail order gay guides of the 1960s and 1970s.

“On Friday and Saturday nights, frat boys would drop off their girlfriends at the sorority houses and head to the ‘Gay K’ to cruise each other in the corners,” said Mike. “These places were just throbbing with sexual energy that went nowhere. I never picked up anyone at either place, but it was such a strange thing to witness.”

By 1971, things had started to change.

Mike remembers the Pirate Ship, which featured low-lit ambience, a wood-masted schooner-shaped bar, and "Patty," a legendary bartender who ran the room with an iron fist. The Pirate Ship had been around for quite a while, but as more and more gay customers showed up, it became more of a queer space.

“Patty was visually impaired," said Mike. “But she did not miss a thing that happened in the Pirate Ship. She really watched out for people. If she thought someone was a hustler, she would not serve them.”

“It was very closeted. No dancing, no kissing, not even hugging. Just a lot of eyeballing each other from a safe distance.”

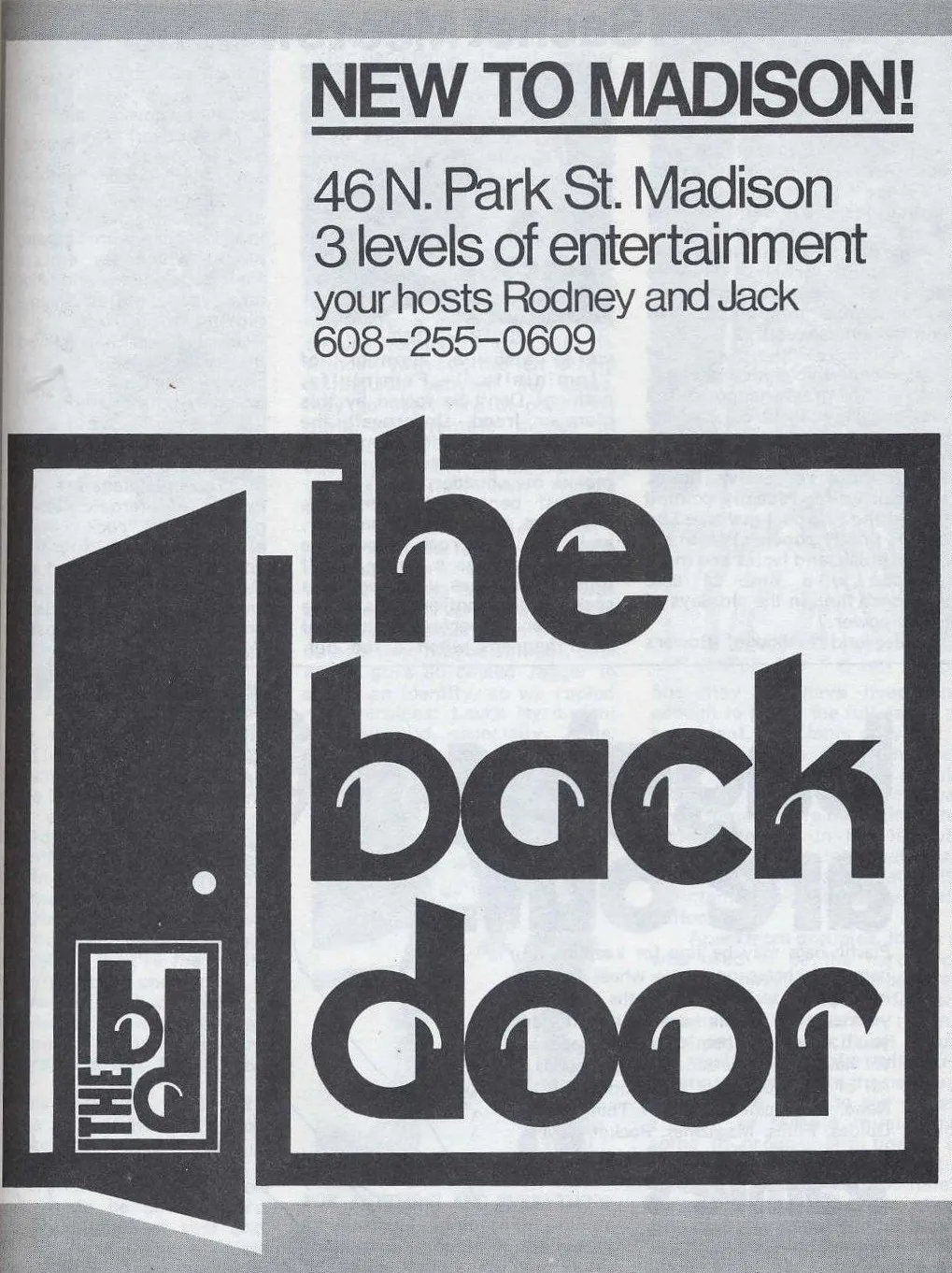

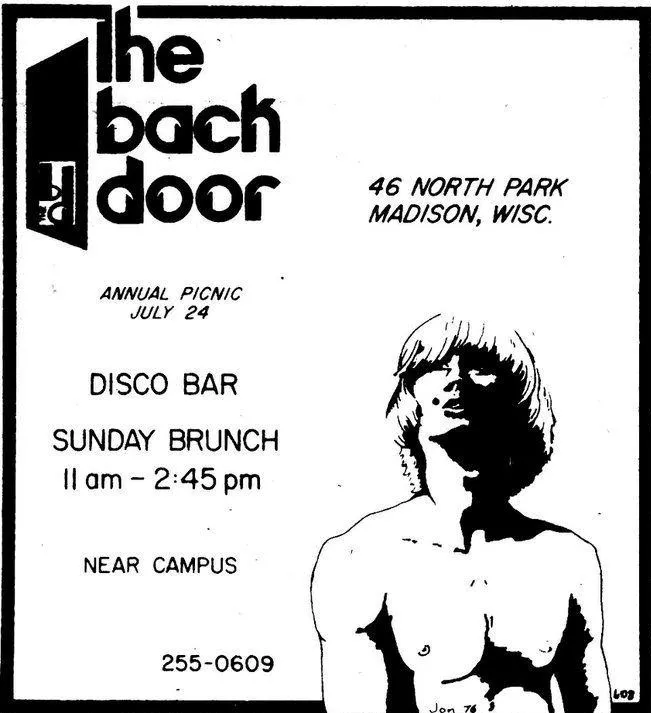

The Back Door changed the landscape. Founded by Rodney Scheel and Jack Faust, it propelled the community right out of the shadows. It was the first gay bar in Madison with a dance floor where men or women could safely dance together. In earlier queer spaces, dancing – of any kind – was strictly forbidden.

“I remember walking in that doorway and going down the stairs into the basement,” said Mike. “There were bench seatings along one wall, a pool tables, and a small bar. There was a kitchen downstairs where they served burgers and Sunday brunches. And then you’d go up the stairs to the big dance floor, where the magic happened.”

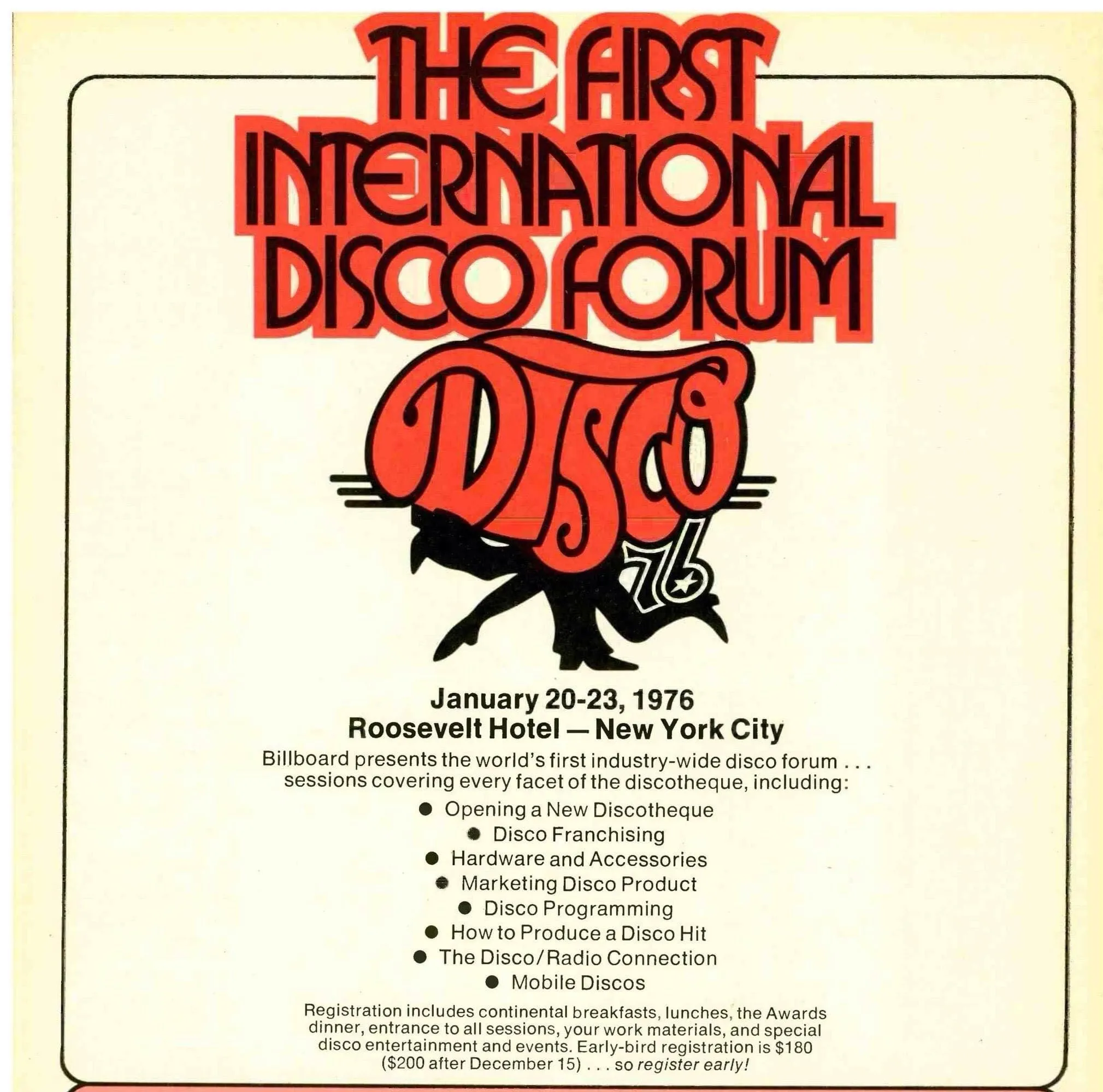

The 12-inch single was becoming the industry standard. At the Forum, Mike watched Claudja Barry, Andrea True, and The Trammps perform in ballrooms, realizing that the music he was playing in Madison was part of a global movement.

“I saw DJs mixing records for the first time, really mixing two records together to sound like one,” said Mike. “I met all the record company promotion people, all the vendors, all the performers, in a very small and select hotel ballroom."

"It was a life-changing experience in a very intimate space.”

Making it in Rockford: 7th Heaven

After returning home, Mike was recruited by Jack Faust to help him open 7th Heaven (528 7th St.,) the first openly gay bar in Rockford, Illinois.

“I’d only been to Rockford once before this,” said Mike. “I went down to visit him for the weekend, and we visited the Office Tap on State Street. It was not the kind of place you entered through the front door. You entered through an alleyway. It was owned by very, very strict people who were begrudgingly running this gay bar. They weren’t fond of their gay customers at all.”

“Jack bought a bar with a reputation for being a ‘hillbilly bar,’” said Mike. “I relocated to Rockford around Thanksgiving 1976 and we aimed for a December opening. We had to close the bar for two weeks to lose the previous clientele. 7th Heaven was an immediate success: the people of Rockford were very, very excited about it, because, again, it was the first place with a dance floor where gay people could dance together.”

As the bar manager and DJ, Mike traveled to Chicago frequently to support the bar. He joined a "record pool," a collective of DJs who received promotional 12-inch singles and albums directly from labels. He became a conduit, bringing the sounds of the New York underground to Seventh Heaven (and later, Milwaukee and Madison.)

However, Mike wasn’t a huge fan of Rockford. The city was still dry on Sundays, meaning that alcohol could not be served or sold anywhere but restaurants. And the city was still very, very conservative: very few customers would enter through the front door in 1977, fearing they might be seen.

“It wasn’t a place I wanted to stay for very long,” said Mike.

In spring 1980, Jack Faust tried to relocate 7th Heaven to the former Knights of Columbus Hall at 114 N. Winnebago St., but the permit committee unanimously denied him twice (first in February and again in May.) He accused the City Council of anti-gay discrimination, which seems likely as the Rockford Register-Star was quick to name 7th Heaven "a local bar frequented by homosexuals." Unable to relocate, it seems 7th Heaven closed sometime within the next year.

In August 1981, Mike decided to call it quits. His banking career was becoming more important to him, and the pace of nightlife work vs. daylight work was increasingly challenging. He had one last big night at The Factory and officially retired.

“I made mixtapes for Si Smits to play at Boot Camp, I spun at the MAGIC Picnics, the patio at Rod's Bar in the Hotel Washington, and guest spots here and there,” said Mike. “But after seven long years, I was just not interested in being a resident DJ anymore. I did keep my vinyl record collection current though."

He still hung out at happy hours, including This Is It, which attracted a more mature, professional crowd at the time. Mike likens it to New York’s Townhouse Bar, where sophisticated customers showed up at 5pm for cocktails in suits and ties.

In 1990, Mike moved into one of the first residential apartments in the Historic Third Ward, which was rapidly losing its earlier edginess. While the Factory was long gone, the M&M Club and Wreck Room were within walking distance.

“Before I left Milwaukee in the 90s, George welcomed me back to spin old disco in the front bar at La Cage,"said Mike. “It’s funny because I already felt too old for La Cage by that time.”

Making it in Manhattan

After seventeen years in banking technologies, Mike took a position with Citibank and moved to New York City in 1996.

“It took me 20 years,” said Mike, “but I finally made good on my promise to move to New York. And the best part was that it was a corporate relocation, so someone else paid my moving bill.”

In April 1996, he met his husband Ed Baskiewicz at the Townhouse Bar. Ed and Mike married in Massachusettes in 2009, when New York State was recognizing out-of-state same-sex marriages prior to national marriage equality in 2015.

Today, Mike lives in the Murray Hill neighborhood, two blocks away from his first apartment in the city, which he can see from his front room window. He’s very active with the SAGE Men's Discussion Group, which meets twice a month. During the off weeks, several members meet for happy hour at Julius' (one of the oldest gay bars in the nation.)

The New York of 2026 is vastly different from the city Mike first fell in love with. In 1976, the "back door" of a bar was the only way to meet. In 2026, apps have made hooking up a high-speed exchange, while the physical gay bar has become a second choice rather than a necessity.

The West Village of 1976 was affordable and accessible. In 2026, it has become a real estate playground for the global elite. Although landmarks like Monster, Stonewall, Duplex and Ty’s remain, the queer community has scattered into Brooklyn and Queens, turning neighborhoods like Bushwick and Astoria into the new gayborhoods. Hell’s Kitchen is the new Manhattan hotspot, filled with gay bars, restaurants, and stores like Christopher Street and 8th Avenue used to be.

While 2026 offers legal protections Mike couldn't have imagined in 1973 (marriage equality, non-discrimination laws), some of his peers lament the loss of the "secret world” they once called their own. The codes of yesteryear are no longer needed for survival.

“I kept my 20-odd cases of vinyl records for decades, hauling them around from home to home, until they found their final resting place in a NYC storage locker,” said Mike. “After a health crisis in 2015, I thought, what in the hell is my husband going to do with all this stuff? He’s going to call 1-800-GOT-JUNK! And that would kill me all over again.”

One day, Mike got a call from Joe Miller, a fellow DJ in Madison, Wisconsin, looking for a certain record.

“On a whim, I just straight out asked him: ‘would you like my records? This stuff is sitting in a storage locker and I’m not using it.’ He got a van, came out to NYC one weekend, and emptied out the storage locker. He took the vinyl, turntables, mixer, CD burner, everything,

and took it back to Wisconsin where he’s still using it now.”

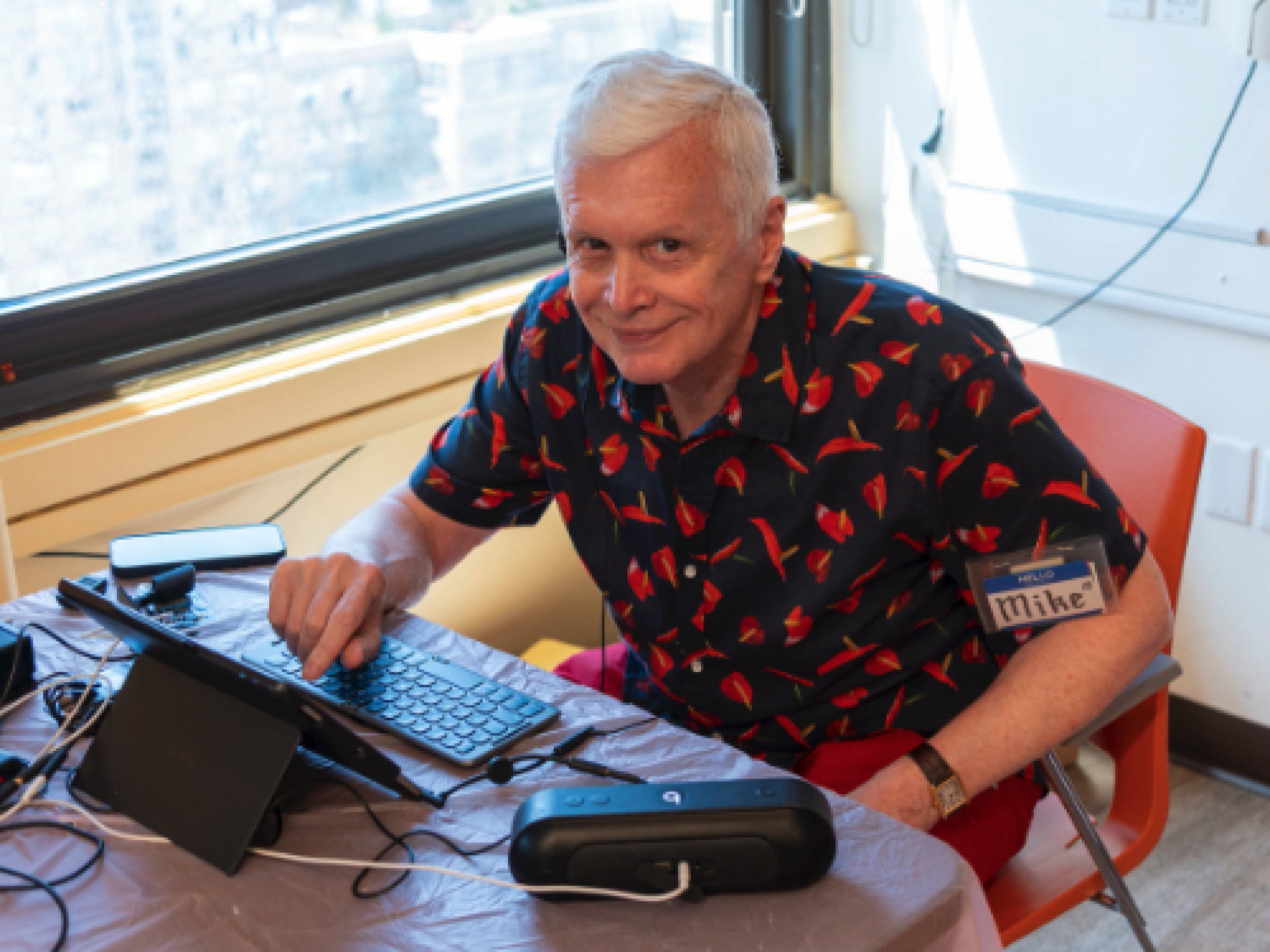

“And then, believe it or not, the opportunity to DJ at a SAGE event came up!”

Mike added a DJ app to his iPad, downloaded all his favorite vinyl tracks from the internet, and remixed them all over again. He spins for his SAGE group every other month at the Edie Windsor SAFE Center in Manhattan and the Queens Center for Gay Seniors.

“I’ve even got my own Soundcloud page now. The Boot Camp tapes are posted, along with my mixes from 2017 on."

The music never stops

Now in his 70s, Mike hasn’t slowed down for a moment. In 2019, he retired from Citibank, where he was a senior vice president. He and Ed have major travel plans for 2026: Mike's 37th Mardi Gras in New Orleans, a week in Italy followed by an adventurous Mediterranean cruise, and maybe even a Pride Month visit to Milwaukee.

More than anything, Mike is grateful that he was born and raised in Madison.

“Madison was a very liberating place to grow up,” he said. “I’d be a very different person if I was born and raised anywhere else, including Milwaukee.”

He’s grateful for the experiences he’s had since 1976, including viewing the AIDS Quilt in 1989 and attending Stonewall25 in 1994. He’s also grateful for his long-term friendship with Eldon Murray, who was his stockbroker, and Bob Stockie, who was his partner for 10 years and also the cover artist for GPU News.

“Eldon founded SAGE Milwaukee based on the New York City model, and I was on the first board of SAGE Milwaukee with him,” said Mike. "SAGE Milwaukee was the first SAFE affiliate outside of New York City. He really molded me as a person in the business world, where it wasn’t always so safe to be openly gay.”

“Eldon once told me, 'I could screw sheep in the middle of Wisconsin Avenue, and my customers won’t care as long as I keep making them money.’ He encouraged me to be an authentic person in the workplace and never to apologize for who I was.”

Mike Vaughn didn't just witness Wisconsin LGBTQ history: he spun the soundtrack for it.

When he hears a certain track, he isn't a man in his 70s in Manhattan; he’s a 21-year-old at the Back Door, watching the glitter kids go wild for Bowie, Iggy, and the New York Dolls.

"I’ve had a pretty interesting life," Mike reflects. “And I lived my life as one big old extended remix.”

Mike at the Hotel Washington

Mike at the Hotel Washington

Mike at Mardi Gras

Mike at Mardi Gras

Mike and Ed

Mike and Ed

Mike and Ed

Mike and Ed

Mike and Leon Wagner

Mike and Leon Wagner

Mike and Joe Miller

Mike and Joe Miller

Mike DJing at the Edie Windsor Community Center

Mike DJing at the Edie Windsor Community Center

Mike and friend in Belize

Mike and friend in Belize

recent blog posts

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 10, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.