"Packer" Chad Bowman: from Two-Spirit roots to Milwaukee's rainbow

"When Goldie Adams says, 'follow me, kid," you do what you're told!"

"Always stand up for who you are and advocate for your rights and the rights of your community. Get involved and help others."

These wise words come from Chad Bowman, also known as "Packer Chad," a longtime mover and shaker in the LGBTQ scene of his birthplace, Milwaukee.

Chad always knew he was different, but it was in eighth grade that he realized he was gay.

He has Native American heritage from the Stockbridge Munsee band of Mohicans, with ancestors hailing from upstate New York, which has always influenced his understanding of himself and others.

"In my culture, we refer to ourselves as 'Two-Spirits,' embodying both masculine and feminine energies. I've been fortunate to be fully accepted by my family and friends in the tribe."

"Today, performers often clash, with everyone wanting to take the lead role, in contrast to the past when they collaborated to create spectacular shows. I miss those times."

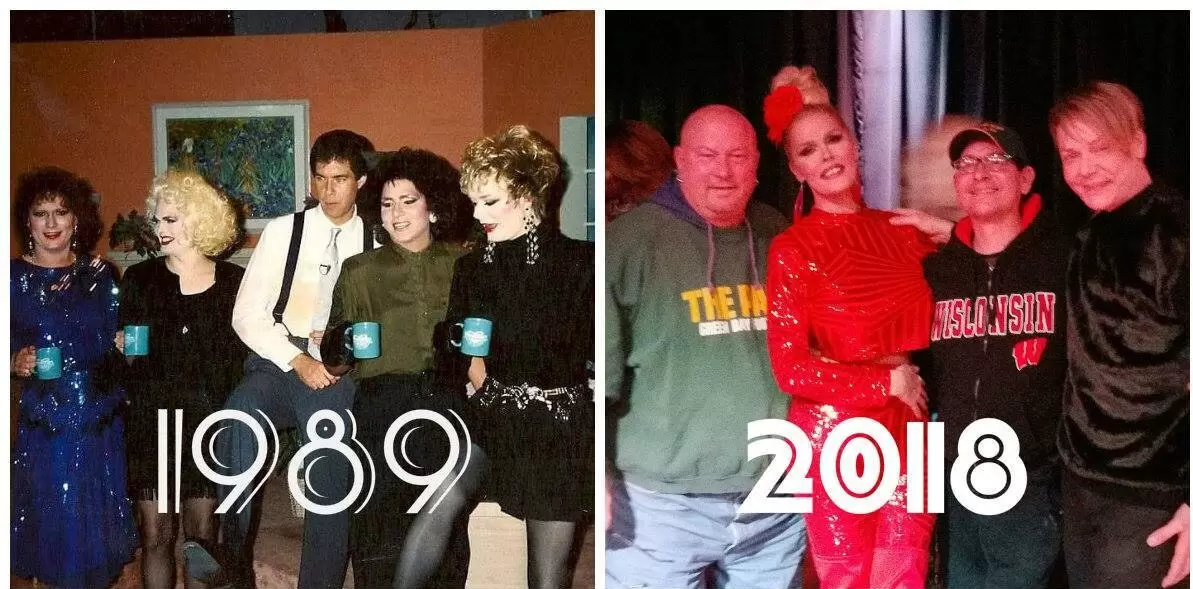

One of his favorite drag elders, campy queen Ronnie Marks (RIP), epitomized this type of comedy and significantly influenced his Chastity Belt character. Appearing on the WISN-TV Channel 12 show "Milwaukee's Talking" with drag superstar Rona (Ron Thaite,) alongside the talents of Mimi Marks and Miss B.J. Daniels is one of his fondest memories.

Chad notes that drag has transformed into a more cabaret style over the years, moving away from traditional "female impersonation." While he acknowledges that the younger generation is incredibly creative and brings amazing costumes, he also feels that the overkill of drag has taken a toll.

"Once you've seen one drag performance, you've seen them all today. The classic performers from the golden era of drag had more distinct styles and images, in my opinion."

His past reveals a well-lived life that included performing in drag shows, playing softball with the gay softball league, and socializing at many LGBTQ bars that flourished in Milwaukee during his youth. The yearly ritual of getting dressed up for the Mr. and Miss Gay Wisconsin "Pageant" at the Marc Plaza was an annual highlight for him until the contest ended its decades-old run.

"I also cherished participating in fundraising events like 'Possum Queen' for ARCW and MAPFEST."

You may have seen him marching in the Milwaukee Pride Parade recently, donning his version of Two-Spirit symbolism reflected in his heritage. You can't miss him in these colorful costumes.

"I miss the camaraderie we had in our community; we were incredibly tight knit." he laments.

Chad Bowman attended Milwaukee Tech, MATC, and Truman College, where he studied Communications.

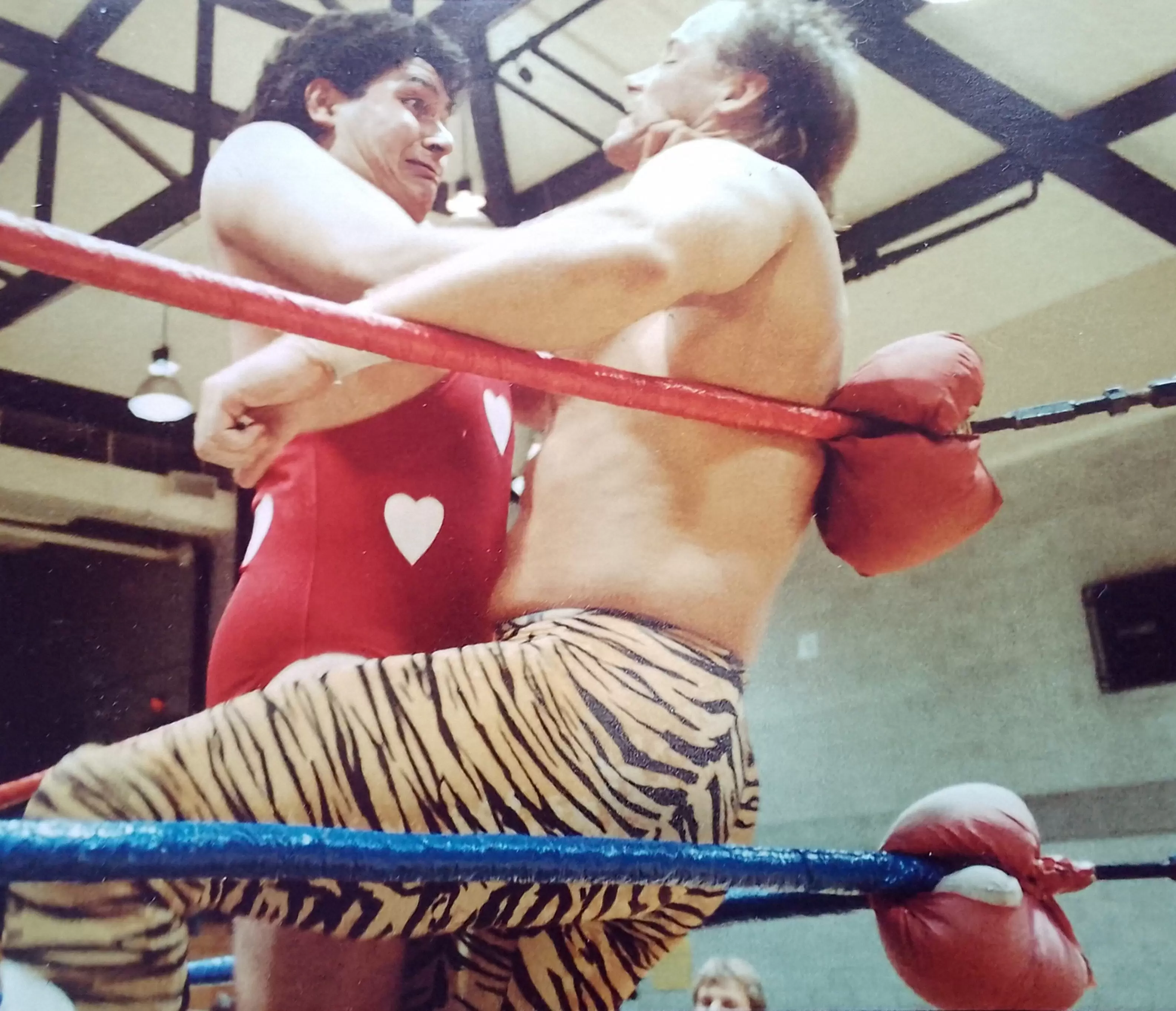

He works in the service industry and has a background in professional wrestling.

He also raises money for local charities at Clementine's Tavern, where he bartends, and other venues.

Chad's appearance on "Milwaukee's Talking" -- and the cast reunion 30 years later

Chad's appearance on "Milwaukee's Talking" -- and the cast reunion 30 years later

Chad and friends

Chad and friends

Chad and friends

Chad and friends

recent blog posts

January 17, 2026 | Garth Zimmermann

January 16, 2026 | Michail Takach

January 10, 2026 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.